Theater Interview: “Investigating the New” — Actor/Director Vincent Murphy Reflects on Life and Theater

By Bill Marx

What has made for a successful life in the theater? For Vincent Murphy, living by the values he imbibed as a member of Boston Children’s Theatre in the ’60s: “cooperation, creativity, listening, and play.”

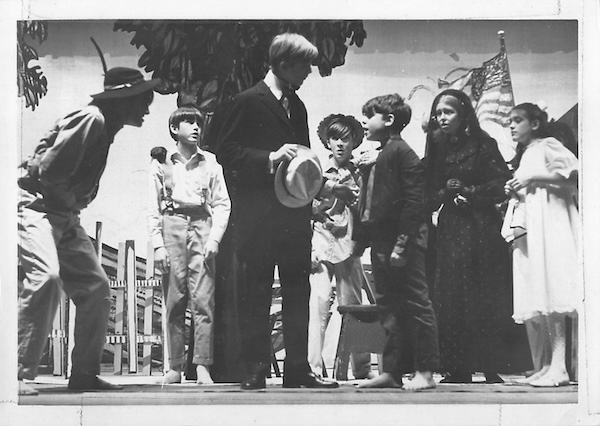

Vincent Murphy as Injun Joe (in profile) in the 1967 Boston Children’s Theater production of Tom Sawyer. Future director Julie Taymor is in black.

With age comes nostalgia, the temptation to kvell over the good old days. It must be resisted, of course, because the past was never as dandy as you remember it. But there was a time, back in the early to mid-‘80s, when it looked as if Boston-area theater was going to break free — or at least push away from — the dominant influence of New York. Theater artists and writers in and around our city were routinely producing original scripts in stagings that were not only of enormously high quality, but were also garnering national, in some cases international, recognition. That dream collapsed in the late ‘80s when one of the finest of these troupes, Theater Works, disbanded and its artistic director, Vincent Murphy, went down to Atlanta, where as the artistic director of Theatre Emory he developed a biennial Brave New Works series featuring the scripts of locally, nationally, and internationally prominent writers. He also founded the Playwriting Center of Theater Emory, where over one hundred new plays and adaptations were premiered.

What followed this group’s exodus (and others, though the Beau Jest Moving Theatre is still high-stepping) was New York’s slow absorption of too many of our city’s artists and the Big Apple’s colonization of most of what is produced here. For marketers, the words Broadway or off-Broadway– with Pavlovian charisma — ensured consumer satisfaction. At this point in time, we have one of the country’s major regional theaters, the American Repertory Theater, no longer hosting a regional company of actors as it goes about the business of feeding the Great White Way. The dream of a local theater scene that generated its own innovative theater artists – and kept them in town – is a memory. But those memories remain prophetic of what Boston theater can be. Theater Works’ productions of Me and My Shadow (an staging of a short story by the late John Barth) and They all Want to Play Hamlet (starring the great Tim McDonough) and others, including powerful versions of Edward Bond’s The Bundle and Samuel Beckett’s Enough, remain, in my mind, among the high points of local theater production — new plays, original visions, bravura acting, innovative stagings.

So I turned to director/actor Vincent Murphy’s memoir Caught: A Kid with a Cup with enthusiasm. Frankly, I would have liked more about Theater Works and how it accomplished as much as it did. But Murphy, to his credit, is not into nostalgia. Or gossip or backstage anecdotes, though there is an amusing story of when, as a performer, he was directed by John Cage. The volume is a hop-skip-and-jump celebration of life flashing by, in which the director talks about surviving his dysfunctional family in Boston’s Columbia Point Housing Project, his love for the theater (inspired by his stint as an adolescent performer in Boston Children’s Theatre), his international travels, working with regional theaters and renowned artists throughout the world (he includes a warm recollection of Athol Fugard) and, most gloriously, his commitment to creating provocative theater that “investigates the new,” including through challenging adaptations. (Murphy’s approach to the latter is detailed in his 2013 book Page to Stage.)

So I turned to director/actor Vincent Murphy’s memoir Caught: A Kid with a Cup with enthusiasm. Frankly, I would have liked more about Theater Works and how it accomplished as much as it did. But Murphy, to his credit, is not into nostalgia. Or gossip or backstage anecdotes, though there is an amusing story of when, as a performer, he was directed by John Cage. The volume is a hop-skip-and-jump celebration of life flashing by, in which the director talks about surviving his dysfunctional family in Boston’s Columbia Point Housing Project, his love for the theater (inspired by his stint as an adolescent performer in Boston Children’s Theatre), his international travels, working with regional theaters and renowned artists throughout the world (he includes a warm recollection of Athol Fugard) and, most gloriously, his commitment to creating provocative theater that “investigates the new,” including through challenging adaptations. (Murphy’s approach to the latter is detailed in his 2013 book Page to Stage.)

Murphy notes what has worked against him in his theater career: “too-high standards, a reputation as a gadfly, a penchant for not walking away from a fight, the soul sickness brought on by sham, a belief in constructive criticism, and an annoyance at too many trophies given for any level of advancement or achievement.” What has worked for him through the decades? Living by the values he imbibed as a member of Boston Children’s Theatre in the ’60s: “cooperation, creativity, listening, and play.”

Via email, I sent Murphy a few questions about Caught.

Arts Fuse: Why write this memoir now? And what would you like a reader to take away from it?

Vincent Murphy: I didn’t set out to write a memoir. I had written several travel stories some years earlier, but during Covid I found myself with the opportunity to join a writer’s group online and a significant number of these stories grew out of that opportunity. I’m hoping the readers can relate to a story about becoming, about finding a door to open toward being the someone you want to be, not be what is dictated to you. It’s also about a survival mode for a life in theater.

Vincent Murphy

AF: Talk about the importance of children’s theater to you — and how do you think it is doing now, in Boston and elsewhere?

Murphy: I was forced to join Boston Children’s Theatre by my mother’s welfare worker after I was caught stealing. Boston Children’s Theatre was a great gift. There was an openness to working seriously with young people both with intense demands and respect. (And I got to be the Prince to Julie Taymor’s Cinderella and then date her and experience another experimental theater in Boston with her. Boston Children’s Theatre unfortunately collapsed due to some mismanagement and abuse.

AF: Why did Theater Works leave Boston in the late ’80s? And why didn’t another company run with your vision here?

Murphy: Theater Works had a remarkable and substantive run for about seven years which I think is the molting age when you begin to shed the skin of whatever you’ve created and you need to find a reason to go on. We never made a living from doing Theater Works even though Robert Brustein invited us to do They All Want to Play Hamlet on the main stage at American Repertory Theater and Joe Papp got interested in producing it. But there are new possibilities for innovative theater. My daughter Ariel Fristoe has pioneered a new idea of how theaters can thrive and survive and was flown from Atlanta, where she created the Out of Hand Theater company, to the Harvard Business School, which spent two days surveying her innovative idea of how theaters can both be connected to communities and find the necessary funding for people to have a livable career.

AF: Throughout your career you have been committed to producing new work. You have not gone into film. Talk about why you are so dedicated to staging original plays.

Murphy: There is nothing so fulfilling and inspiring as being in the act of creation. Constructing plays in collaboration with playwrights like Jon Lipsky or adapting Beckett or Ondaatje and creating a vision with remarkable actors like Tim McDonough is where the meeting of your sensibility, your history, your concerns and your inspiration meet to investigate the new.

AF: You note your extensive travels and stage productions throughout Caught. (I ached to see some of the shows you reference.) But there is little physical description in the book. Why is that?

Murphy: What makes theater so remarkable to me is that it lives and dies at the same moment. When you see a film, you know you can always go back to it again and it will always be the same. Only you have changed. Theater must live in the moment, must live with its eyes wide open and its heart beating fast to attend to an audience that is there to be thrilled and challenged. You must live in the moment to do it. I saw an astonishing production of Tristan & Yseult by Kneehigh Company in New York and then, when it came to Boston, I gathered a group of eight friends and bought them tickets to see it. It was everything you wanted theater to be: alive, questioning, funny, big hearted, intelligent. I heard that the company had done even better productions, so I went to the Lincoln Center Theater library archives to view a couple. There is simply no way of having a play recorded that would give you the experience of what it’s like to be in the audience and in the moment that the actors are engaging you.

AF: What has changed for the better — and for the worse — in American theater over the past four decades?

AF: What has changed for the better — and for the worse — in American theater over the past four decades?

Murphy: Theater now speaks with multiple voices. Most of the major artistic directors that I admire are women and that would not have been true 20 years ago because they didn’t get those jobs. Theater will always be scrappy, will always be that friend and enemy in the room who can tell you exactly what’s going on.

AF: What is next for you?

Murphy: My career at Theater Works was often about doing adaptations of material that I admired and that haunted me. I continue to do that at several theaters across the United States, in Canada, Europe, and in South America. While I was Artistic Producing Director of the resident equity Theater Emory in Atlanta I started teaching master classes in adaptation. While looking for a good source material I found some helpful articles, but there was no textbook to guide us through this significant method of creating. So, a couple of decades ago, I wrote the first book on theatrical adaptation while I was on sabbatical living in Florence Italy and could employ all those ancient libraries to write and think in. I continue to teach my “Page to Stage” workshops.

I’m living between New York City and Berlin. I watch out for theater artists that can be supported as an original trustee in 1999 of the Tanne Foundation which was set up by an actor from my Theater Works company and gives unrestricted money to artists in all disciplines to encourage their risks and vision. I also use whatever connections I must to help playwrights make connections to theaters. I have a visionary project called Sister City Playwrights that is outlined in Caught that unites play labs across the USA and Canada and England. Recently, there is a playwright whose work I believed in that needed to get out there, so I organized, directed, and produced staged greetings of five of his works at Seven Stages in Atlanta this past November. I’ll be meeting with Nora Hussey while in Boston about directing a reading for him in Boston.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

I experienced and participated in the work that Vincent and Tim did, as I imagine a lot of people reading this did. Their work, along with Jon Lipsky’s writing and Steve Cummings’ music, made for halcyon days in Boston theater. Thanks, Mr Murphy.

Here comes a comment from the other side of the Atlantic.

I really love your sentence:” What makes theater so remarkable to me is that it lives and dies at the same moment.“

You write, “… about finding a door to open toward being the someone you want to be, not be what is dictated to you.” Is that possible with theater? As an actor, don’t you slip into a different role? Or is this role perhaps more like yourself than outside in everyday life? And who do I identify with as a spectator?

Maybe I’ll get an answer?

Oh, sorry, one more quick question about modern times:

What is theater in the age of AI? Do you perhaps need to write a new book titled “pAIge to stAIge”?

I was an actor in the Boston Children’s Theatre shortly after Vincent Murphy’s time. He is absolutely right: when Adele Thane and George Roland were in charge, the creativity and professionalism that reigned at BCT were profoundly inspiring. Unfortunately, after they retired, an entirely new management took over that brought all manner of changes, betraying the foundation of BCT, which was, “Children performing for children”. Adults were cast, and the theatre’s unique mission was tossed aside. By the 21st century, it bore no relation to the original theatre; it had even left Boston. In 2017, the reorganized theatre put on a controversial production featuring nudity, which demonstrated the new regime’s negligence and irresponsibility regarding child performers. Worse was to come. Two years later, the director of that production was accused of inappropriate behavior with child actors, and this, combined with financial difficulties, brought down the theatre entirely. The corruption of BCT’s original vision and how its downfall has contaminated its legacy is heartbreaking. Generations of performers, like Vincent Murphy and myself, owe such a debt to Adele Thane and George Roland, not to mention the tens of thousands of children in the audiences of their productions. BCT presented a theatrical vision grounded in the oldest traditions of the theatre, and more importantly, one that respected and treasured the shimmering delicacy of childhood fantasy. Let the memory of that vision prevail.

Great, Tom! And how true.