Visual Arts Commentary: John Singer Sargent — A Particular Sort of Loner

By Trevor Fairbrother

Viewing John Singer Sargent and his art through the lens of identity studies and LGBTQ history supplies new insights into claims about his homosexuality.

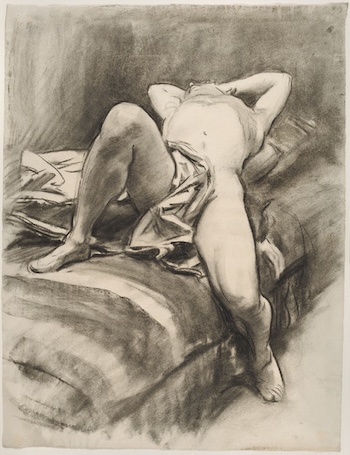

Charcoal drawing in Sargent’s album of figure studies: Reclining Male Nude, Draped (c. 1900; Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond)

This essay explores posthumous attitudes toward the bachelor status of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), the American portraitist who made London his home base in 1886. Collateral descendants have long maintained that there are no known written materials proving that he engaged in sexual pursuits of any sort. Stanley Olson, who wrote an authorized biography in 1986, portrayed him as a workaholic and a “full-blown enigma.” He declared, “No one who knew him well or slightly has ever been tempted to suggest anything whatever about his private life, which presents a major obstacle for any claim [of concealed homosexuality] which is advanced.” As will be seen, Olson was wrong.

Four decades later, viewing Sargent and his art through the lens of identity studies and LGBTQ history offers hope of new insights. Those terms did not exist in his lifetime, but same-sex relationships did, and professionals like him jockeyed their public and private lives to accommodate them. Polite society in Sargent’s day was wary of close attachments between men and urged matrimony as an advantageous imperative, even when it was a marriage of convenience. His career was thriving in 1895, the year Oscar Wilde – his married neighbor on Tite Street – was convicted of “gross indecency” and jailed. Before and after that scandalous trial, Sargent maintained a spotless public reputation and was never short of portrait commissions. He left his estate to his sisters: Emily, who remained unmarried, and Violet, Mrs. Francis Ormond, who was the mother of six children.

On April 16, 1925, the New York Times published an item titled “J. S. Sargent Dies in Sleep in London.” It said: “He never married. He was a secluded and inscrutable personality. He never made speeches, he never wrote criticisms and he never gave interviews for publication.” It was followed on April 19 by a longer appreciation that ended: “John Sargent was a bachelor. … He was very fond of music, played the piano and was a confirmed concertgoer.” In 1926 Percy Grainger, the piano prodigy and composer, wrote a short appreciation in which he warmly commended Sargent’s “inscrutability in all that touched his purely personal life.” (Grainger understood discretion, for he pursued masochism with female partners.)

Sargent’s long reign as an establishment figure merited grand memorial exhibitions in Boston, New York, and London. His demise inspired broadsides from modernist partisans. Roger Fry argued that Sargent was not an artist, but rather a “striking and undistinguished” illustrator; moreover, he dubbed the best early works feeble, rather vulgar echoes of Édouard Manet and the Impressionists. (Transformations, 1927.) The American Lewis Mumford claimed that bravura brushwork and a “dashing eye for effect” ultimately failed to hide “the essential emptiness of Sargent’s mind.” (Lewis Mumford’s The Brown Decades: A Study of the Arts of America, 1865-1895, 1931.) Unsurprisingly, Sargent’s art crashed in the art market for several decades.

In 1955, Charles Merrill Mount, a young American painter, hoped to change things with his book John Singer Sargent: A Biography. He repudiated Roger Fry’s criticisms and unexpectedly insisted that Sargent was heterosexual: “His single state remained a puzzle. He was a large and strong man, with, if one knew him at all, enough indications of virility not to be taken for an example of the intellectualized homosexuality notable among artists in London. … The young musicians who trailed him everywhere were thought effeminate. He had some strange friends, some of whom appeared to have relationships among themselves of which society, though aware of in an oblique way, did not openly approve. [He had] none of the petty preciousness displayed among oversophisticated intellects.” Most reviewers deemed Mount’s claims overly admiring. William Gaunt, writing for the Times Literary Supplement, argued that Sargent’s best portraits were very fine, but, overall, he was “an accomplished executant rather than a great creative artist.”

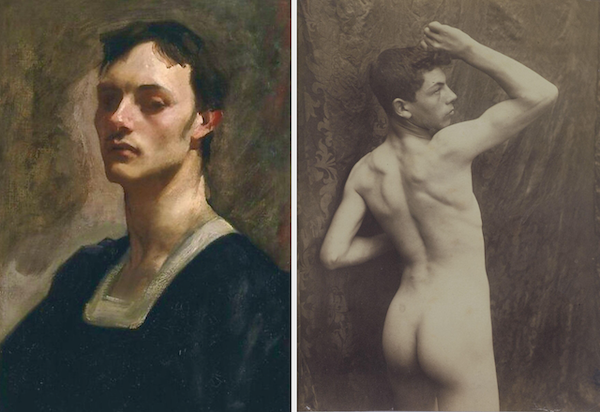

Two works that Sargent owned. Left: Sargent, Albert de Belleroche (c. 1883; private collection). Right: Vincenzo Galdi, untitled photograph (1890s; Victoria & Albert Museum). Photo pairing by author.

In 1965, Richard Ormond, Sargent’s great-nephew, characterized his kinsman as “reserved and austere.” Writing for The Saturday Book, the 26-year-old Englishman explained, “[Sargent] was only at ease with his family and close friends, detesting social occasions and the flattery of the fashionable world. His life was dedicated to his art, and his apparently mysterious private life held no secrets beyond his easel and his paint brush.” Ormond was a museum curator in Birmingham, where, in 1964, he organized a Sargent exhibition with about 100 works, a third of which belonged to his relatives. By 1967 he was working at the National Portrait Gallery, London. In 1979 he and James Lomax co-curated the first large international loan exhibition: John Singer Sargent and the Edwardian Age opened in Leeds and traveled to London and Detroit. The accompanying catalogue omitted the fact that Sargent never married, but mentioned supposed gossip about a “romance” with his friend Flora Priestley in the 1880s. Hilton Kramer’s review in the New York Times gave a sense that the tide was turning: “Although it is certainly no longer tenable to regard Sargent as a great master, it seems to me undeniable that he was a painter of uncommon gifts. … Sargent was never deep, to be sure, but he had a certain power, all the same.”

In 1981 Arts Magazine published an essay by me on Sargent’s large charcoal drawings of nude and partially draped male models, collected in an album that Violet Ormond donated to Harvard University in 1937. The piece argued that the radiance and bravura of these works manifested the pleasure the artist took in observing and depicting the manliness of subjects from London’s Italian enclave. I also drew comparisons with the earthy homoerotic beauty captured contemporaneously by photographers Guglielmo Plüschow and Vincenzo Galdi. The article had no immediate impact apart from a few private expressions of wariness and disapproval. (Decades later I learned from a 2015 online report that a male nude by Galdi, formerly owned by Sargent, was in the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection: in 1925 the artist’s sisters donated over 600 photographs from his estate; the Sargent connection fell from sight after the pictures were dispersed within the museum’s reference library.)

In October 1986 I escorted Andy Warhol and his assistant Benjamin Liu through the galleries of the Whitney Museum’s Sargent retrospective and recorded the conversation. The artist played the naïf and started a pattern of camp back-and-forth. Arts Magazine published the interview the following February. In this excerpt, we are looking at a charcoal portrait of Mrs. Charles Hunter and I am suggesting that my peers live in denial about Sargent’s bachelor status.:

AW: Is this Mrs. Sargent?

TF: No.

AW: Was there a Mrs. Sargent?

TF: No. He didn’t marry – like Henry James.

AW: There wasn’t a Mrs. James?

TF: No. Are you surprised?

AW: Yeah, I’m surprised. Well, tell me all the stuff – you mean there’s a big story to his life?

TF: No, we don’t know.

AW: You don’t know? You know everything.

TF: The scholars don’t know. What do you think?

AW: Well I don’t know.

TF: Can you tell?

AW: You mean nobody talks about him?

TF: I guess not.

AW: Really? Not one person? There must be a story, you just don’t want to tell it to us.

TF: Scholars aren’t supposed to …

AW: dwell …?

In 1994 I wrote a monograph on Sargent for the Library of American Art series (Harry N. Abrams). In a review for Art History (March 1995), the art historian Kathy Adler wrote: “Fairbrother considers Sargent’s homosexuality, and the homoeroticism of many of his drawings, including drawings of the male nude serving as preparation for subsequent paintings of female figures. His brief but telling analysis of Sargent’s drawings of the African-American Thomas E. McKeller is particularly interesting.” Four years later, Richard Ormond dismissed and discouraged the discussion of Sargent’s sexuality:

The record is not clear. … That he was a physical and sensual kind of person is clear from the whole tenor of his work. But he did not relish intimacy, and he avoided emotional entanglements likely to complicate his life and compromise his independence. If he had sexual relationships, they must have been of a brief and transient nature, and they have left no trace. The answer is that we simply do not know, and decoding messages from his work is no substitute for evidence.

The statement appeared in the catalogue for the landmark exhibition John Singer Sargent, which opened at London’s Tate Gallery in 1998, then traveled to Washington, D.C., and Boston.

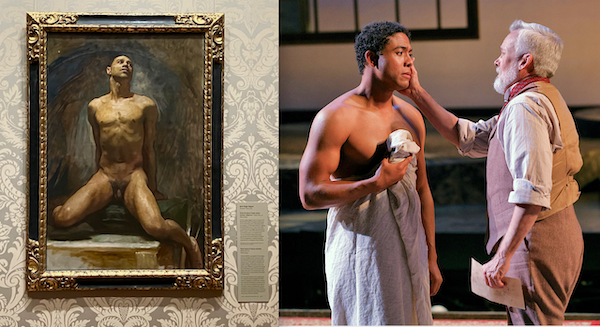

Detail of a charcoal study for the mural Atlas and the Hesperides (1921–25; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). Thomas E. McKeller modeled for the figure of Atlas.

In 1999 Norman Kleeblatt curated the exhibition John Singer Sargent: Portraits of the Wertheimer Family for the Jewish Museum, New York. The catalogue included my essay titled “The Complications of Being Sargent.” It quoted a letter written by the art critic Clive Bell in 1927 in which he described a luncheon at which the French portraitist Jacques-Émile Blanche insisted that Sargent had been “notorious” in Paris and Venice for his homosexual exploits. Sargent painted Blanche in the late 1880s and they remained in professional contact; moreover, Blanche was a closeted homosexual who married a childhood friend five months after Wilde was jailed. In the same 1927 letter, Bell noted that Sargent’s “sexual life” was widely discussed by his friends in the so-called Bloomsbury set.

In 2000 I organized a project at the Seattle Art Museum titled John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist. It made the Wertheimer Family show the centerpiece of an idiosyncratic survey of the artist’s work. One section presented all the drawings from the album of male figure studies acquired by Harvard in 1937 in concert with the painting Nude Study of Thomas E. McKeller (1917-20, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). The artist and writer Jonathan Weinberg made this observation: “[I congratulate Fairbrother for] changing the terms of Sargent scholarship [and] forcing people to deal with the implications of sexuality. [His Seattle show] is courageous, growing out of years of work that was resisted.” (Weinberg, quoted by Patricia Failing in her article “The Hidden Sargent,” Artnews, May 2001.)

Much like leading museums at this time, commerce-driven Hollywood was leery about same-sex attraction. “Brokeback Mountain,” Annie Proulx’s short story about a Wyoming ranch hand and a rodeo cowboy, debuted in The New Yorker in 1997. Nonetheless, the writer had doubts when two colleagues promptly requested to option it for a film: “I simply did not think this story could be a film: it was too sexually explicit for presumed mainstream tastes, the general topic of homophobia was a hot potato unless gingerly skirted, and, given Hollywood actors’ reluctance to play gay men (though many gay men have brilliantly played straight guys) it would likely be difficult to find a good cast, not to say a director.” Proulx made those comments after Ang Lee’s film Brokeback Mountain premiered at the 2005 Venice International Film Festival and won the Golden Lion Award for best picture. (Annie Proulx, Larry McMurtry, and Diana Ossana, Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay, 2005.)

In 2015 the writer Colm Tóibín wrote an article titled “The Secret Life of John Singer Sargent” for the Daily Telegraph. He championed my reading of Sargent’s drawings of male nudes, which he described as “openly erotic.” After stating that a “masked sensuality” and an “aura of performance” are aspects of Sargent’s personality as an artist, Tóibín suggested that an openness to the homosexual undercurrent in the work might “encourage us to look at the paintings … more subtly and carefully, and indeed may allow the work itself to yield much more.”

Left: Sargent’s McKeller on view at the MFA, Boston, 2025. Right: McKeller and Sargent portrayed by singers in American Apollo, Des Moines Metro Opera, 2024. Photo pairing by author.

Paul Fisher entered the fray in 2022 with The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World. He synthesized much from the Sargent literature and suggested correspondences with such trending academic topics as gender nonconformity, global commerce, ethnicity, and race. A professor of American Studies, Fisher eschewed the terms “homosexual” and “gay” to prevent queer studies practitioners from dismissing his argument as ahistorical. When reviewing the book for The Gay and Lesbian Review, novelist Andrew Holleran advised readers that Fisher’s circumspection grows frustrating: “It’s as if the whole book is written in gaydar. There is no evidence, but much guilt by association.”

Stage performances are the only tangible representations of Sargent as a homosexual. In 2016 The Royal Ballet, London, debuted Strapless (choreography by Christopher Wheeldon; score by Mark-Anthony Turnage). One of the characters was Albert de Belleroche, a young art student in Paris, who is presented as Sargent’s paramour. In 2024 , the Des Moines Metro Opera debuted American Apollo (music by Damian Geter; libretto by Lila Palmer). The plot imagined Sargent having an affair with Thomas E. McKeller, an African American “bellman” at Boston’s Hotel Vendome, which caused a split-up with his longtime valet Nicola D’Inverno. The dancers and singers play real historical figures and the audience knows that the stage illusions likely involve imagined incidents and occasional timeline disparities. It is worth noting that in the souvenir programs for these shows, the creators acknowledged their debts to research on Sargent. The ballet was inspired by Deborah Davis’s 2003 narrative nonfiction book Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X. The opera began its evolution after the librettist learned about Boston’s Apollo: Thomas McKeller and John Singer Sargent, the catalogue and shrewd pocket exhibition created at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 2020.

Meanwhile, curators tasked with developing blockbusters for big museums remain fearful about discussing the artist’s sexuality and how it impacted his art. The catalogue for the exhibition Fashioned by Sargent (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2023) conceded the topic by noting “the much debated and unresolved question of Sargent’s (homo)sexuality.” It also referred to “the homosexual and homosocial circles in which he often moved.” This year – the 100th anniversary of the artist’s death – New York’s Metropolitan Museum gave some limelight to a few early oil sketches of sexy men in its exhibition Sargent and Paris. Alas, the wall texts did little to help viewers fathom the sensual display. The main exception concerned a bust-length painting of Parisian art student Albert de Belleroche in 16th-century costume. The accompanying label said the subject’s “chiseled features, angular jaw, and hooded eyes represented a type of beauty [Sargent] found appealing.” Then came a disclaimer that strategically bowed to the Tate’s 1998 dictum: “Sargent’s images of Belleroche have fueled speculation that their relationship was romantic, though Sargent was extremely private about his personal life and left no overt evidence of any liaisons.” The institutional voice chose not to “see” Sargent’s painting of Belleroche as a form of “evidence.” The work is, nonetheless, a considered visual statement made in response to the artist’s feelings for the man.

Trevor Fairbrother recently wrote an essay about Sargent for Donald Platt’s book-length poem Tender Voyeur, published by Grid Books. His first contribution to The Arts Fuse was “Boston and Sargent, For Better, For Worse” (December 31, 2023). He dedicates this essay to Alfred J. Walker (1938-2025), the big-hearted Boston gallerist and arts patron who helped the MFA purchase Nude Study of Thomas E. McKeller in 1986.