Author Interview: Joan Lancourt on Junior Programs — Pioneers of Theater for Young Audiences

By Bill Marx

Junior Programs undertook “a visionary rethinking of the potential relationship between the performing arts and the lives of the nation’s children, with specific artistic innovations emerging organically from that rethinking.”

More Than Entertainment: Democracy and the Performing Arts (Junior Programs) is the heretofore untold story of Junior Programs, Inc. (1936-1943), a trailblazer in making theater for young audiences (TYA). But the book does more than fill a gap in understanding how America created stage work for children. Author Joan Lancourt does more than identify the critical elements that were responsible for the company’s extraordinary seven years of success. She makes a compelling case that many of those same elements can help today’s TYA practitioners address their most urgent challenges.

Founded in 1936 by Dorothy McFadden, a New Jersey mother disgusted by the violent and racist cowboy and Indian fare emanating from Hollywood, Junior Programs, Inc. became an umbrella for three professional companies — opera, ballet, and drama — that were dedicated to introducing children to the finest cultural offerings from around the world. Because troupes toured throughout the US, Junior Programs provided the first experience of live theater for many in an audience of four million children.

I had several questions for More Than Entertainment‘s author Joan Lancourt, daughter of Junior Programs’ iconoclastic artistic director, Saul Lancourt. What made Junior Programs so special? And could its impressive successes be duplicated — in today’s polarized America?

The Arts Fuse: In what ways did Junior Programs develop the “art of children’s theater”?

Lancourt: For me, art is about a creative process — “art” is seeing something in a fresh, new way, in a way that doesn’t already exist, and then bringing it into being. For Junior Programs, their “art” began with how they thought about the performing arts. Then, as now, the rise of fascism was posing an unsettling threat to democracy. The need to preserve and sustain democracy was very real, and they understood that if the next generation was not well prepared to preserve and sustain it, it was entirely possible that the “American experiment” would fail. From the outset, McFadden and Lancourt believed that performing arts for children could and should be more than entertainment; it was an essential resource for preparing the next generation to be active citizens in a democracy.

At the time, much of what passed as children’s theater was performed by amateur community theaters. Professional holiday productions like Peter Pan on Broadway were rare. A few small regional theaters focused on children, and some “educational theater” involved children directly. Thus, another of Junior Programs’ major contributions to the “art” of TYA was their view that “only the best is good enough for children.” This belief became their motto, and for them “the best” meant touring Broadway-quality professional productions specifically designed for the nation’s youth. Their operas were by world renowned composers (e.g., Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Bumble Bee Prince); their ballets were choreographed by internationally acclaimed dancers Edwin Strawbridge, Ruth St. Denis, and Ted Shawn; reviewers everywhere swooned over their sets and costumes, and the talents of their performers as well as the myriad innovations that had children on the edge of their seats, literally cheering, even for the so-called esoteric forms of opera and ballet.

AF: Theater is not usually seen as serving democratic ideals. How did Junior Programs dovetail children’s theater with learning about citizenship?

Lancourt: Their vision of the “art of TYA” included a Credo that implicitly and explicitly guided their work, embodying democratic ideals: equality, opportunity, freedom of choice, and a free press.

In order that American children may be guided to the preservation of democracy, freedom, and the world’s cultural heritage, and realizing the important influence which recreational habits have on the character and personality development of the child … WE BELIEVE that all American children, regardless of race, creed or social or economic status, should have the benefit of inspiration by the finest professional artists in performances created for youth; WE BELIEVE that these performances should develop their personalities and artistic tastes, and guide them toward democratic ideals; [and] WE BELIEVE that the artistry of all races and nationalities … should be made available to all children … [and] that a press free to evaluate and criticize such entertainments result … in ever higher artistic standards.

As they searched for appropriate material to transform the Credo from aspiration to reality, they were keenly aware of the brewing social, political and economic tensions. The nation was emerging from the Great Depression; fascism was nibbling away at the American democracy; and the clouds of WWII were gathering. They asked: How could the performing arts prepare the next generation to address the tensions in a nation of immigrants, particularly the marginalization of indigenous and immigrant communities of color? They understood that a divided nation would be ill-equipped to win in the coming conflicts.

Program for The Reward of the Sun God. Photo: courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

AF: Can you give me some examples of how they shaped theater that would work against the forces of division?

Lancourt: The five dramatic plays they commissioned ventured into entirely new territory. Eschewing the usual sentimental children’s fare, their first commissioned play was The Reward of the Sun God, a tale that explored the adventures and misadventures of two Hopi Native American children. Run, Peddler, Run was a lively tale of two Colonial-era Irish immigrant children that touched on the issues of indentured servitude and slavery; The Emperor’s Treasure Chest featured a hi-jinx-filled story of Brazilian youngsters intent on solving the mystery of a hidden treasure; and The Adventures of Marco Polo took their youthful audience on an exciting journey from Venice across the Mideast and India to China.

Each production underscored the universality of the human experience, offering a positive assessment of a culture typically maligned by Hollywood films. Sun God stressed the values and strengths of the Native American culture; the portrayal of Brazil highlighted its democracy and the appeal of its music and dance; and Marco Polo acknowledged the many scientific and social achievements of Chinese culture. And their final production, Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A., was their answer to the question, “How do we teach children about the importance of preserving our democracy?” Doodle Dandy blended fantasy and reality to tell the story of early 20th-century Springville, USA high school students who defended their town against a dictator intent on erasing their democracy. That young people themselves had agency was an essential part of the story.

AF: In what ways did this approach to content shape how Junior Programs interacted with the educational establishment?

Lancourt: From the outset, there were deep partnerships with the leading educational institutions of the day (e.g., Columbia Teachers College), and with the frontline teachers of the local schools in the hundreds of communities in which they performed. That connection led to the development of correlated curriculum study units (CCSU) for almost all productions. These resources were sent to the schools three months before the performance, which enabled the teachers to deepen the students’ appreciation of the culture and issues touched on in the show. For Treasure Chest, social studies teachers received a unit exploring the differences between the Brazilian and American forms of slavery; economics classes studied the natural resources underpinning the Brazilian economy; for the ballet, Robin Hood, history class learned about feudal societies; for “phys ed” students practiced the Native American “corn cob” game, or archery; shop provided a blueprint for crafting a Chinese junk; school orchestras received scores so they themselves learned to play the music; English classes discussed Shakespeare in preparation for the ballet The Adventures of Puck, and collectively, the various units for Marco Polo were considered by many to be one of the most comprehensive curriculums on the 13th century.

Program for Pinocchio. Photo: Courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

AF: So the idea was that theater should be able to engage the entire child, the head and the heart?

Lancourt: Yes. The performing arts were a catalyst, a synthesizer, a way to engage in the Deweyan concept of experiential and communal learning. The children were not merely spectators being entertained but were fully engaged: they became learners with agency. For Junior Programs the performing arts were not something separate from life; not something one dipped into occasionally in one’s spare time; a performance pulled all the pieces together into a meaningful whole, one that often sparked further community inquiry.

This organic approach to TYA yielded numerous artistic innovations. Rejecting conventional approaches, they reinvented opera and ballet to meet the needs of young audiences. They maintained the musical integrity, but replaced slow pacing and repetitive arias with engaging, fast-paced action. Their production of the opera Jack and the Beanstalk even featured a beanstalk that grew on stage. Unusual at the time, they explicitly hired singers who possessed significant acting skills; and rehearsals focused not only on the music, but on ensuring the singers brought their characters to life in vivid, nuanced ways. This was enhanced by the decision, also unusual, to sing in English, with the singers’ clear enunciation favorably commented on by many reviewers. For the ballet company, Junior Programs invented what they called the “dance-play.” Adapting a device used for their operas, they commissioned scripts for each ballet. A costumed professional actor narrated from the side of the stage, changing their voice so skillfully that countless reviews tell us that the excited audience of thousands of children believed the dancers themselves were speaking.

AF: In your book, you also note that reviewers commented on the creativity and authenticity of the sets and costumes. Why was that an important feature of the Junior Programs productions?

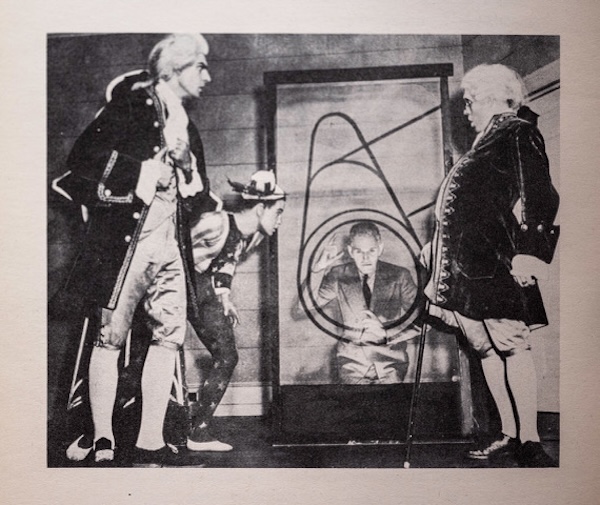

Lancourt: While their definition of authenticity might not pass muster today, Junior Programs viewed their efforts as a sign of respect for the diverse cultures they portrayed. For Sun God, the religious masks of the Hopi gods were meticulous copies of authentic kachina masks; for Treasure Chest, the dances, music, and costumes were developed in close collaboration with the Brazilian consulate; and for the ballet Robin Hood, the music was a synthesis of Margaret Carlisle’s original research in the London archives of medieval music. In the first act of Marco Polo, an almost life-sized gondola glided across the stage, and the Prelude to Act II featured a band of Asian stick puppets moving steadily across an enormous map of the medieval world, complete with dragons and sea monsters at the oceans’ edges; and as the figures moved across the map, the path of Polo’s journey from Venice to China was traced by a series of tiny twinkling lights. However, for their final production of Doodle Dandy, when gas rationing made it impossible to transport elaborate scenery, they turned challenge into opportunity and embraced the then entirely novel technology of projections — and to their surprise, discovered that children’s imagination had no trouble filling in the gaps in the freehand sketches of a barn raising or the seemingly science fiction “Seeograph” that were projected onto a blank backdrop.

The “Seeograph” in the Junior Programs production of Doodle Dandy of the U.S.A. Photo: courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

AF: How important was WWII in shaping Junior Programs (1936-1943)?

Lancourt: The performing arts have never existed in a vacuum, though they may respond to their world in a variety of ways: some respond by diverting people’s attention from the unpleasant realities; others engage with it. Junior Programs was in the latter group. Their ears and their hearts were finely tuned to what was going on, and there is ample evidence that what they heard and saw shaped their approach to what they did. The war was a fight against democracy’s enemy — fascism — and they understood that a lack of solidarity on the home front would sap the strength the nation needed to win the war. America’s history of exclusion and othering was not new; fascism exploited America’s existing inequalities of race, class, and culture. Knowingly or unknowingly, these divisions were aided and abetted by Hollywood’s largely negative portrayals of immigrants and people of color. As advocates for democracy, Junior Programs aimed to provide positive narratives about communities of color marginalized by the dominant white culture.They did this through the plays they commissioned; and several of the choices they made spoke specifically to the country’s growing need for strong alliances –– with FDR’s Good Neighbor policy toward Latin America, and with our need for China as an ally against Japan.

Ultimately, it was WWII that brought an abrupt end to the success of Junior Programs. Once we entered the war, their performers were getting drafted, and with gas and rubber tire rationing, they could no longer transport their scenery. So yes, WWII shaped them. However, I think it’s important to note that despite the patriotism of their mission, their plays managed to avoid the taint of being called propaganda. They were never dogmatic in their approach to the values of diversity and inclusion; their approach was simply to show how interesting and fun other cultures could be, and that the children of those cultures would make fine friends. They saw no need to “label” things, and on the rare occasion when a review applied the propaganda word to Doodle Dandy, it was presented as a compliment rather than a criticism.

AF: How was Junior Programs organized? How much administration did it take?

Lancourt: To deliver productions across the country with a small New York City staff, they created a unique model: a nationwide network of local Sponsoring Committees. These committees were made up of volunteers from all parts of the community — socially minded women, civic organizations, local businessmen, school principals, college and music clubs, dance studios and social and religious service organizations — all committed to providing their community’s children with the wide range of cultural opportunities offered by Junior Programs. Without these thousands of volunteers, Junior Programs would not have been able to function, for it was the responsibility of these committees to organize every aspect of the local production — from securing the venue to selling the tickets; handling all the publicity (window displays related to each production in clothing stores, book stores, music stores, as well as stories and photographs in the newspapers); organizing the buses to transport the children to and from the auditorium, and ensuring the police were there to direct traffic; making sure the venue had all the necessary equipment, providing the ushers and volunteer stage hands; making sure thousands of children were taken to the toilets during intermission, collecting candy wrappers, and making sure no child was left behind when the show was over.

For seven years, these deep roots into the local communities paid off: the community’s sense of ownership of the Junior Programs productions was strong and there were seldom empty seats at one of their performances. But ultimately, supporting the immediate war effort became more urgent than preparing the next generation for democratic citizenship. The Junior Programs army of volunteers were drafted into a different war. Nevertheless, I think there’s an important lesson here for today’s TYA practitioners. We can’t replicate the thousands of volunteers (primarily women) that Junior Programs organized, but if TYA practitioners want the community to support them, they would do well to learn how to grow deeper roots into all the corners of their local communities.

The archers in the Junior Programs ballet production of Robin Hood. Photo: courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

AF: Children’s theater is often stereotyped as sentimental or saccharine — how did Junior Programs combat that impression?

Lancourt: I don’t think it ever occurred to them to think of TYA that way. I’ve already commented on their view of the role of the performing arts as more than just entertainment. Their mission was preserving our aspirational democracy, and offering sentimental, saccharine fare would never have gotten them where they wanted to go. To be sure, their work was entertaining; without that, they would not have been able to hold a child’s attention. But through the plays they chose, and the educational partnerships they developed, they made it very clear that they were after far more. For them, it was not about cutting adult theater down to a miniature size, in the way primitive portraits of children show us mini-adults. Rather, it involved a visionary rethinking of the relationship between the performing arts and the day-to-day lives of the nation’s children.

AF: It seems to me that Junior Programs dissented from the conventional understanding of children — how they thought and felt. Would you agree?

Lancourt: 100 percent. Their approach to children was Deweyan to its core. For Dewey, the artistic experience was a vital part of everyday life, and he sought to involve the whole child in an experiential, communal, and aesthetic way of life. From first to last, Junior Programs did not see its youthful audiences as merely spectators: numerous scripts included actors posing direct questions to their audience — and waiting for their answers.

We also see this in the way so many of their productions encourage and demonstrate their youthful character’s sense of agency — be it Hansel pushing the wicked witch into the oven in Hansel and Gretel, or the group of high-school students banding together in Doodle Dandy to save their town from a dictator. Numerous performers frequently spoke admiringly of their audiences’ honesty; and in return, review after review mentions that Junior Programs playwrights and performers never talked down to the children in the audience. The mere fact that reviewers so often called this out for praise suggests that Junior Programs differed from those of others actively engaged with children. No matter where you enter into the Junior Programs world, you encounter the respect everyone had, the sense of palpable pride they felt in working with and for children. Not once in all my research did I come across any sense that they felt in any way less professional than performers in adult theater.

Kenneth MacClelland’s set for Act 1 of Marco Polo. Photo: courtesy of Jerold Lancourt

AF: A recent NEA study on Children’s Theater in America has nothing to say about how children’s theater can play a role in inculcating democratic values. Despite its success, why did Junior Programs exert so little influence?

Lancourt: When Junior Programs closed, they gave all their papers and records to the Drama Department at the New York Public Library, and everyone moved on to other lives and other employment. Why no one tried to re-form the company after the war is now a question impossible to answer at this late date. But with key players scattered, their remarkable story was lost, and by the ’50s, when children’s theater regained visibility after the White House Conference on Children, the focus was firmly on the future. It wasn’t until after my father died and I was going through his albums that I remembered him telling me about giving their papers to the NYPL. Having been involved with the theater myself as a board chair of two local theaters, I was curious enough to write to the library and ask if they still had the Junior Programs papers. They did — 13 boxes of them, and once I had gone through them, I knew I had to write their remarkable story.

AF: What is the most important lesson that Junior Programs has to teach children’s theater today?

Lancourt: Well, there is no one magic bullet. The final chapter of the book describes their legacy in eight interdependent sections, But, if you press me, I’d say something like Think “More than Entertainment.” Think partnerships! With educators in all disciplines. With your community! Dig deeper into your communities, and don’t sell — listen.

Our democracy is facing a severe challenge, and we don’t have an FDR to lead the way, but I believe most people want to preserve our democracy — and our diversity. The real question for TYA today: how do we tap the almost limitless potential that the performing arts offers to instill in the next generations a set of values and beliefs worthy of our democratic aspirations? With the defunding of our public schools, with the elimination of the arts and civics from the curriculum, will the next generation even have democratic aspirations? To my knowledge, there is not a public school system in this country that reflects the Junior Programs belief that “Only the best is good enough for children.”

During a time of nationwide tension and conflict — not unlike what we are experiencing today — their innovative use of the performing arts delivered that message from coast to coast. Their documented successes offer today’s TYA practitioners the opportunity to pick up the fallen baton, to use the performing arts to revive our democratic aspirations and recommit to all that that implies. The story of Junior Programs is really a story of hope and possibility, and of a belief in our collective commitment to create a future that builds on the richness and creativity inherent in our diversity.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

This is a fabulous and very important discussion about an equally fabulous and important book. With great attention to detail Joan Lancourt has not only brought alive the crucial part theater can play in the education of our children. She has also given us a template for the future. School administrations, teachers, community centers, chambers of commerce, and arts organizations should read this book carefully and get to work to replicate TYA to help our children develop not only performance skills but also understand the value of our precious democracy.

Kudos to Lancourt for this terrific book!

Phenomenal interview. I am reading this book and it is incredible in its details and insights. The values-based work of Junior Programs guided its wonderful work. We need such programs now.

Joan Lancourt has done today’s practitioners a valuable service with her book More Than Entertainment. Junior Programs did amazing work in cooperation with public schools, on a private budget. It deserves to be used as a model.