July Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Popular Music

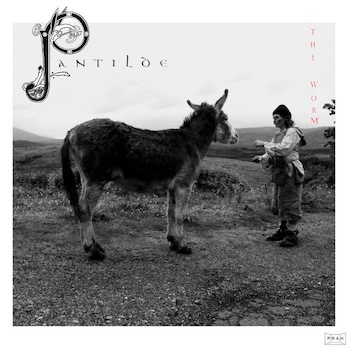

The Worm’s Pantilde (PRAH Records) is one of the most eccentric albums you’re likely to hear in 2025, a high-concept alternate history set in Cornwall, England. Created by performance artist Amy Lawrence, this ambitious project summons up an alternate history of Celtic life. Music is just one part of the band’s expressive vision. Even without visuals, the songs imply their presence, but the pastoral setting is a psychedelic countryside of the imagination, based on an actual place.

Very few musicians base their sound on the recorder, which is often given to young music students. Although it’s far from the album’s sole instrument, its high-pitched, flute-like tone dominates Pantilde. The hummed vocals, harp, and shaker of “Grass Grows Pt. 1” set a childlike mood. The layered “Heva’s Village” is far more dissonant. “The Clown Is Free” shows the band’s gift for melody — a brief series of notes is repeated, then replaced by a harsher, more hectic tone.

The Worm has released a song-by-song explanation of Pantilde, but the music here remains difficult to grasp. They sing from the perspectives of a donkey (the album’s titular character) and a creature “born 13 million years ago/my mother was the moon, my father was the star.” “Portal” launches them into a time travel portal.

As minimal as its instrumentation is, Pantilde still manages to be varied. Its songs are built from a few simple elements, but they’re constructed with real sophistication. The breezy melody that begins “The Clown Is Free” is shattered into a tougher, more frenzied direction. While Pantilde sounds entirely acoustic, it incorporates buzzes and drones. (The Worm has even commissioned dance mixes from the album.) The band acts out its nerdy fantasy with delight, all the while engaging with Celtic mythology. The only constant, as The Worm sings, is the fact that “I’m going on a journey.”

— Steve Erickson

Tropical Fuck Storm have a way with song titles. Among the examples on Fairyland Codex (Fire Records): “Dunning Kruger’s Loser Cruiser” and “Joe Meek Will Inherit the Earth.” The Australian band faces down terror — “the golden age of assholes, the triumph of disgrace,” as the band describes it — with a wicked sense of humor. Their lyrics throw out surreal references that call for further research: “Irakundji Syndrome” describes a sailor’s hallucinatory encounter with a monstrous jellyfish.

Tropical Fuck Storm have a way with song titles. Among the examples on Fairyland Codex (Fire Records): “Dunning Kruger’s Loser Cruiser” and “Joe Meek Will Inherit the Earth.” The Australian band faces down terror — “the golden age of assholes, the triumph of disgrace,” as the band describes it — with a wicked sense of humor. Their lyrics throw out surreal references that call for further research: “Irakundji Syndrome” describes a sailor’s hallucinatory encounter with a monstrous jellyfish.

While guitarist Gareth Lilliard handles most of the vocals, TFS doesn’t really have a lead singer. Bassist Fiona Kitschin and guitarist/keyboardist Erica Dunn offer responses to his words and harmonize with him and each other, but they also take the mic on several songs. Rather than typical choruses, their songs throw out phrases like “private life” as repeated mantras.

TFS’ songs burrow deep into the absurdity of modern life. “Dunning Kruger’s Loser Cruiser” raises metaphysical questions about how technology’s is destroying privacy; the song yearns for a life beyond surveillance knowing full well that it has become an impossibility. Although they can stir up winds of malevolence, TFS also notes that kindness serves as an important antidote. When Lilliard sings about love, as he does on “Stepping on a Rake,” it rises above banal clichés — passion becomes an active force, opposing cruelty.

TFS’ approach to rock swings in several directions at once. Their songs swap out moods and tones. Typically, the guitars are coated in deep-fried distortion and fuzz, so much so that they become indistinguishable from keyboards. Because of that, the album’s passages of clean, chiming guitar leap out as relief. “Fairytale Codex” begins and ends quietly, but an agitated passage of acoustic guitar and drums underlines the chorus — “a village in hell is waiting for you.” The band is always in control of its complex musical structures, but it exudes an excitingly anarchic spirit, replicating our contemporary experience of overload.

— Steve Erickson

Jazz

Ivo Perelman has been on the jazz scene long enough that I own a commercially produced VHS tape of him performing in 1990. Despite appearing on an abundance of recordings since then, the now 64-year-old Brazil-born saxophonist has hovered just slightly on the outer edge of wider acclaim — a little too far from the mainstream.

Ivo Perelman has been on the jazz scene long enough that I own a commercially produced VHS tape of him performing in 1990. Despite appearing on an abundance of recordings since then, the now 64-year-old Brazil-born saxophonist has hovered just slightly on the outer edge of wider acclaim — a little too far from the mainstream.

Perelman has recorded with the redoubtable Matthew Shipp, a singular force at the keyboard, on numerous occasions over the years. On Armageddon Flower (Tao Forms), he and the saxophonist cut loose on four spontaneously composed, free pieces that include the fulsome participation of Shipp’s String Trio mates, Mat Maneri (viola) and William Parker (bass).

Fans may remember Shipp and Parker’s time with the legendary David S. Ware Quartet. (Does anyone recall the group playing an afternoon gig in the courtyard of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston years ago?). This disc carries a strong taste of what that ground-shaking duo could do. Perelman and Maneri mostly work at the high end, seeking to summon something within and beyond what sounds like a fertile maelstrom.

“Pillar of Light” begins in a primal basecamp, before energy and agitation kick in. The spiritual resonance evinced throughout the disc is dramatized in Perelman’s plaintive cries. Shipp and Parker set a march pace that calls Maneri forward; he heads for a place that’s tonally above the saxophonist. The band creates a mournful zone, creepy but oddly freeing, that sets the haunting resonance for the rest of the session. Perelman takes command of a final trio section that reaches for a sort of lyricism. Are our musician protagonists still trapped? Or finally free?

“Tree of Life” is equally relentless. Parker’s raw arco work leads to an unsettling trek that paces and pulses along; Perelman explores his upper register, skittering among the tune’s sonic roots and branches.

Shipp maintains the title track’s harmonic structure while Maneri and Perelman squeak and squabble, as if trying to exorcise the memory of composer Alban Berg. A minimal pulse is embraced before the saxophonist jets into a sense of urgency that doesn’t let up until a relatively subdued wind-down.

“Restoration” closes the disc in a more reflective mode, though there are still some tremors and aftershocks. Maneri and Parker plot a nice middle passage that the others disrupt and complicate. Perelman summons up some fantastic free blowing to bring the recording’s quest to its end, with Shipp capping it with a bit of sweetness to make things (almost) all better.

— Steve Feeney

Books

I don’t like cats.

I don’t like cats.

A lot of them make me sneeze.

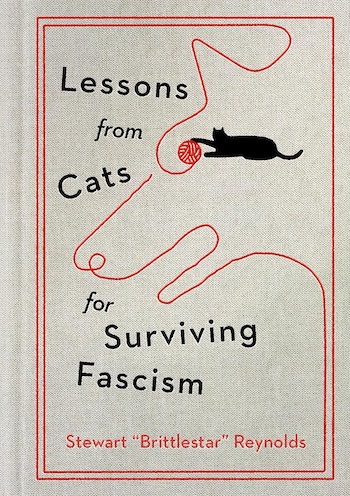

Lessons from Cats for Surviving Fascism by Stewart “Brittlestar” Reynolds (Grand Central Press) is inspired by the behavior of cats. It did not initially strike me as promising.

But these are strange and desperate times. It would be irresponsible to dismiss out of hand any suggestion for surviving fascism.

“Brittlestar” Reynolds, who describes himself as “a social media personality” who is a “self proclaimed expert at making people laugh at life’s absurdities” maintains that cats are unpredictable. They’re likely to stage “a great act of defiance” at any time. We can learn from that inclination that “there is no point in wasting energy on nonsense.” Like cats, I guess, we must never let the fascists know our next move, though I would think they are unlikely to guess it, even if we aren’t careful, since according to Mr. Reynolds, “fascists aren’t exactly the brightest bulb in the Mar-a-Lago chandelier.”

Cats take naps. So should you, if you want to survive fascism, because “nothing terrifies a fascist more than someone who’s wide awake, well rested, and ready to strike.”

The strike is also important. Mr. Reynolds celebrates the ability of cats to extend their claws and scratch when necessary, though it’s my experience that cats sometimes do that when it’s not necessary. Anyway, Mr. Reynolds is in favor of “a well-timed scratch – a cutting remark, a sharp protest, or a biting comedic commentary posted online” as “resistance” that for whatever reason reminds him of cats.

Mr. Reynolds also maintains that cats are good at “solidarity,” though anyone who has witnessed a cat fight might disagree. Anyway, as the media personality writes, “fascists can’t handle solidarity.” More credible than solidarity on the part of cats is the assertion that they are good at disappearing, especially when they have an appointment at the vet’s office. Mr. Reynolds says this, too, is an important skill in the fight against fascism, and there are migrants who wouldn’t argue.

Cat lovers are likely to love this book, which is perhaps what Mr. Reynolds had in mind when he put “cats” in the title. If he’d worked something about weight loss into it as well, he’d perhaps have had a best seller. Me, I’ll now wait for a short book about what dogs have to teach us about the struggle to reclaim due process.

— Bill Littlefield (his most recent book is Who Taught That Mouse To Write, available at writingmouse.com.)

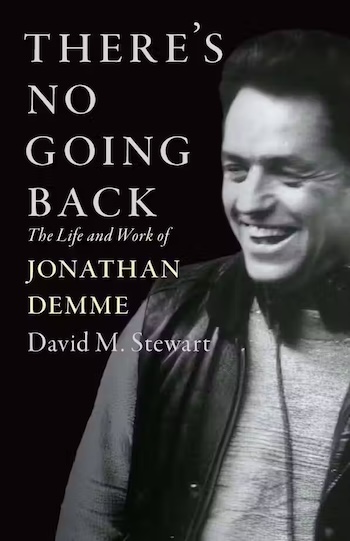

An anecdote early in David M. Stewart’s brisk, comprehensive, and insightful There’s No Going Back: The Life and Work of Jonathan Demme (University Press of Kentucky) epitomizes the kind of character the filmmaker, who died in 2017 at the age of 73, would demonstrate throughout his life.

An anecdote early in David M. Stewart’s brisk, comprehensive, and insightful There’s No Going Back: The Life and Work of Jonathan Demme (University Press of Kentucky) epitomizes the kind of character the filmmaker, who died in 2017 at the age of 73, would demonstrate throughout his life.

Pursuing his early vocation to become a veterinarian, Demme found himself working at a clinic selling blood from greyhounds for transfusions. Appalled, he tried to rescue one of the unfortunate dogs and was fired.

Perhaps this disillusioning incident encouraged him to transfer his focus from this presumably idealistic but occasionally vampiric industry to another not unlike it – the movies. Be that as it may, while attending vet school he started writing film reviews for the student newspaper. His father was friends with mogul Joseph E. Levine, who admired the young Demme’s review of his film Zulu (1964) and offered him a PR job that would eventually take him to Roger Corman, midwife to New Hollywood auteurs, and from there a series of serendipitous connections, defeats, and renewed opportunities, a pattern recurring throughout Demme’s career.

Throughout these ups and downs Demme remained true to his basic decency and humanity. These are the themes, plus an insatiable curiosity and passion for experience, which are the defining marks of his wide-ranging oeuvre.

But as with his early veterinary experience, sometimes his best intentions led to unintended consequences. With his masterpiece Silence of the Lambs (1991) he achieved his goal of creating an iconic feminist hero but in the process offended members of the gay community with the film’s transgender villain. He attempted to rectify that by confronting the AIDS crisis in Philadelphia (1993), only to be chastised by no less than Larry Kramer for its “falsehood.”

But he must have been doing something right because Silence won five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director and Philadelphia was nominated for five, winning Best Actor for Tom Hanks.

Stewart is adept at exploring these ironic reversals and restorations of fortune but, like Demme himself in his best movies, is even more poignant in tracing the details and personalities in the background, those who helped Demme and whom he, perhaps the most loyal and empathetic of friends, helped as well. It is a portrait of the artist as a good man.

Note: Stewart will be at the Harvard Book Store on July 29 with Ty Burr and at the Brattle Theatre on August 16 with Justin LaLiberty for a screening of Swimming to Cambodia.

— Peter Keough

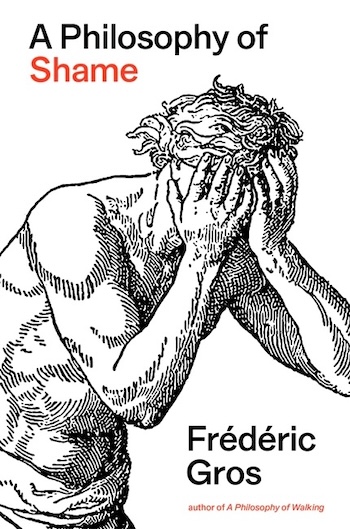

Analyzing Trump’s authoritarian temperament in The Guardian back in February, philosopher Judith Butler wrote that “he defies shame and legal constraints in order to show his capacity to do so, which displays to the world a shameless sadism.” Trump’s shamelessness generates an enormous amount of political clout, exploiting a collective urge to bask in the pleasure of punishing the powerless. And that raises a crucial question for those who are shamed by what they see: is it of any use to feel mortification at Trump’s lack of it?

Analyzing Trump’s authoritarian temperament in The Guardian back in February, philosopher Judith Butler wrote that “he defies shame and legal constraints in order to show his capacity to do so, which displays to the world a shameless sadism.” Trump’s shamelessness generates an enormous amount of political clout, exploiting a collective urge to bask in the pleasure of punishing the powerless. And that raises a crucial question for those who are shamed by what they see: is it of any use to feel mortification at Trump’s lack of it?

French philosopher Frédéric Gros responds with an inspiring “yes” in A Philosophy of Shame (Verso, 157 pages, translated by Andy Bliss), a lucid survey of the manifestations of shame over the centuries that serves as an apt companion volume to 2020’s excellent Disobey!: A Philosophy of Resistance (Verso, 214 pages, translated by David Fernbach). Gros scrutinizes the nature of shame over the centuries, drawing on well-chosen examples from French literature (Balzac, Hugo, Annie Ernaux, Jean Genet) as he nimbly summarizes and categorizes various kinds of shame — triggered by moral or bodily revulsion. He eventually moves beyond the customary type, which is private agony triggered by social disapproval, to a more galvanic, outward-reaching version, seeing it as a kind of “resistance mechanism” that activates when confronted with humanity at its most loathsome.

The takeaway is that many will feel shame at Trump’s (and our culture’s) shameless infliction of cruelty. But by not acting on that sense of mortification, the emotionally despondent will share in the degradation. Gros points out that “Shame is a painful fluctuation between sadness and anger that can have two outcomes: It can lead us down a cold and dark path that disfigures us and ends in solitary resignation, or a fiery and luminous path that transfigures us and fuels collective anger.” One can milk one’s shame at the inhumanity of the world until it curdles, or honestly ask what could have been done to prevent the brutality — and imagine what might be done in the future to stop it.

— Bill Marx

At a moment when all the stories about Israel are dire evaluations of war, readers can take a summer respite with Iddo Gefen‘s Mrs. Lilienblum’s Cloud Factory (translated by Daniella Zamir, 288 pages, Astra Publishing House), a lovingly absurdist depiction of Israel’s Start-Up Nation culture. As the book opens, a Dutch tourist discovers Sarai Lilienblum, who has been missing from her family for three days, wearing a burgundy bathrobe and calmly sipping an ice-cold martini at the bottom of a crater in the middle of the desert. What is she doing there? Well, it turns out that Sarai, who studied aeronautical engineering at the Technion and works as a high school robotics teacher, has rigged up a red vacuum cleaner and invented a device that turns sand into clouds, which in turn makes it rain. Her climatological success has been captured on a video that goes viral on the internet, sparking interest from venture capitalists and a rapt public, with one Instagram user calling her a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci.

At a moment when all the stories about Israel are dire evaluations of war, readers can take a summer respite with Iddo Gefen‘s Mrs. Lilienblum’s Cloud Factory (translated by Daniella Zamir, 288 pages, Astra Publishing House), a lovingly absurdist depiction of Israel’s Start-Up Nation culture. As the book opens, a Dutch tourist discovers Sarai Lilienblum, who has been missing from her family for three days, wearing a burgundy bathrobe and calmly sipping an ice-cold martini at the bottom of a crater in the middle of the desert. What is she doing there? Well, it turns out that Sarai, who studied aeronautical engineering at the Technion and works as a high school robotics teacher, has rigged up a red vacuum cleaner and invented a device that turns sand into clouds, which in turn makes it rain. Her climatological success has been captured on a video that goes viral on the internet, sparking interest from venture capitalists and a rapt public, with one Instagram user calling her a 21st century Leonardo da Vinci.

It’s not like the rest of the Lilienblum family has their feet particularly firmly on the ground. Her husband Boaz and adult son Eli, through whose eyes we see most of the novel’s action, are managing a hostel in the middle of nowhere dotted with ski chalets designed by a Swiss architect no one has ever heard of, and her daughter Naomi, who thought she had escaped to Silicon Valley, is sucked back into the family drama only to find herself generating some alternate facts of her own. And then there’s the mystery of the disappearance of an Irish hiker named McMurphy, a love interest for Eli, and questions about the aspirations of the village’s elderly millionaire widow, Hannah Bialika, who has problems sleeping and steps up to bankroll the transformation of Mrs. Lilienblum’s invention into a marquee business.

The romp is fun, even more so if the reader is familiar with some of the clichés of startup culture in general and Israeli culture in particular (oh, those glasses of fresh-squeezed orange juice!). In some sense, the book is as jerry-rigged as the cloud factory, with one character ping-ponging off another with only the slightest nudge of motivation. Still, this is a story that will put a smile on your face as the Lilienblum family holds a can-do attitude and gullibility in precarious balance, and characters who can’t get anything quite right come to sincere, if grudging, acceptance of the contours of reality. Like the rain in the desert, Mrs. Lilienblum’s Cloud Factory is a surprising, light refreshment.

— Debra Cash

Classical Music

Longtime organist Justin J. Murphy-Mancini and the late Barbara Owen, the recognized scholarly authority on the history of organs in America

A CD review usually shows the front-cover image, which in this case would be a view of the organ in the Newburyport Unitarian Church. But the people behind the recording deserve at least as much attention, so I’m leading with a photo of the church’s longtime organist, Justin J. Murphy-Mancini, and of the late Barbara Owen, who was his predecessor at the church and the recognized scholarly authority on the history of organs in America.

The album’s indiegogo site shows a 3-minute video about the organ’s history, narrated by Murphy-Mancini. Four prominent organ builders built and rebuilt the organ in 1834, 1889, 1957, and, most recently, 2012. This last rebuild largely restored, as much as possible, the instrument’s original qualities while allowing effective performance of works from later generations.

Murphy-Mancini demonstrates this in 74 minutes of music by New England composers. Some of these figures are well known in the wider musical world, such as John Knowles Paine (whose symphonies have been recorded by Zubin Mehta, JoAnn Falletta, and Neeme Järvi) and George Whitefield Chadwick (his Symphonic Sketches are immensely colorful and touching). Also represented are two composers known mainly in the organ world: Dudley Buck and Daniel Pinkham. And we get works by four other twentieth- or twenty-first-century composers: Everett Titcomb, theater organist Edith Lang, David Hurd, and Murphy-Mancini himself. Plus three “voluntaries” (and an arrangement of “Washington’s March”) from the decades around 1700.

The performances are delightful, and very clearly recorded, quite unlike the cavernous, echo-drenched sound on many other organ recordings. I suppose it helps that the church is small or, as architects would say, human-scale.

A thick booklet provides well-researched and insightful essays on each composer and piece, and on the instrument and its history.

Call this an organ program for people who think they don’t like organ music. (To order or to try any track, click here.)

— Ralph P. Locke

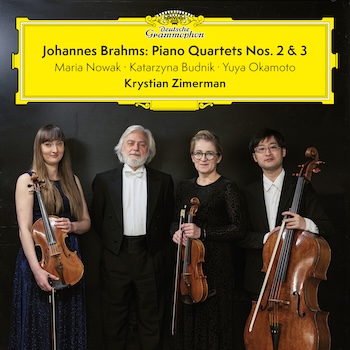

What’s more astonishing: a pair of exceptional performances of repertoire staples or a flawless ensemble? In this new account of Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartets Nos. 2 & 3 (Deutsche Grammophon), you don’t have to choose. You get both.

What’s more astonishing: a pair of exceptional performances of repertoire staples or a flawless ensemble? In this new account of Johannes Brahms’s Piano Quartets Nos. 2 & 3 (Deutsche Grammophon), you don’t have to choose. You get both.

Pianist Krystian Zimerman, violinist Maria Nowak, violist Katarzyna Budnik, and cellist Yuya Okamoto are certainly a dream team. Zimerman may be the star, but he’s an exceedingly collegial one, as the conversational quality of the group’s playing—especially their take on the sunny A-major installment (No. 2)—attests.

In that one, balances, phrasings, tone color, and character are all beautifully and thoughtfully addressed. Just listen to the exquisite textures at the start of the Poco adagio or the punching rhythms in the third movement’s trio. The boisterous finale snaps brilliantly.

The ensemble mines the darker hues of the C-minor Quartet (No. 3) with palpable relish, bringing symphonic weight to their playing whenever it is needed but never turning ponderous. Indeed, the intensity of their reading ensures that the outer movements are aptly tempestuous—the viola’s double-stop sixteenth note figures in the first-movement development are electrifying—and the Scherzo drives with wild urgency.

Meantime the transcendent Andante comes across as a picture of dreamy lyricism. Here, even on an exceptionally fine album, the foursome is at their considerable best, playing with an absorbing mix of delicacy, warmth, and expressive focus.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra during its Mexican tour. Photo: Paul Mardy

Teenagers don’t normally play music by Gustav Mahler. Still, one of last spring’s best concerts was the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra’s March account of that composer’s massive Symphony No. 6.

On June 26, to wrap up their tour of Mexico, the orchestra and conductor Benjamin Zander were joined by members of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México to perform the warhorse in Mexico City’s Sala Nezahualcóyotl. The event, which I caught via stream, can be viewed here.

The fundamentals of Zander’s earlier interpretation remained intact: Thursday’s was a Sixth that drove with purpose and color, striving in defiance of the hammer blows that shadow its huge finale. But it had also grown in subtlety and nuance.

The transitions in and out of the Scherzo’s altväterisch refrains beguiled. The Andante’s phrasings unspooled with easy naturalness and the orchestra’s navigation of Mahler’s opalescent writing in that section was spot-on. Though fatigue emerged intermittently in the finale, Zander’s was a reading that did full justice to the music’s craggy tenaciousness: nothing save oblivion itself stands in the way of the Sixth’s spirit of perseverance and creativity.

On a typical program, the Mahler either stands on its own or is preceded by another work. The BPYO, however, sometimes goes its own way. On Thursday, they followed the Sixth with a pair of selections, Arturo Márquez’s Dánzon No. 2 and “Nimrod” from Elgar’s Enigma Variations.

That choice might not have made the most musical sense. But the former—led by BPYO assistant conductor Alfonso José Piacentini Betancourt—brought down the house, and the Elgar, well, that’s the orchestra’s signature gift of friendship and love. Given the hash the current administration has made of international relations, they were also timely reminders that, even in times of peril, humanity, decency, and goodwill can still transcend borders.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Visual Art

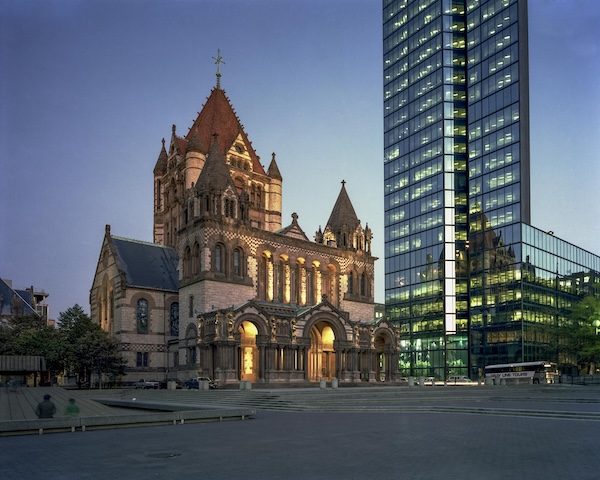

Trinity Church and the John Hancock Tower, 1983, by Peter Vanderwarker

Over five decades, internationally regarded photographer Peter Vanderwarker has illustrated, through his camera, stories about our built environment. His enchanting photos have caught the essence of numerous award-winning architectural projects. Raised in Connecticut, he earned a Bachelor of Architecture from the University of California Berkeley and became a Loeb Fellow at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. He is the author of seven books about Boston’s history, architecture, and man-made structures and spaces..

Reflecting his own affable and winning personality, Vanderwarker’s precise, yet warmly articulated pictures are in many collections, including the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, The Addison Gallery of American Art, the Boston Athenaeum, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, the MIT Museum, and Harvard’s GSD. He has been honored by the American Institute of Architects.

Through his ability to capture, in his images, character, strength, and presence, Vanderwarker has earned a reputation as a preeminent architectural photographer of iconic structures. His photos evoke Boston’s past and present while promising to inspire its future. Introduced to photography as a student at Phillips Academy, Vanderwarker knew early on he wanted to be a photographer. His practical father lovingly told him that he shouldn’t throw away his life to serve that dream. So Peter initially studied architecture. After three rather miserable years in a firm, Vanderwarker worked on anti-war movies and taught architectural design. At the age of 30 he started photographing buildings. Nearly starving (his words), he shot whatever architectural jobs he could get. Because of his teaching, he eventually networked with a lot of local architects, who helped him find work.

A fortuitous meeting with Boston Public Library’s Photographic and Print Curator Sinclair Hitchings led to a collaboration that resulted in the book Boston, Then and Now. He asked the late Robert Campbell, Boston Globe architecture critic, to write the volume’s foreward. This led to their long-running collaboration in “The Boston Globe Magazine” — “Cityscapes of Boston.” In the feature, Vanderwarker’s photos were paired with Campbell’s texts.

Vanderwarker’s work is inevitably about teaching. Viewers can always learn something from his photos, especially if they look carefully at their details, contrasts, and perspectives. These pictures reflect the vivacious personality of their creator; they express a forthright exuberance and charm. So, while there are lessons to be learned, they also celebrate form, color, and material relationships in both the built and natural environments. They inspire joy.

— Mark Favermann

Film

John Malkovich and Émilie Dequenne a scene from Mr. Blake, at Your Service!

I was intrigued by the premise of Mr. Blake, at Your Service!: John Malkovich plays a recently-widowed man who retires from his high-profile career and goes to France to visit the place where he met his late wife. After a series of confusing events, he soon finds himself working as a butler in the gorgeous manor house where he had arrived as a guest. The first thing to know is, this is a French film (written and directed by Gilles Legardinier, based on his novel Complètement cramé!/Completely Burnt Out!), and every character speaks French throughout (Malkovich’s French is flawless and rather impressive in this regard). The owner of the house, Nathalie (played by Fanny Ardant), has also recently lost her spouse. She is struggling to keep the place afloat financially, and is having regrets about her marriage. Head housekeeper Odile (Émilie Dequenne, a fine Belgian actress who died in March 2025) is efficient, brusque, and oddly shocked at how little Blake knows about the duties of a butler. But, like everyone he comes in contact with, Blake charms her with his kindness and gentle affability.

But herein lies the flaw with this finely-acted film, set in a stunning historical landscape. The character of Blake is a mystery. The guy is apparently well-known in London. The first scene has him attending a “Man of the Year” banquet where, just before he is to be honored, Blake slips away, to the chagrin of the organizer and his friend Richard (Al Ginter), another Englishman who prefers to speak French. We never learn what Blake did to earn this honor; we see very little of the protagonist’s life before he arrives in France. Add to that the fact that everyone Blake meets, from the rough gamekeeper Magnier (the wonderful Philippe Bas) to the troubled chambermaid Manon (Eugénie Anselin), becomes his friend and is enlightened by his worldly wisdom. This nonstop likability is compounded by the dialogue’s rather saccharine, Hallmark-style cheeriness. I discovered that this 2023 film (just released in the US) has also been titled Well Done! and At Your Service, Madam, apparently in an attempt to help it find its audience. Despite the beautiful setting and fine cast, Mr. Blake, at Your Service! feels threadbare and rather contrived: Malkovich manages to hold it together with his inimitable talents, but they’re mostly wasted here.

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: "Armageddon Flower", "Fairyland Codex", "Mr. Blake, "Mrs. Lilienblum’s Cloud Factory", "Pantilde", "There’s No Going Back: The Life and Work of Jonathan Demme", Fire Records, Gareth Lilliard, Iddo Gefen, Ivo Perelman, John Malkovich, Jonathan Demme, Justin J. Murphy-Mancini, Matthew Shipp, PRAH Records, Peter Vanderwarker, Tao Forms, The Worm, Tropical Fuck Storm, at Your Service!"