Theater Feature: Edward Gorey Takes the Stage

Author Carol Verburg covers a sinfully neglected part of Edward Gorey’s career—the books on his art deal cursorily, if at all, with his forays into theater as a director, designer, actor, and writer.

Edward Gorey Plays Cape Cod: Puppets, People, Places & Plots by Carol Verburg. Boom Books, 30 pages, $9.99.

By Bill Marx

It isn’t often that you wish a piece of writing about the theater was longer than it is, but Carol Verburg’s pamphlet about her days working with artist Edward Gorey, when he decided to write and produce “entertainments” (plays, revues, puppet shows) on Cape Cod, leaves you regretting its slimness. Essentially, Verburg’s low-cal look back at producing and stage-managing a number of Gorey’s plays serves as a chatty introduction to his texts, which will be published sometime in the near future.

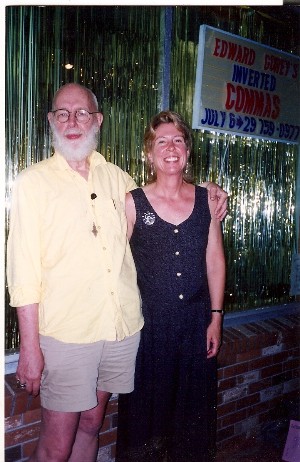

For now, Verburg offers invaluable facts and intriguing tidbits about a sinfully neglected part of Gorey’s career—the books on his art deal cursorily, if at all, with his forays into theater as a director, designer, actor, and writer. Yet as Verburg documents in Edward Gorey Plays Cape Cod, from the late 1980s until his death in 2000 Gorey created over two dozen theatrical pieces based on his stories and illustrations. Why he turned to the stage is left nebulous: the death of George Balanchine ended his love of the New York Ballet; the success of the Broadway production of Dracula, for which Gorey designed Tony award-winning sets and costumes, made buying a home in Yarmouth Port possible; the tantalizing fortunes of the stage adaptations Gorey Stories and Amphigorey: The Musical; meeting impressive stage talent on the Cape.

Whatever the reasons, Verburg shows that Gorey took theater seriously, providing plenty of nuts and bolts detail about the productions, which were generally mounted in the summer. He was a one-man creative band: Gorey attended every performance, “hand-sewed all 200-odd costumes” for his company of puppets, Le Theatrical Stoique, supplied all the art for the productions (including mugs, T-shirts, posters), and typed each script out on his manual typewriter.

According to Verburg, who stage-manged many of the shows, Gorey was generally a hands-off director; “although he usually had an idea how he wanted a piece to look and move onstage, he left most of the details—including who should play which parts—up to the actors.” We are given some insight into how he fashioned his askew dramas; he stuck loyally to a small cadre of actors (“Naivete charmed him; slickness irked him”), put in private jokes, and seldom changed the script once rehearsals started.

But Verburg but doesn’t really go into much hard analysis—what was it that Gorey learned about himself and his art by going into the theater? Instead, the text proffers personal reflections on working with Gorey, “an inimitable, irreplaceable collaborator and friend.” There are amusing stories (“One night during Chinese Gossip, two tipsy men wandered in and tried to order takeaway”) and moving anecdotes, such as that on Gorey’s death bed he was read to from his favorite book The Tale of Genji.

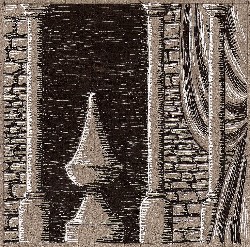

As for the shows, they are impish surrealistic delights, flyblown fantasies that slap the face of American earnestness. Their titles suggest mischievous silliness: Moderate Seaweed, Crazed Teacups, and Blithering Christmas. I was privileged to review 1996’s Heads Will Roll & Wallpaper for The Boston Globe and had the rare opportunity to see Gorey himself on stage, costumed in shorts, playing what looked like a “superannuated Boy Scout” who kept popping up to deliver mysterious messages to a doomed crew of stuffed shirts. It turns out that the cast was doing its best to make him crack up, but I can testify that Gorey’s buttoned-down demeanor remained inviolate. As I wrote then,

“Gorey takes to the footlights on little bat’s wings. Gorey’s stage work has the same air of impromptu surreality as his books; his scripts are stripped-down, deadpan send-ups of Victorian conventions, from damsel-in-distress melodramas and moralistic children’s tales to pornography.”

Verburg’s text will no doubt help to kick start interest into Gorey’s theatrical efforts, perhaps sparking some revivals. She will be speaking about Gorey and the stage at the Edward Gorey House in Yarmouth Port at 12 p.m. on Thursday, June 9, 2011. It is part of an ongoing exhibit on Edward Gorey and the Performing Arts, which includes work he did at Harvard, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York City Ballet, his “entertainments” on Cape Cod, and many more.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Some of Gorey’s drawings for theater, and at least one of his hand-sewn critters, are on view right now at the Boston Athenaeum’s terrific exhibition, “Elegant Enigmas: The Art of Edward Gorey.” (See The Arts Fuse review.) It’s a great collection of work from throughout Gorey’s career. It’s only up through June 4, so hurry up and catch it!

emailed review to Cape Cod friend who worked with Gorey in theater for 13 years.