December Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Jazz

Saxophonist Rick Keller teaches at UNLV, and on Heroes he and his bandmates are doing the musical equivalent of Las Vegas celebrity impressions.

Saxophonist Rick Keller teaches at UNLV, and on Heroes he and his bandmates are doing the musical equivalent of Las Vegas celebrity impressions.

Some tracks are more literal than others. “For Pat” captures that glossy Pat Metheny Group sound from the 1980s, but it doesn’t have the dramatic narrative arc of a PMG masterpiece. “Us Against the World” is a dead ringer for a grooving Tower of Power track, thanks in large part to the help of TOP member Carmen Grillo. Keller overdubs on that crucial funky baritone sax.

Best are the two tributes to Michael Brecker. Keller has Brecker’s style down absolutely cold. He could fool people on a blindfold test. All the details are right—the vibrato at the ends of phrases, the articulation, the little trills, and the dynamics. Keller has done his homework!

Other tributes are more hazy. The Weather Report tribute doesn’t do justice to Wayne Shorter’s sound, and there’s a short synth solo with a tip of the beanie to Zawinul, but this acoustic ballad is far from WR’s signature sound. Worst of all is the smooth jazz concoction with cheesy vocals that’s a tribute to the Headhunters in name only.

Oregon gets a six-song suite. Percussionist Tim Sellars acquits himself admirably in the difficult role played by the masters Collin Walcott and Trilok Gurtu. While the songs miss some of the delicacy and charm of Oregon’s originals, they salute the group’s world music feel in the unusual time signatures and interplay between the acoustic guitar and bass. As a suite, they throw off the already highly uneven concept of the album. They seem to belong on a different CD. But there are some moments, especially on the lovely final “Hymn,” when we hear Keller sounding like himself and singing his own song on tenor.

— Allen Michie

True freedom is not recklessness. But at times, free jazz inevitably challenges the listener to draw a dividing line. For those not comfortable with expansive sonic liberties, the results may sound like walks on the crazy side.

True freedom is not recklessness. But at times, free jazz inevitably challenges the listener to draw a dividing line. For those not comfortable with expansive sonic liberties, the results may sound like walks on the crazy side.

Roscoe Mitchell has long been promoting freedom, both through his music and his communitarian efforts. Starting with his participation in and leadership of the Art Ensemble of Chicago and the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, he has remained a steady innovator whose experiments in sound have never gone stale. Now past 80, Mitchell is still exploring demanding new territory.

IN 2 (RogueArt) finds the saxophonist (sopranino and bass sax with percussion) in duet with Boston-educated, Italian percussionist/electronicist Michele Rabbia. This co-written set of music sometimes suggests an intriguing series of intermezzi from an Art Ensemble concert — brief but compelling, and a little strange.

“A Night in the Forest,” at 10:57 minutes, is the longest cut on the disc. The noises made by Rabbia’s initial taps and resonant hollow tones reminded me of the raps the old pipes underneath my kitchen sink sometimes make. But then electronic tones arrive, and they add a more interesting and mysterious dimension. Bells and gongs begin to toll at length — before a clearing is eventually reached.

Though it precedes that track on the disc, “A Day in a Forest” would make for a refreshing breather after a long night of tapping. Mitchell breathes (literally) life into the cut through his mouthpiece. In “Interaction” the saxophonist employs both of his horns to generate a sense of thoughtful alarm.

The thick tones of Mitchell’s bass sax in “Low Answer” call to mind the lonely emanations of the late composer Ingram Marshall’s haunting soundscape “Fog Tropes,” while the title cut offers a brief burst of energy, proving that Mitchell can still supply his distinctive brand of frenzy.

Mitchell’s sopranino sax plays a predominant role on the following track, “First Impression.” As Rabbia churns on his drum set, the sax man truncates his story through a succession of squeaks and cries.

This duo’s meet-up offers intimations of synthesis. And that’s the beauty of it.

— Steve Feeney

Highly talented tenor saxophonist Kevin Sun’s latest album, out on his Endectomorph Music label, is Lofi At Lowlands. It is a trio setting with bandmates Walter Stinson on acoustic bass and Kayvon Gordon on drums, recorded at the Lowlands Bar in Brooklyn. The recording is much more experimental that his terrific previous release (the amply capacious Quartets); this outing utilizes overdubbing, sampling, and various strategies of sonic reordering. There are nine tracks, six of which are just over a minute — the listener must pay close attention to the detailing.

“banshees”, the first track, has the trio working in a determined avant-garde mode for almost five minutes, before it kicks into overdrive. In the next two songs Sun’s cohorts are given plenty of room to display their abundant talents. Stinson makes great use of the bow in his solo turn on “gorgonry” and Gordon busts out on the appropriately named “fissures”. The trio comes together on “the scars on a glaze”, which ends abruptly. ending. “praise the run” is the most intriguing cut on the recording. The trio gathers itself into a great force of sound, dipping into the innovations of the early ’60 jazz. For a brief seventy-five seconds, Sun’s tenor drives the tune into the stratosphere. The distortion of Stinson’s bass is among the surprises here, particularly during his foray up and down the fret board on “floral deceit”. “time-warped blues” is the final track, with Gordon and Stinson doing a bass and drums thang.

Alas, the listener does not get enough of the impressive tenor playing of the leader on this recording There is plenty of interesting interplay here, but I kept wanting to hear from that wonderful horn. Granted, Stinson and Gordon have prodigious gifts to share — the tracks where they play are solid. But Lofi At Lowlands is a Kevin Sun production that serves up just a little taste of the leader.

— Brooks Geiken

Folk

If folk music means maintaining connections to past traditions, Irish singer Lisa O’Neill upholds that definition. She sticks with acoustic instruments. On her new EP, The Wind Doesn’t Blow This Far Right (Rough Trade), she sets the words of poets James Stephens and Christina Georgina Rossetti to music. In addition, she covers Bob Dylan’s “All the Tired Horses,” which was used in Peaky Blinders’ final episode. O’Neill has a prominent enough place in Irish music that she sang Kirsty MacColl’s part in the Pogues’ “Fairytale of New York” at Shane MacGowan’s funeral.

Her own compositions focus on the lives of ordinary people in her rapidly gentrifying country. “Mother Jones” is a biography of the Irish-American union activist. O’Neill becomes more up to date with “Homeless in the Thousands (Dublin in the Digital Age).” She sings “they were homeless in the dozens when I was a kid,” critiquing increasing urban gentrification, noting that the turn towards a cashless economy means that people don’t even have spare coins to give away. She’s a talented storyteller, and this tune chronicles the city’s changes through the life of one poor woman.

O’Neill tends to start her songs with wintry, harsh drones and then develops them in layers. She has a knack for using these mounds of sound in her tunes to build up to dramatic conclusions. For example, the harmonium on “Autumn 1915,” the EP’s most abrasive song, cuts like a harsh fall wind as she intones Stephens’ words. These harsh musical strategies connect directly to politics. The EP’s title track warns listeners about the rise of fascism. O’Neill’s guitar on “Mother Jones” snaps and resonates like a snake about to bite. Only the aching melody of “The Bleak Midwinter” approaches prettiness. This is not folk music as nostalgia—her allusions to Ireland’s history stress the need for perpetual struggle against injustice.

— Steve Erickson

Books

In 2001, writer Brad Kessler and photographer Dona Ann McAdams collaborated on The Woodcutter’s Christmas. Inspired by her photos of discarded Christmas trees, Kessler penned a tender holiday tale of a farmer’s annual trek from Vermont to sell his family’s stock of trees to Manhattanites.

In 2001, writer Brad Kessler and photographer Dona Ann McAdams collaborated on The Woodcutter’s Christmas. Inspired by her photos of discarded Christmas trees, Kessler penned a tender holiday tale of a farmer’s annual trek from Vermont to sell his family’s stock of trees to Manhattanites.

The slender volume has long been out-of-print. However, Galpón Press has released an updated edition with expanded text by Kessler and additional pictures by McAdams. There is so much to love in this book. The poetic prose — illuminated by austere black and white portraits of abandoned trees — is a resonant parable for all ages.

The story centers on a family’s fascination with a man who, every December, unpacks his truck and sets up an open-air bazaar of Christmas trees below their windows in the East Village. One night the reclusive salesman asks for help; he needs someone to watch his wares while he picks up a part to repair his truck. A meal is shared, and he scribbles his address, “Var’s Farm, Dedham’s Notch VT” on a matchbook cover. After that Xmas, he never comes back to that location.

Several years later, while returning from a ski trip in the Green Mountains, the family notices the Dedham’s Notch exit on the highway and decides to make a detour to visit the enigmatic farmer. Sitting by the man’s wood stove, the family learns that he became angry that his beloved trees were so quickly left for curbside trash. Disgusted, he filled his truck with the detritus and returned the trees back to the land, vowing never to return.

The story culminates with an agrarian miracle — the characters sit on the farmer’s porch, listening to the wind and trees as snow falls. It is a Zen moment in a sweetly spiritual yuletide fable that deserves to become a holiday classic.

— John R. Killacky

Daniel Swift, an associate professor of English at Northeastern University London, has written a deeply researched, nuts-and-bolts study that will no doubt fascinate bardolaters and anyone else interested in the nitty-gritty details of the evolution of Elizabethan drama. Chunks of the text deal with Shakespeare’s quest to reach the status of a money-making dramatist, the trials and tribulations of moving from the ground floor up. In this case, the ground floor should be taken literally. The Dream Factory (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 302 pages, $30) is a compelling narrative that examines what it took — in terms of blood, sweat, bluster, intrigue, and chicanery — to build, from 1576 to 1598, the Theatre, the first major playhouse dedicated to the commercial presentation of drama. This is the yard where the Bard threw his first theatrical fastballs (Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream) and, in 1599, its timbers would be hustled off to help erect the Globe.

The narrative supplies a close-up of the period’s scattershot transition from feudalism to capitalism, focusing on the structure of the guild system for workers in the city of London. Swift suggests that it provided a model for organizing the incipient business of producing plays, stages, and writers. He also draws intriguing parallels between dramatists and workers, probing how they rose in their professions and made a living. The bullying Richard Burbage and his family financed their idea of a profitable playhouse through loans and agreements (some more or less underhanded) that launched a thousand lawsuits. The legal and real-estate documents that survive are what provided Swift with the means to reconstruct the building and operation of the Theatre in all its rough-and-tumble, transactional glory, including positing the colorful personalities involved.

Meanwhile, The Dream Factory chronicles how Shakespeare found ways to keep afloat, both as his family’s breadwinner and a fledgling artist. Lit-crit sections delve into how the Bard’s early plays reflect the pragmatic vicissitudes of his profession, which was part of the gig economy of the time. Swift also hypothesizes that — during a scantily documented period in his life — the Bard served a stint as a play doctor; the arrival of the plague demanded that scripts be skillfully cut and condensed, because companies had to go out on tour.

— Bill Marx

An odd, slim novel with an insinuating punch, Daniele Del Giudice’s A Fictional Inquiry (translated from the Italian by Anne Milan0 Appel, New Vessel Press, 132 pages. $17.95), is narrated by what must be one of the most self-consciously reluctant investigators in literary history. The nameless protagonist (a writer? an academic?) is searching for the reasons behind a baffling refusal. Why did a deceased author — Italian writer and publicist Roberto Bazlen (1902–1965) — never publish anything in his lifetime? At this point, 1983, the year the novel was published, the man had been dead for almost two decades. Those who are left who could provide an answer to the question are now eccentric senior citizens in Trieste and London. They are duly visited by our hero, but he doesn’t seem to be interested in what they have to tell him; he is dismissive of their photographs, faulty memories, and gossip. Eventually, he closes his eyes once they pull out their albums.

An odd, slim novel with an insinuating punch, Daniele Del Giudice’s A Fictional Inquiry (translated from the Italian by Anne Milan0 Appel, New Vessel Press, 132 pages. $17.95), is narrated by what must be one of the most self-consciously reluctant investigators in literary history. The nameless protagonist (a writer? an academic?) is searching for the reasons behind a baffling refusal. Why did a deceased author — Italian writer and publicist Roberto Bazlen (1902–1965) — never publish anything in his lifetime? At this point, 1983, the year the novel was published, the man had been dead for almost two decades. Those who are left who could provide an answer to the question are now eccentric senior citizens in Trieste and London. They are duly visited by our hero, but he doesn’t seem to be interested in what they have to tell him; he is dismissive of their photographs, faulty memories, and gossip. Eventually, he closes his eyes once they pull out their albums.

As our enigma stumbles along in his journey (a train breaks down, he misses a few interview appointments), he tells us his goal, which may or may not have anything to do with Bazlen. He hopes to arrive at the special spot where “knowing how to be and knowing how to write perhaps intersect.” What we have here is a detective sent from the Jorge Luis Borges agency — a metaphysical sleuth, of the amateur rank.

Del Giudice’s first novel could be seen as a black comic burlesque of E. M. Forster’s adage “only connect.” The protagonist’s fixation on maps and schedules (there’s a dense and absolutely unnecessary section on how airline pilots navigate their course) collides with happenstance, such as a weird episode where the narrator watches someone steal a camera at Wimbledon Stadium. Still, you keep reading, because Del Giudice (1949-2021) pokes the guy’s sometimes sleepy, sometimes antsy consciousness into enticing existential nooks and crannies: “Sometimes it seems to me that nothing is more formidable than a void, or vacuum; It cuts though any issue, completes it, justifies it. As a visualization for feelings, a void is as remarkable as a flood or a sunset or a river …”

— Bill Marx

Art and Design

My mother told a story about our family’s visit to a large museum. I was 5 at the time. I refused to enter a painting gallery because a picture on the wall made me sad. My father went up to the painting and read the label — the image was about death. This upsetting experience may resonate with the confusion that’s felt by many visually creative children. Today, there is a growing library of children’s books about understanding and creating art and design. Three of these should be considered as every day or holiday gifts.

My mother told a story about our family’s visit to a large museum. I was 5 at the time. I refused to enter a painting gallery because a picture on the wall made me sad. My father went up to the painting and read the label — the image was about death. This upsetting experience may resonate with the confusion that’s felt by many visually creative children. Today, there is a growing library of children’s books about understanding and creating art and design. Three of these should be considered as every day or holiday gifts.

Pencil by Hye-Eun Kim is a beautifully illustrated wordless picture book. We see the products of the forest. Trees become pencils, and pencils create art. A pencil allows a young artist a key tool to an infinite imaginative world. However, a knowledgeable adult may have to explain the process. “Pencil” celebrates visual literacy skills and the creative process.

My First Shapes with Frank Lloyd Wright is a board book for toddlers inspired by FLW’s geometric style. It teaches basic shapes through illustrations and patterns drawn from Wright’s iconic architectural style. Crafted to be visually engaging through it use of bold colors, eye-catching patterns, and geometric forms, the volume will no doubt spark a youngster’s curiosity.

Author-artist Diana Ejaita’s Making Art celebrates the many ways we make art, spanning across mediums, geography, and resources. Here art is considered to be something for everyone — it can be created anywhere and with any materials. The imagination is inclusive, expansive, and even healing. The book’s easily understood text contains a large cast of characters exploring their feelings and ideas about creating, offering children a vision of what art can be, and the ways in which it enriches our lives.

Picasso once said “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up.” These three books underscore and maintain a child’s sense of wonder and the freedom to create.

— Mark Favermann

Classical Music

Poor Paul Hindemith. One of the most important and controversial composers active a century ago, he’s all but disappeared now, eclipsed by his contemporaries and short on high-profile champions. Of course, his own austere, sometimes rigid style might have something to do with that posthumous reputation.

At any rate, the ideas behind much of Hindemith’s output were hardly difficult. Like Bartók, he was fascinated by folk music and deeply invested in music education. Both items on a short Brilliant Classics release from the Orchestra Ico Suoni del Sud and conductor Marco Moresco are infused with these principles: Der Schwanendreher is a viola concerto based on old German folk tunes while the 5 Pieces are exercises for a student-level string orchestra.

The former is, by a good measure, the more interesting of the two. Its archaic melodic materials are dressed up in spiky, slightly Modernistic garb, but they’re still discernable. And it’s always nice to have a good showpiece for viola.

Soloist Luca Ranieri has all the notes in hand plus a good sense of where the line is headed. If his tone is occasionally steely, his playing is broadly lyrical and characterful. The second-movement duet between viola and harp is a highlight.

Alas, the accompaniments from Moresco and his forces are texturally cluttered and indistinct, as well as tonally monochrome. Rarely is there a sense of collaboration between the parties. Instead, a feeling of muddling through prevails and the reading sinks as a result. Better to stick with Tamestit and Paavo Järvi in this score.

The 5 Pieces don’t come off much better. Instead, the performance is raw and literal. Some vigorous violin solos in the finale aside, this is a recording that succeeds more at emphasizing caricatures of Hindemith rather than drawing out the humanity behind the notes he wrote.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

The Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich’s Mahler cycle with music director Paavo Järvi got off to an uneven start earlier this year with the Fifth Symphony. But the ship has been decisively righted in this second installment, which features a towering performance of the Symphony No. 1.

The Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich’s Mahler cycle with music director Paavo Järvi got off to an uneven start earlier this year with the Fifth Symphony. But the ship has been decisively righted in this second installment, which features a towering performance of the Symphony No. 1.

Mahler once quipped to a visitor admiring the view of mountains from his composing hut that he’d already composed the scene into his music. And you get a sense of that in this reading which, fittingly for a Swiss orchestra, evinces an enormous amount of natural space: the first movement’s quiet introduction unspools like a slow-pan of a stunning Alpine vista, the ländler boasts earthy zip, and the score’s various echoes of nature—birdsong, forests, storms—emerge viscerally.

Indeed, rarely does that second movement sound so convincingly rustic or the finale’s coda so brilliantly joyful. The last also benefits from a combination of good engineering and excellent balances: the exuberant string arpeggios that drive the section’s energy are audible amid the brass yawps.

But the reading’s most impressive aspect comes courtesy of the ensemble’s take on the bizarre third movement, with its mashup of Frère Jacques, klezmer bands, and art song references. Here, for pacing, color, and texture, Järvi and his forces demonstrate an outstanding grasp of the music’s narrative flow. As a result, there’s something uniquely, touchingly human about their account of some of Mahler’s most outlandish music. Those sentiments apply to the larger offering and bode well, one hopes, for the remainder of this series.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

On the surface, this is a strange pairing: what do Elgar’s sprawling Violin Concerto and Thomas Adès’ 2005 effort share in common? One is steeped in the language of Edwardian Romanticism, the other is a picture of 21st-century concision and acerbity. Yet in the right hands—namely those of Christian Tetzlaff, the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, and conductor John Storgårds—the fusion of opposites yields dividends.

On the surface, this is a strange pairing: what do Elgar’s sprawling Violin Concerto and Thomas Adès’ 2005 effort share in common? One is steeped in the language of Edwardian Romanticism, the other is a picture of 21st-century concision and acerbity. Yet in the right hands—namely those of Christian Tetzlaff, the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, and conductor John Storgårds—the fusion of opposites yields dividends.

A big part of what helps things work so well is basic: lively tempos in the Elgar. This is music that can easily take its time to say its piece—Elgar’s own recording from 1932 stretches to fifty minutes. Tetzlaff and Friends, however, come in at a fleet forty-three, which means that the big outer movements are fired with a special sense of urgency and passion and the Andante moves with beautiful purpose.

What’s more, the orchestral playing is outstandingly alert, both in terms of the score’s tricky, fluctuating phrasings and texturally. As a result, the whole performance sparkles like a newly-shined gem and yields all manner of expressive rewards.

So, too, does the Adès, which, despite its extraordinarily contemporary sonic profile, is clearly rooted in Romantic archetypes. Tetzlaff navigates the edgy, restless solo writing with astonishing fluency: at times this sounds like the sort of music Paganini might have written had he landed in London twenty years ago. Or Bach—the rhetoric of the central “Paths” calls to mind his great D-minor Chaconne.

As in the Elgar, the performers here are totally locked-in, both with one another and Adès gripping score, tracing the music’s dizzying, unsettling, and strangely comforting arcs with complete assurance and security.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

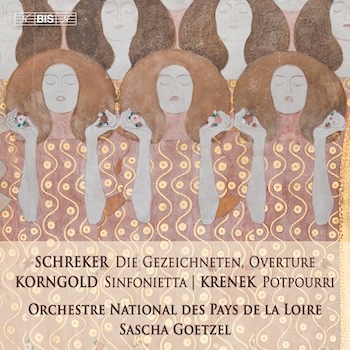

Franz Schreker, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Ernst Krenek make sense together. All stars of the early-20th-century German music, each member of the triptych staked out fairly distinctive ground, as a new disc from the Orchestre National Pays de la Loire and conductor Sascha Goetzel remind.

Korngold, a consummate man of the theater, became one of the iconic composers of 1930s Hollywood. His 1913 Sinfonietta suggests some of where he would end up: the off-balance rhythmic patterns of its Scherzo anticipate his score to The Adventures of Robin Hood and the finale is downright swashbuckling. At the same time, a tendency to drag things out a bit longer than necessary (a skill perhaps learned from Richard Strauss) crops up here and there, notably in the big first movement.

Nevertheless, Goetzel and his forces deliver a reading full of sweep and grandeur, as well as close attention to the little things. Textures are becomingly clear and subtleties in the scoring—like the flutter-tongued flutes near the end of the opening movement—speak delicately.

Krenek, too, was thoroughly cosmopolitan, though his music embraced all sorts of trendy devices, from jazz to Serialism. His Potpourri is decidedly cheeky and not a little discursive or episodic. Still, it’s a good bit of fun, especially in this reading, which is spirited, characterful, and stylistically assured.

Schreker charted a middle course between Wagner and Schoenberg, ending up formulating a distinctive voice that was banned by the Third Reich and has only recently started to be reappraised. The Overture to his 1915 opera Die Gezeichneten gives some sense of his mature vocabulary: rich, colorful, neither harmonically nor melodically predictable. Though the orchestral strings sound somewhat underpowered here, Goetzel & Co. find the magic in the music’s coloristic details, especially the writing for harps and celesta.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Dance

A scene from Third Coast Percussion’s Metamorphosis, performed at Arrow Street Arts. Photo: Robert Torres

Sometimes the best kind of design is contrast.

Chicago based Third Coast Percussion’s Metamorphosis, which the Celebrity Series brought to the lovely and still relatively new refurbished space of Arrow Street Arts in Cambridge Nov 22-23, juxtaposes marimba-forward classical and percussion with urban street dance, and uncovers the steady, anticipatory beat that ties them together. With massed marimbas and keyboards making a ledge like a horizon across the middle of the stage space, a small seemingly-carved out dance floor welcomed dancers Trent Jeray and Cameron Murphy in motion created by Lil Buck and Jon Boogz of Movement Art Is.

A collaboration created remotely while the world was in covid lockdown, Metamorphosis is a kind of precision juggling act, as the musicians wield their mallets, drumsticks and hands over a range of things meant to be struck (classical drum sets, cowbells, keyboards), things to blow into (melodica, bird whistle) and things that seem playfully invented to make cartoony squawks or just to see what hitting them can sound like. In works by Philip Glass, Jlin, and the saturated tonal colors of Tyondai Braxton (accentuated by Joe Burke’s Crayola bright lighting design) the musicians convey not merely pitch and complex rhythm – of course – but disclose the nature of the wood and metal materials with which these instruments are made.

Jeray’s confident toe-balancing, bent knee Memphis Jookin, flows along the musical line. Later the hypermobile Murphy will move like a 21st century Marcel Marceau, pulling himself up from the floor by invisible marionette strings. They’re virtuosos, but it’s odd that for dancers clearly able to do just about anything, this most abstract vernacular dance hits so hard on pantomime storytelling, complete with each man’s hand at his chest being pulsed outward by his beating, and possibly breaking, heart. But maybe everything that goes around comes around.

— Debra Cash

Tagged: "Der Schwanendreher", "IN 2", "Making Art", "My First Shapes with Frank Lloyd Wright", "Pencil", "The Wind Doesn’t Blow This Far Right", "The Woodcutter’s Christmas", 'Lofi at the Lowlands", BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, Brad Kessler, Christian Tetzlaff, Diana Ejaita, Dona Ann McAdams, Hye-eun Kim, John Storgårds, Kevin Sun, Lisa O’Neill, Marco Moresco, Michele Rabbia, Orchestra Ico Suoni del Sud, Orchestre National Pays de la Loire, Paavo Järvi, Roscoe Mitchell, Sascha Goetzel