Theater Review: Propeller Theatre Company Takes Off

Buckets of blood and handfuls of guts always look slightly ridiculous splashed and dangled around the stage, though I must admit that this is the first production of Richard III I have seen with a working chainsaw.

The Comedy of Errors and Richard III by William Shakespeare. The Propeller Theatre Company productions presented in repertory by the Boston University School of Theatre in association with the Huntington Theatre Company, at the Boston University Theatre, Boston, MA, through June 19.

By Bill Marx

In his Director’s Note in the Huntington Theatre Company program, Propeller Theatre Company artistic director Edward Hall rejects critical characterizations that the British troupe’s physical/musical approach to Shakespeare’s texts is about making the plays more accessible to audiences, arguing that this implies “they need dumbing down in order to be understood.” Based on seeing both The Comedy of Errors and Richard III on the same day, I would argue that Hall’s approach isn’t about simplifying so much as souping the proceedings up via a knockabout playfulness that whizzes by complexity, an approach that fits wild farces such as The Comedy of Errors much more comfortably than the bloody dramatics of Richard III.

At the end of his Note, Hall observes that one play is a comedy and the other a tragedy and asks “Which is which …?” Besides raising the issue of whether Richard III is a history, a tragedy, or both, the question is pretty easily answered: The Comedy of Errors comes off as a generally rollicking laughfest, good ,frenzied fun at its best, but the campy take on Richard III (set in the Victorian era) descends into standard horror/comedy, partly because of its Grand Guignol-lite/slasher-film trappings.

Buckets of blood and handfuls of guts always look slightly ridiculous splashed and dangled around on stage, though I must admit that this is the first production of Richard III I have seen with a working chainsaw. Still, we only hear Lord Hastings’ head noisily removed, splattered blood on plastic curtains the stereotypical (and disappointing) visual. Having Richard walk over body bags to the crown and not only refer to the death of his victims (such as Lady Anne) but doing it himself (in his fantasy?) is pictorial overkill in a play already dedicated to overkill.

Despite an amusing opening featuring festive music performed by the all-male Propeller company wearing sombreros and a comical policeman strolling through the audience warning us about cell phones, The Comedy of Errors starts out dead serious, though not in a conventional way. The Syracusian merchant Aegon ends up in Ephesus (a Spanish vacation spot for Brits?), sworn enemy of the people of Syracuse, and tells his sad tale of a missing wife, son (one of his identical twin sons, both named Antipholus), and slave (also with an identical twin, both lads named Dromio) to the Duke of Ephesus. The latter holds up a gun to the old man’s head but relents, giving him a day to raise enough money to save his life.

To make Aegon’s long monologue affecting takes thoughtful care. Here it gets a boilerplate treatment—the firearm represents Hall’s visceral approach. He invents physical business to match or augment what the verse says or suggests, often going to the point of buffoonery. This works well when the comic actions and outlandish images grow out of the text (given that Hall’s Richard III is shot to death, The Duke of Ephesus’s gun is an interesting touch), but at times the goosed-up stylization and anachronisms become more about desperation than imagination, especially when the ideas float in out of thin air. Why is Luciana, the sister of Adriana, a master of Jujitsu?

At worse, the jokes devolve into rote sign language: when money is mentioned characters rib their fingers together. The use of music is effective (turning the conjurer Pinch into a born-again Christian huckster/songster aptly rattles the walls), though sometimes the tunes feel like Hall’s extra-Shakespearean default. The company’s verse delivery is clear and forceful, though not particularly ambitious. Most of the cast’s energy goes into putting physical spins on the play’s action, not looking for a way to spin Shakespeare’s verse in revealing ways. Hall serves Shakespeare’s language, but he doesn’t entirely trust it, not when a pair of nunchucks are within easy reach.

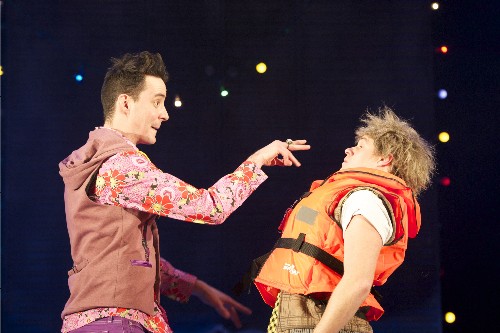

Sam Swainsbury (Antipholus of Ephesus) and Richard Frame (Dromio of Syracuse) work out a misuderstanding in THE COMEDY OF ERRORS. Photo: Manuel Harlan.

But The Comedy of Errors is inspired slapstick, and once the production picks up steam, there are giggles and pratfalls aplenty. My favorite performers include Richard Frame as the Dromeo of Syracuse—he makes the sexist spiel about his overweight Ephesusian wife outrageous enough to be both hilarious and absurd; the passive/aggressive wooing of David Newman’s Luciana and Dugald Bruce-Lockhart’s Antipholus of Syracuse is the liveliest treatment of this scene I have ever seen— it is a rare moment when the laughs are generated by clashing emotions rather slam-bang extracurricular business. The costumes are technicolor flavorful, the spirits of the performers high, their timing rat-a-tat-tat sharp, and the actors playing the female roles sashay with gritty aplomb—an evening of antic entertainment.

As I suggested above, the Propeller production of Richard III is more problematic, partly because the play blends the exhilaration of narcissism with a fascinating analysis of what drives the resulting carnage as well as a sympathetic view of its victims. The tone can’t veer too far into black comedy since Shakespeare covers his Marlowian tracks by serving up many (far too many for my taste) figures sincerely denouncing the title monster. What’s more, the play is as much about helplessness as it is about devilish derring-do. Richard is a man with a grudge—”Deform’d, unfinish’d, sent before my time / Into this breathing world”—and he uses this sense of primal injury to invent his own morality, or at the least to disregard what others accept as ethics. He overcomes rather than accepts his perception of impotence, idealizing himself by embracing the power that comes from being feared and hated. (There is a little Richard in all of us.) He faces his endemic helplessness, in the form of abject isolation, only at the end of the play.

Thus the villain is simultaneously powerful and weak—a duality brilliantly caught in Anthony Sher’s 1985 interpretation of the role for the Royal Shakespeare Company, in which Richard scurried across the stage on long, metal spider legs, horrifying artificial appendages protecting a shriveled body. The play’s examination of how we react to helplessness is also caught in the cursing and keening of Richard’s foes—these figures are continually praying that their sharp calls for revenge will be more than a waste of breath, with one scene revolving around how best to make a denunciation of Richard bear fruit. When does wishing for justice make it so for the marginalized?

In the Propeller production, Richard Clothier is a bit too self-consciously chuckle-ish as Richard III—a Henny Youngman of doom, you can almost hear the drum rim shots following his lethal one-liners. Sardonic, charming, childlike, impatient, a sociopath, Clothier’s Richard III is many things but not a man bearing an elemental chip on his shoulder—the emphasis of Hall’s staging is on the grotesqueness of Richard’s crimes against humanity rather than on the deformation of his soul.

Tony Bell (Queen Margaret), Kelsey Brookfield (Duchess of York), and Dominic Tighe (Queen Elizabeth) watch the puppet heads float in RICHARD III. Photo: Manuel Harlan.

Hall’s staging moves along with dispatch, the hodgepodge of ideas ranging from the inspired (King Edward’s young sons are life-sized puppets) to the intriguing (Richard III and the Earl of Richmond dream back-to-back as chatty ghosts parade by), from the predictable (everybody is costumed in Goth-inspired black but England’s savior, the Earl of Richmond) to the obvious (Richard III grinding Lady Anne into the corpse of her dead father-in-law, King Henry VI). The white masks on the cast members lose their Halloween eeriness early on, and the blood sprays aren’t nearly as frightening as the deadpan announcements of murder.

The Propeller cast members are nothing if not versatile, but the most effective moments and performers are limited to evoking (or sending-up?) Richard III‘s grisly comedy, including a cockeyed ending that pays satiric homage to the Hollywood cliche that super creeps take extra ammo to finish off. The Comedy of Errors proves that Propeller can whip up Shakespearean comedy: too bad the troupe only stages Shakespeare, because its preference for physical attack would be perfect for Ben Jonson’s The Silent Woman, Alchemist, and Bartholomew Fair. But based on its more often spoofy than spooky Richard III, I reserve judgment on Hall’s success with Shakespearean tragedy and history, whichever is which . . .

Tagged: Edward Hall, Huntington-Theatre-Company, Propeller Theatre Company, Richard III, The Comedy of Errors