Classical Album Reviews: James Ehnes performs Lalo, Saint-Saëns, & Sarasate and Benjamin Schmid plays Gulda & Weill

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Violinist James Ehnes and the BBC Philharmonic supply some truly great performances; violinist Benjamin Schmid revels in composer Friedrich Gulda’s freewheeling sense of play.

Here’s a recording of a type that doesn’t get made that much anymore — and played by just the violinist you want to hear in such fare. That would be James Ehnes, who goes to revisit some of the bread-and-butter of the late-19th-century violin repertoire, in particular Eduardo Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, Camille Saint-Saëns’ Violin Concerto No. 3, and Pablo de Sarasate’s Carmen Fantasy.

The Lalo largely benefits from Ehnes’ urgent, no-nonsense approach. Everything in the outer movements dances with abandon. While there may be a bit too much vigor in the Scherzando and Intermezzo — Itzhak Perlman’s 45-year-old account of the last is more pleasingly sultry — the precision of Ehnes’ playing, not to mention the taut, lean accompaniments the BBC Philharmonic and conductor Juanjo Mena provide, have much to recommend themselves.

Saint-Saëns’ 1880 hit also shines in the younger violinist’s hands. Ehnes makes much of its fireworks: the first movement’s nonstop arpeggios and runs are both thrillingly precise and smartly shaped. So, too, the Andantino’s elegant turns of phrase and the finale’s stormy passions.

Impressive and clean as Ehnes’ reading is, Mena and the Philharmonic make an unexpectedly powerful case for Saint-Saëns’ often luminous accompanimental writing. The music’s subtle plays of color — like the finale’s muted string chorale and the composer’s discreet scoring for woodwinds — result in a performance of real character and style from all involved; the anticipations of the “Organ” Symphony (which came along six years later) ring heroically.

As it happened, Sarasate was the dedicatee of Saint-Saëns’ Third Concerto (he also played its premiere) and his fantasy on themes from Bizet’s opera, which appeared in 1881, has kept his name before the public. The music’s demands are considerable and it’s a testament to Ehnes’ conception of the score as being more than a flashy showpiece that its acrobatics — the stratospheric noodling, reams of multiple stops, artificial harmonics, left-hand pizzicato runs, and more — don’t end up becoming the story of his larger performance.

They’re brilliantly done, for certain. Yet it’s the partnership between Ehnes and the Philharmonic that gets this reading to click. There’s no question that Sarasate’s orchestral writing is subsidiary to the solo part. But when everybody locks in rhythmically and coloristically, as they do here, the sum of this music’s parts exceeds its whole.

Perhaps, then, a larger message of trust, goodwill, and collaboration being the better way to go are to be drawn from this disc. Either way, these are some truly great performances.

When should a cello concerto be repurposed for violin? Maybe when it’s by Friedrich Gulda.

When should a cello concerto be repurposed for violin? Maybe when it’s by Friedrich Gulda.

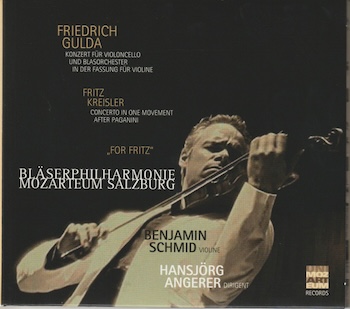

The eccentric Austrian pianist-composer’s 1980 score for cello and wind orchestra isn’t exactly part of the repertoire’s mainstream, but, like most of Gulda’s music, it boasts a devoted cult following. Count Benjamin Schmid a fan. The Vienna-born violinist’s latest recording pairs his revision of Dr. Selim Giray’s transcription of the original with Kurt Weill’s Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra, plus a pair of short, unaccompanied encores.

Given the breadth of Schmid’s musical interests, it’s no surprise that the fiddler makes an excellent advocate for Gulda’s wacky blend of rock, jazz, Austrian folk music, village parade tunes, and avant-garde impulses. Playing what he calls a “semi-electric violin” tricked out with a bridge mic and, from the sounds of things, a distortion pedal, Schmid navigates the extroverted “Ouvertüre” with no shortage of panache.

The cadenza exhibits a zany, jazzy vibe that perfectly suits the music, while the “Idylle” and “Menuett” that frame it sing and dance drily. Though the final march sounds a shade cartoonish, its frantic atmosphere captures something essential about the improvisational madness of the larger score.

Hanjörg Angerer draws accompaniments of spirit and feeling from the Salzburg Wind Philharmonic. The electric guitar and percussion section’s execution of the funk-driven sections in the opening movement are conspicuously spunky.

In this context, Weill’s 1924 score comes over as a more-or-less conventional concerto—which has to be a first for this curiosity. Certainly, the piece sounds like little else: its singular instrumentation, plus the composer’s deliberate adoption of atonal elements and his constant varying of materials, provides an unsettledness one associates more with the Second Viennese School than the future composer of The Threepenny Opera.

Schmid’s unamplified performance here channels the pure acidity of Gidon Kremer. He’s got all the notes and doesn’t shy away from the music’s grittier aspects, particularly in the Notturno and Cadenza.

Angerer and the Philharmonic revel in the Concerto’s unpredictability and hardly stint on color and energy. The acerbic moments that anticipate Weill’s later collaborations with Brecht and on Broadway (like the Notturno’s turns of phrase and the opening of the finale) come out well, though there are also periodic balance issues between the winds and the soloist.

Naturally, no such issues emerge in the solo filler, Schmid’s own “For Fritz” and his arrangement of Weill’s “Youkali.” Though the sonics on each are on the dry side, both selections neatly echo the rest of the album’s freewheeling sense of play.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: BBC Philharmonic, Benjamin Schmid, Chandos Records, Gramola, James Ehnes