Arts Commentary: Art, Music, and the New Age of Anxiety

By Jonathan Blumhofer

However late the hour and however long the road ahead, the cause of standing for justice, knowledge, and freedom isn’t yet doomed. Along the way, let the arts comfort, inspire, instruct, and help lead. That’s what they’re here for.

Wilhelm Furtwängler conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in 1935 with prominent Nazis in attendance. Photo: Wiki Common

The Shadow of History: Furtwängler’s Final Performances

When he took the podium in the Golden Hall of Vienna’s miraculously intact Musikverein on January 28, 1945, Wilhelm Furtwängler likely had some inkling that time was not on his side. Though he’d never been a member of the Nazi party and his relationship with the Führer was equivocal at best, Furtwängler had long been regarded as Hitler’s favorite conductor. But in the short duration of the thousand-year Reich, the maestro had made powerful enemies, among them Heinrich Himmler. Now, in the waning months of World War II, the SS chief was seeking to settle personal scores.

How aware Furtwängler was of his personal danger is an open question, and how much these circumstances imprinted themselves on his musical interpretations of the time is impossible to know. Regardless, that Sunday, he led the Vienna Philharmonic in what proved to be his penultimate concert of the war years.

The program consisted of two pieces: César Franck’s Symphony in D minor and Johannes Brahms’s Symphony No. 2. Taped for radio broadcast, the performance has been preserved for posterity, and what a document it is, particularly the Brahms.

On this afternoon, the German symphonist’s most serene essay followed, to a point, the Furtwängler norm. Tempos and phrasings were flexible, the unblemished radiance of the first two movements sounding astonishingly transcendent, especially given the context of this performance. Throughout, though, the interpretation is held together by a subtle undercurrent of electricity, which explodes in the finale. Here, some of Brahms’s most utterly joyful music drops its mask and takes on, at the end, a completely new cast: the Philharmonic sounds as though it’s playing for its very life.

In a sense, it was. Around this time, Furtwängler advised the orchestra’s members to stick together when the Russian army arrived in Vienna. When that happened in March, they did — and were quickly put to work providing music for the conquering Soviet forces, in the process surviving worse individual fates.

By that time, the conductor was also safe. Tipped off by Albert Speer that he was about to be picked up by the Gestapo, he escaped to Switzerland in early February. His life spared, Furtwängler’s postwar career and posthumous reputation were, however, clouded in ignominy.

Furtwängler and his Brahms performance have been on the mind of late as the balance of power has shifted in our nation’s capital and a neo-authoritarian lurch seems imminent. Granted, leaning too heavily into comparisons between past and present can be a risky business. But sometimes the effort can’t be helped.

In the years leading up to WWII, the Schauspielhaus Zurich became the last free German-speaking theatre. From 1933 on, German emigrants dominated the stage, transforming it into a kind of antifascist “safety zone.” Above is a scene from a 1939 production of Calderón’s The Great Theatre of the World, cast with actors exiled from Germany. Photo: Richard Schweizer/Stadtarchiv Zürich

Now is one of those times. Elon Musk and his tech bros bankrolling last year’s Republican campaign, for instance, had more than a whiff of Gustav Krupp, Fritz von Opel, and other Teutonic industrialists banding together to fund the Nazis’ 1933 seizure of power. The threat that the US government is building, essentially, concentration camps for undocumented immigrants — and prisons in El Salvador holding deported US citizens — is terrifying, as are suggestions from some now in power that court rulings contradicting a President’s executive orders should simply be ignored. With each day bringing new troubles and concerns, how should we proceed?

Ideally, with boldness, though that quality seems to be in short supply, especially in the arts world. What a far cry from 2016 when, within hours of the shock Election Day result, Toni Morrison’s quote that “this is precisely the time when artists go to work — not when everything is fine, but in times of dread” started making the rounds. Eight years on, complacency and resignation seem to be the order of the day.

Considering last November’s result, perhaps that’s to be expected. The American people weighed their options and made a clear-eyed choice. They knew — or think they know –what they’re getting. Unlike the last time, there’s no question whether 2024 was an aberration or not.

But while the electorate’s verdict may give temporary sanction to questionable policies, it doesn’t make right violations of what our 16th president invoked as the “natural law.” Villainizing the “other,” demonizing immigrants, discriminating against the poor and needy, curtailing LGBTQ rights, ignoring the climate crisis, gutting ethical standards for public officials and protections for the general population — these and more have all been done before. As we should know by now, they entail deleterious consequences if left unchecked.

The Role of Art in Turbulent Times

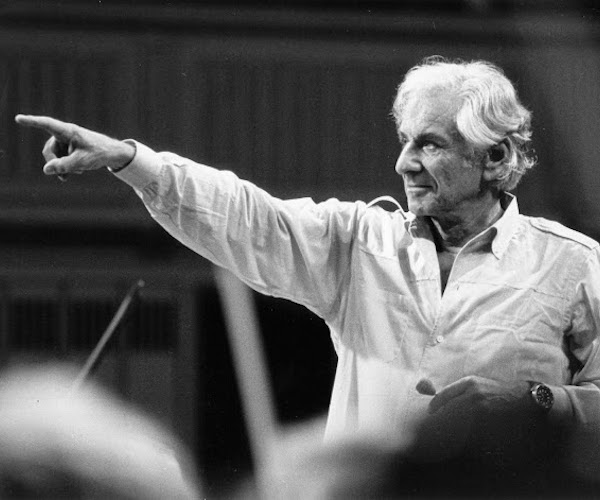

Leonard Bernstein conducting a performance of Candide. Photo: Operalia

What, then, if anything, have the arts got to say to the moment? Is there any right way to fight this repression? Or do such efforts amount to little more than shouting into the void?

When it comes to classical music, particularly, the idea that the genre can speak to the moment in purposeful, moral ways may strike some as surprising — if not outright ludicrous. After all, this art form is hardly part of the cultural mainstream and stereotypically appears as the disposable plaything of the rich and powerful, not the masses.

On top of that, music — of any style — is not policy. It doesn’t write legislation, enforce the law, or set immigration quotas. No symphony or power ballad is going to get Congress to grow a spine and assert its Constitutional role as a check on an out-of-control Executive.

Be that as it may, this niche field has more than a few relevant things to say to our times. Certainly, many of its most noted practitioners held views that resonate with its urgent demands; often enough, these are reflected in their music.

The esoteric customs of Mozart’s freemasonry may remain obscure and unfamiliar. But that movement’s emphasis on reason, fairness, and justice permeate various of the composer’s mature works, most notably Die Zauberflöte.

Similarly, Beethoven, despite the aristocratic airs he occasionally appropriated, was fundamentally a republican of the 19th-century mold, opposed to monarchy and broadly supportive of what Abraham Lincoln would later describe as “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” The finale of his Ninth Symphony gives voice to some of these sentiments, though Beethoven’s greatest hymn to justice and equality came some 20 years earlier in the form of his only opera, Fidelio. In it, the political prisoner Florestan — incarcerated for exposing the corruption of the prison governor, Don Pizarro — is rescued from certain death by the courage of his wife, Leonore, and the timely arrival of the righteous minister Don Fernando.

Examples don’t just come to us from the far distant past.

Leonard Bernstein lent his name and image to all manner of causes, mostly progressive, and never shied away from making big statements, either spoken or musical. True, these were sometimes embarrassing and periodically contradictory.

But the caricatures that grew up around him belied Bernstein’s often deep engagement with the details of the issues at hand. Take his most controversial composition, Mass. For all the distractions its alleged moments of sacrilege provoke, this is a score in which a Jewish secular humanist demonstrates a firmer grasp of biblical commands to put faith into action and for individuals to act as peacemakers than most Christians do.

Audra McDonald in the final moments of LA Opera’s 2007 production of Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Photo by Robert Millard.

Meanwhile, Kurt Weill’s critiques of capitalism’s excesses and injustices with Bertolt Brecht also date from living — albeit barely living — memory. A small body, covering just six years and a half-dozen major works, those efforts remain timely and trenchant, especially their 1930 masterpiece, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.

Set in a boomtown someplace in the imagined American West, Mahagonny is a place where anything goes — except a lack of money. In its final act, as one of the lead characters, Jim, awaits trial, a murderer is set free. Jim, however, is sent to the gallows for not being able to pay his bar tab.

The Challenges Facing Arts Institutions Today

Perhaps Andris Nelsons will see fit to add Weill and Brecht’s indictment of the love of money to his repertoire with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the next year or two. Maybe Boston Lyric Opera will do the same.

Or maybe not: the big money that funds these cultural apparatuses tends to ensure that their institutions remain impervious to change, not to mention averse to embracing social agendas the more sensitive among their number (or ours) might deem objectionable. At the very least, these attitudes encourage the fundamental conservatism of the nation’s major institutions.

They’re aided by audiences and donors who generally — though not always — prefer safe and familiar to challenging and provocative. Yet while the comfort to be derived from the music of Schubert, Brahms, Debussy, and others is as necessary today as ever, to only find safe haven in the repertoire means, often enough, to miss its larger point.

Leo Tolstoy and Maxim Gorky in 1900. Both writers would agree — in different ways — that art serves a didactic purpose. Photo: Wiki Common

Historically, those who control the levers of power — even the most low-born among them — have intuited this, often more readily than their more enlightened peers. In a 1946 Q&A with his apparatchiks, Josef Stalin cited Tolstoy (“not for nothing did Lev Tolstoy say that art and literature is a strong form of indoctrination”) before going on to declare that “there is no art for art’s sake. There are no and cannot be ‘free’ artists, writers, poets, dramatists, directors, and journalists standing above a society. Nobody needs them. Such people don’t and can’t exist.”

Why the menacing, fearful tone at the end? Perhaps because the dictator understood on some level Aristotle’s maxim that “the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.” Hence the Soviet Union’s slippery definitions of acceptable art. Hence the Zhdanov Decree. Hence the repeated purges of dissident artists (and many others).

Stalinist Russia is, thank goodness, a far cry from where the United States stands at the beginning of 2025. There’s no guarantee — as yet — that that’s where we’re headed. Even so, the speed with which rights long taken for granted (like the right to free expression) can erode, especially in the face of an aggressive, antidemocratic agenda like Project 2025 coupled with a reactionary Supreme Court and an impotent, demoralized opposition, provides more than a little cause for concern.

Mencken’s Critique: American Values Then and Now

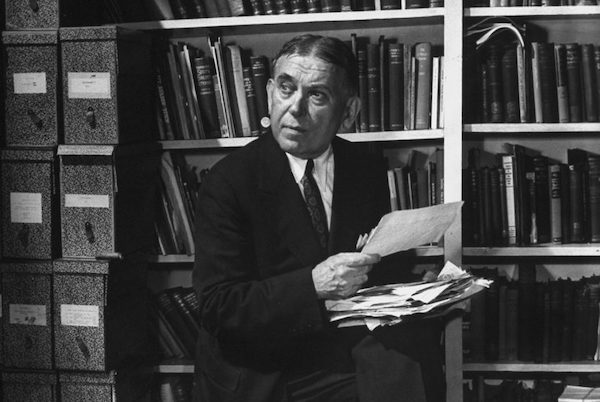

Gadfly H.L. Mencken: “Hallelujah, the desire of America’s plain folks has been granted.” Photo: Wiki Common

H.L. Mencken likely wouldn’t be surprised at our current predicament. “Third-rate men,” the Sage of Baltimore bemoaned in a 1922 essay, “exist in all countries, but it is only here that they are in full control of the state, and with it all of the national standards.”

One can only imagine what Mencken would have had to say about Trump. But the late slide in civic values is nothing new. In the same article, Mencken offered an assessment of “the normal Americano” a hundred years back. It’s one worth quoting at length:

He likes money and knows how to amass property, but his cultural development is but little above that of the domestic animals. He is intensely and cocksurely moral, but his morality and his self-interest are crudely identical. He is emotional and easy to scare, but his imagination cannot grasp an abstraction. He is a violent nationalist and patriot, but he admires rogues in office and always beats the tax-collector if he can. He has immovable opinions about all the great affairs of state, but nine-tenths of them are sheer imbecilities. He is violently jealous of what he conceives to be his rights, but brutally disregardful of the other fellow’s. He is religious, but his religion is wholly devoid of beauty and dignity.

Depressing though the inevitable, Thucydidean conclusion appears — that, despite the ebbs and flows of the last 10 decades, we’re back where we started, spiritually and intellectually — the fact stands that art and music speak to all of those exasperating contradictions. That they haven’t healed or purged them from the national spirit is hardly the indictment some might suppose. In fact, recognizing as much suggests that some definitions — of what art and the practice of it (“the arts”) is and isn’t, and what can reasonably be expected from them — are in order.

First, as I noted earlier, art is not policy. It does not, at least as normally constituted, feed the hungry, shelter the unhoused, or clothe the indigent. To complain, as some do, that because art doesn’t fulfill these necessary social obligations it’s little more than a disposable frivolity, is to completely miss the point: art is not meant to do any of these things.

The second big misconception about art’s purpose is especially pervasive in music. Like many things, this can be summed up by a hard-to-define German term, Bildung. The essential idea of Bildung is that culture has a purifying, elevating effect on a person’s character, and through that, on the larger community. Widely embraced in 19th-century Europe, the notion was — or at least should have been — killed off by the 20th century’s two world wars.

Yet it’s hard to shake, in part because it overlaps with Western ideas about the relationship between morality and art that go back to at least Ancient Greece. That one’s a sticky subject, and it leads into any number of intellectual cul-de-sacs while entirely avoiding easy solutions.

As far as music goes, what do we do with loathsome people who happen to have been great artists? Do we shun Wagner on account of his vile antisemitism? How about Stravinsky (on the same charge)? What is one to make of Richard Strauss and his dalliances with the Nazis? Or Handel and his portfolio that included profits drawn from investments in the 18th-century British slave trade? How about the wider legacy of silenced voices — of women and artists of color?

There’s no way around the tension these questions and similar ones provoke: the distance between the ideal works of human hands and what “the gentlemen of God” (as Mencken once styled them) call Man’s Fallen Nature is often real. Sometimes it’s crippling. But it’s an issue we’ve got to face head-on, in part because if we wrestle with it seriously and well, those contradictions end up getting us where we need to go, to wit: pondering — and pondering deeply — matters of real import.

And this, if I can define such a large subject so succinctly, is the chief object of art: to get one to think, ideally in new, transformative ways. This isn’t, at least in its purest form, politically motivated; rather, it fulfills a human necessity, presenting the voice and perspective of another — sometimes the Other.

To accomplish this, the arts function on multiple levels. They soothe the soul and offend the eye. They enchant, dazzle, frustrate, and provoke — sometimes all at once. But, above all, they aim to engage the critical apparatus while giving voice to the dreams, disappointments, realities, and fantasies of the human experience.

This is why Stalin feared artistic freedom and sought its control. This is why the free exercise of artistic expression is so vital to a healthy society. This is why public-school arts education is so important. This is why artists have an imperative, despite any personal shortcomings, to prophetically speak truth to power. This is why, when an administration seeks to silence and sweep away any and all things it finds objectionable, well-intentioned and civically minded artists and institutions have a responsibility to stand up and make some noise.

Theater as a Platform for Political Commentary

Michelle Trainor as Mrs. Peachum in the Boston Lyric Opera’s production of The Threepenny Opera. Photo: Lisa Voll.

The most natural place to do this is in the theater, and there’s no shortage of examples of stage works either speaking truth to power or channeling the moment. Remarkably, several potent models come to us from the 1920s and ’30s.

One of them is George and Ira Gershwin’s first political satire, the 1927 flop Strike Up the Band! Its daffy plot skewers the United States’s motivations to involve itself in World War I: in this tale, punitive tariffs on cheese lead to a war with Switzerland that’s underwritten by big business. Silly and absurd? Absolutely. Frighteningly resonant nearly a century on? You bet.

The next year in Berlin, Brecht and Weill unveiled The Threepenny Opera. An update of John Gay’s 18th-century critique of the living situation of London’s poor — now with a Socialist tinge — the show spawned a number of hit tunes, including “Mack the Knife” and “Pirate Jenny,” in the process highlighting the absurdities, still very much with us, of society’s treatment of much of the 99% percent.

A decade later, Marc Blitzstein — whose 1953 English-language translation of The Threepenny Opera revived that work’s fortunes — brought Brechtian sensibilities directly into American musical theater with The Cradle Will Rock. Again, greed, corruption, and hypocrisy underline an allegorical tale in which, at the end, an oppressed majority rises up to assert itself.

The world of instrumental music is necessarily more abstracted, its interpretations more varied: after all, Hitler and Churchill both appropriated Beethoven during World War II. Yet, peel away the layers of tradition and complacency that shroud much of the repertoire and even the most familiar of it — the symphonies of Mahler, the piano sonatas of Brahms, the string quartets of Haydn — takes on new meaning and perspective.

At the same time, there’s plenty that’s been written since 1945 that speaks to the anxieties of our shared recent past, though much of it flies under the radar.

Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s output, for instance, has been all but neglected since his death in 1963. But this Munich-born composer, who spent the years of the Reich undergoing what he called an “internal exile,” potently channeled the tumultuous experiences of his life into his music. Some years ago, I wrote about his seething Symphony No. 6, a two-movement essay dating from the early ’50s that packs a world of terror and beauty into only 25 minutes. It’s music that’s well worth seeking out, as are other Hartmann scores, like the Concerto funebre and Piano Sonata No. 2.

Likewise vital is Frederic Rzewski’s mammoth set of piano variations, The People, United, Will Never Be Defeated. Based on a revolutionary Chilean anthem, the piece is, on the one hand, a virtuoso tour-de-force that might be rightly regarded as the first and last word in 20th-century keyboard technique.

But, much more than that, it is an absorbing, sweeping deconstruction of a song about the masses banding together and, collectively, creating a better life. After taking apart its strands, Rzewski rebuilds them, as it were, brick by brick. The imposing edifice that emerges at the end seems inevitable and sounds impregnable.

Important as examples from the past are, our day ultimately requires a body of music from artists that continues the tradition of boldly speaking to the time. In recent years, some of those who have proven most successful in this have hailed from two populations that have, historically, been sidelined by the classical music establishment: women and composers of color.

It’s still too soon to say if the effort begun in the late 2010s to belatedly address the systemic neglect of composers like Louise Farrenc, Amy Beach, William Grant Still, Florence Price, George Walker, and others is going to stick, or if, in another year or two, the enterprise will peter out. Those names (and others) are increasingly before the public, their music increasingly recorded and by leading individuals and groups, not just those of the second or third tier.

Programming, though, remains a touchy issue, whether in Boston, New York, or Chicago. Too often, a novelty aspect prevails and this repertoire is isolated: either shunted off to a single concert or lumped all together for one weekend in a season. It’s good to hear this stuff, the thinking seems to go, but heaven forbid it rub elbows with Beethoven or Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky or Copland.

But, like most things of value, this fare benefits from just such associations, as the BSO’s 2023 pairing of Carlos Simon’s Four Black American Dances and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 attested. Far from being overshadowed by the older work, Simon’s opus more than held its own, the contrasts between his style and Beethoven’s emphasizing just how much the younger composer had imbued these seemingly “light” musical idioms with serious musical content.

One of the most commendable things about Simon and his generation — composers like Jessie Montgomery, Allison Loggins-Hull, and James Lee III, as well as performers like Randall Goosby, Davon Tinés, and Julia Bullock — is their willingness and ability to fulfill the role of the citizen-artist. To attend a recital by Tinés or Bullock means, for certain, to experience first-rate music making. But their programming is even better, often giving voice to the past in ways that powerfully echo in the present.

Simon and several of his colleagues also write music that responds directly to our times. This can be a tricky needle to thread: the list of canonic repertoire composed in reply to current events in any era is awfully short. But when it’s done carefully (as in, say, Richard Strauss’s Metamorphosen), the results speak for themselves.

That’s the case with several of Simon’s compositions, such as Requiem for the Enslaved — a meditation on the 1838 sale of 272 enslaved men, women, and children by Georgetown University (where the composer now serves on the faculty) that draws on Spirituals, Catholic liturgy, and the spoken word — and An Elegy: A Cry from the Grave. The last was written in response to the murders of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Michael Brown, and continues the tradition of the American instrumental lament that goes back at least to Barber and Walker. Mournful and reflective but not despairing, its unsettled chromaticism recalls Brahms but avoids predictable resolutions.

There’s no shortage of more overtly political efforts, either. Loggins-Hull’s Homeland, for instance, ruminates on the composer’s experience of feeling like a stranger in her own country, at one point offering a distorted quotation of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Then there’s Julia Wolfe, whose subject matter often traffics in familiar totems from the national mythology: Steel Hammer (based on John Henry folklore), Anthracite Fields (coal mining), Fire in My Mouth (the aftermath of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire), Her Story (women’s suffrage). In the process, Wolfe’s rock- and minimalist-influenced language brings the past’s timeless themes into the present, often hauntingly and dramatically.

Boston’s Arts Institutions Can Embrace the Challenge

As it happens, Boston’s big musical institutions are well poised to meet the moment, if they choose.

Simon is the BSO’s Composer Chair and Andris Nelsons has shown a clear interest in both presenting the music of our time and advocating for up-and-coming composers. What might happen next could be a more thorough-going thematic integration of old, new, and unfamiliar. How about, say, William Grant Still’s “Afro-American” Symphony paired with some Shostakovich? Or Jessie Montgomery and Anna Clyne sharing an evening with Haydn?

Better: bring artists like Bullock and Tinés to Symphony Hall and have them curate programs with Simon, Nelsons, and the orchestra, like what Esa-Pekka Salonen began at the San Francisco Symphony before that institution faced a major financial crisis. The BSO seems to be in stronger fiscal shape. With Chad Smith now settled in at its helm, why not strike out and try something fresh?

Then there are the city’s scrappy opera companies.

White Snake Projects music director Tianhui Ng in action. Photo: Kathy Wittman

Both Boston Lyric Opera and White Snake Projects have, in recent years, engaged aggressively with timely concerns. The latter, which styles itself as Boston’s “activist opera company” has carved out a particularly notable position as an incubator of new works. Sometimes goofily and whimsically, but always with vigor and purpose, the troupe has embraced its mission, recently announcing a new season that focuses on the climate crisis.

BLO’s reckonings with questions of identity, appropriation, and gender in the standard canon have met with mixed results. Even so, the company’s willingness to boldly address these issues is admirable. Like WSP, their upcoming March offering contends with environmental concerns, this time via the music of Antonio Vivaldi.

Though their offerings are fewer and farther between, Odyssey Opera’s programming regularly touches home, too. The company’s October 2024 presentation of the other two Gershwin political satires — Of Thee I Sing and Let ’em Eat Cake — could hardly have come at a better moment. Similarly, Odyssey’s 2023 production of Tobias Picker’s Awakenings hauntingly brought to life questions of medicine, science, and ethics.

And let’s not forget smaller local ensembles: chamber groups, choral assemblies, new music ensembles, and the like. The Cantata Singers, for instance, recently announced a March program focusing on the climate. And, a bit further afield, the Worcester Chamber Music Society is offering a Black History Month concert that includes music by Simon, Loggins-Hull, Lee, and Adolphus Hailstork.

For the most part, these efforts haven’t been of the tub-thumping variety. And maybe they mostly needn’t be: the Boston Symphony’s recent traversal of the complete Beethoven symphonies offered plenty of opportunity to draw philosophical and extra-musical conclusions. But it did that without any assisted guidance from the podium or the program booklet.

When such things are needed, though, Boston’s blessed to have a conductor like Benjamin Zander. His eloquent spoken introductions to the music he conducts with the Boston Philharmonic (most of it firmly canonical) illuminate details and contexts that might otherwise be lost to the listener, both casual and experienced. Those talks often underline the shared concerns of generations across time and space, reminding us that we’re not alone and that, as the Kohelet puts it, “there is nothing new under the sun.”

A Call for the Arts to Comfort, Inspire, Instruct, and Help Lead

That said, there’s always a danger, in discussions like these, to slip into a utopian mindset. If the right music is played, the correct messages conveyed, then the audience will respond and, à la The Cradle Will Rock, rise up as one at the end. The crowd in the theater flows into the streets, the masses see the light, and, sure as day follows night, the proper kind of change ensues.

The reality is usually far grimmer.

Bildung didn’t save Europe’s Jews or spare the globe the ravages of multiple world wars. Weill and Brecht were part of an illustrious exodus of artists who fled post-1933 Germany. Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and countless others were forced to divine the impenetrable labyrinth of Soviet artistic policy at their peril. Even the dream of art spurring the mind into action has limited provenance: just ask the culturally literate Soviet audiences who heard Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony under Stalin, Khrushchev, and Brezhnev.

Besides, it’s not as though one side of the political divide has a monopoly on making artistic statements. Wagner and Beethoven were made to speak for Hitler. John Powell, for one, freely channeled his racism into his music. Today, any number of artists vigorously embrace anti-equality, -immigrant, and -leftist viewpoints. What’s more, the foes of reason, decency, and good-faith arguments are more than adept at manipulating outrage. Where does that leave us?

Andris Nelsons conducts the BSO in a performance of Wake Up! Concerto for Orchestra by Carlos Simon. Photo: Michael J. Lutch

Hopefully more clear-eyed as to the challenges ahead than not. Music and art alone won’t save us. They’re not replacements for actions that people must take themselves. But they can help us along.

Seventy-one days after Furtwängler conducted Brahms in the Musikverein, the Nazis, in a final spasm of violence, put to the sword the last members of the resistance in their custody, among them the dissident theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer. As related by his biographer Charles Marsh, in his will Bonhoeffer bequeathed a clavichord to his 15-year-old godson, Christoph, should “he take pleasure in it.” The same day Bonhoeffer met his end, Christoph’s father, the jurist Hans von Dohnányi, was executed in Sachsenhausen.

What happened to the instrument is lost to history, but Christoph von Dohnányi became one of the postwar era’s great conductors. In time, he followed in Furtwängler’s footsteps, leading the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna State Opera as well as the Berlin Philharmonic. Keeping with the family tradition, his life and career interacted energetically with the wider world: “I believe it is essential to be interested in what is going on around us,” he told a journalist in 2002. As such, von Dohnányi’s example forms an interesting counterpoint to Furtwängler’s — after all, his conducting continued many of the same musical traditions the older maestro revered.

That said, Furtwängler makes for a complicated scapegoat. He had legitimate reasons to remain in Germany, though, once he made his choice, he was only faced with bad options. In that, he’s a more sympathetic figure than not. Indeed, as I wrote a couple of years ago, there’s more than a little bit of Furtwängler in all of us, “quick to equivocate, justify, and play things safe — and, hopefully, to our advantage — all the while hoping for the best. Such is human nature. Courage is fleeting; moral courage, especially so.”

Knowing this, let us contend with the future bravely. However late the hour and however long the road ahead, the cause of standing for justice, knowledge, and freedom isn’t yet doomed. Along the way, let the arts comfort, inspire, instruct, and help lead. That’s what they’re here for.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.