November Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Jazz

T.K. Blue may be a new name to you, but if you’ve listened to Abdullah Ibrahim records in the late ’70s or Randy Weston in the 1980s, you’ve heard his saxophone and unfussy arrangements.

T.K. Blue may be a new name to you, but if you’ve listened to Abdullah Ibrahim records in the late ’70s or Randy Weston in the 1980s, you’ve heard his saxophone and unfussy arrangements.

T.K. Blue’s Planet Bluu is a multigenerational affair. Veteran trombonist Steve Turre is here (underused), and so is his son, drummer Orion Turre. Trumpeter Wallace Roney Jr., gifted with the impeccable jazz genes of Geri Allen and his father, makes a strong contribution.

The record showcases Blue’s skillful compositions and arrangements. Different styles are combined into seamless grooving wholes. “The Hue of Blue” juxtaposes angular bop with smooth samba. “Sky Bluu Part 2” kicks off an African rhythm with a subtle Latin feel, and I hear a bit of Cuban jump in the melody.

Standout arrangements include “Valley of the Bluu Rose,” which has horns trading fours at the start for a change. The melody is creative bop that inspires the soloists to stretch. “Chessman’s Delight” is an up-tempo, riff-based swinger with a Mingus-like feel. Orion Turre is fine on the drums, but you can tell he’s got a little ways to go.

Roney Jr. sounds more like Freddie Hubbard than his father’s mentor Miles Davis, spinning focused lines with confidence. Pianist Dave Kikoski can’t seem to settle down to one style — on some tracks he finds colorful chords to support the soloists, but on most other tracks he thunders in like McCoy Tyner and dominates where he should probably lay back.

Blue himself has a tart, unpolished tone and a straightforward melodic concept. He’s also a virtuoso on kalimba, a simple instrument that adds a surprising amount of sonic and rhythmic diversity in his hands.

Planet Bluu is a fun and engaging listen as the seasoned pros pass the tradition to the next generation.

— Allen Michie

Classical Music

Kenneth Hamilton is a virtuosic pianist with a healthy curiosity. I have previously hailed recordings of him playing Chopin, Liszt (including the B-Minor Sonata), more Liszt (including fantasies on themes from operas of the day), and “Romantic Piano Encores.” Now he brings us works from Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Percy Grainger, and others, all based on musical styles of the Baroque era, as well as arrangements of, and fantasies based on, specific works of Handel and, in one case, Gluck. (Click to try tracks or to purchase.) The arrangements and fantasies come from three of the greatest pianists in history: Liszt, Charles-Valentin Alkan, and — much more recent — Wilhelm Kempff (1895-1991).

Hamilton’s nimble fingerings and subtle pedaling work wonders in pieces that have been often recorded, including Mozart’s “A Little Gigue,” Beethoven’s 32 Variations in C Minor, and Brahms’s massive Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Handel.

Equally involving are pieces much more rarely heard, such as Alkan’s “bracingly vigorous” (as Hamilton nicely puts it) version of a chorus from Handel’s oratorio Samson and Liszt’s complex, 11-minute-long fantasy on two dances from Handel’s early opera Almira. (Handel later adapted the Almira sarabande for what would become one of his most famous arias: “Lascia ch’io pianga,” in Rinaldo.)

I was particularly delighted to hear Brahms’s arrangement of a Gavotte from Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide. I first encountered it in Paris, decades ago, as an encore played by an aging but still very capable Kempff. Brahms’s arrangement was praised by Wagner, and, in Hamilton’s hands, two eras a century apart merge into a timeless new unity (or three eras, counting ours!).

Hamilton’s booklet essay is, as usual with his CDs, full of humor, information, and fresh insights. All in all, I felt that I had just attended a gloriously varied recital, hosted by the performer himself.

— Ralph P. Locke

Bach aside, personal religious devotion doesn’t always translate into great sacred music. To wit: the Requiems of Berlioz and Verdi were written by, respectively, an atheist and a skeptic. Similarly, two of the most inviting settings of the Mass Ordinary came from the pens of those worldly Italians Gioacchino Rossini and Giacomo Puccini.

Bach aside, personal religious devotion doesn’t always translate into great sacred music. To wit: the Requiems of Berlioz and Verdi were written by, respectively, an atheist and a skeptic. Similarly, two of the most inviting settings of the Mass Ordinary came from the pens of those worldly Italians Gioacchino Rossini and Giacomo Puccini.

While the former’s Petite Messe Solennelle runs about as long as Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, the latter’s early Messa di Gloria is the picture of concision, clocking in at a crisp 45 minutes or so. Though not the most profound setting of these texts, Puccini’s effort doesn’t stint on charm or solid melodic ideas.

Alas, those qualities are a bit muddled in the work’s latest recording (BR Klassik) from the Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks and the Münchner Rundfunkorchester led by Ivan Repušić. That’s not to say the performance is technically deficient. All hands sing and play strongly. Theirs is a perfectly respectable, solid Messa. It just doesn’t regularly rise beyond that.

In general, tempos are a shade too spacious and phrasings feel deliberate. The noble “Qui tollis,” for instance, is noble and stately — but then slows down as it goes on. The chorus’s interjections in the “Agnus Dei” feel mannered.

Unfortunately, the spirit of restraint hovers over everything else, from the “Kyrie’s” warm blend to the ringing a cappella spots in the “Et incarnatus est,” and the welcome solo contributions of tenor Tomislav Mužek and baritone George Petean.

Nor does the recording’s engineering help: choral and orchestral textures often sound unnaturally flattened and indistinct. Better to stick with either Pappano (on Warner) or Morandi (on Naxos) in this piece.

Happily, Repušić and his orchestra are far more persuasive in the filler. The Preludio sinfonico is warmly Italianate and flowing while the short I Crisantemi sings hauntingly.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

More than three decades after he died, Leonard Bernstein is back — in recorded form, at least — with a “new” recording from the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra taped all the way back in 1983. Lest one wonder if the delay owes anything to the quality of the performance, rest assured: it doesn’t.

More than three decades after he died, Leonard Bernstein is back — in recorded form, at least — with a “new” recording from the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra taped all the way back in 1983. Lest one wonder if the delay owes anything to the quality of the performance, rest assured: it doesn’t.

In fact, the album (from BR Klassik), which pairs Robert Schumann’s Symphony No. 2 with Bernstein’s own Divertimento, showcases both Bernstein and his Bavarian forces at their collective best.

The Schumann was one of the conductor’s party pieces and the current performance predates Bernstein’s account for his cycle with the Vienna Philharmonic by about two years. This Second falls somewhere in between that magisterial Vienna one and his kinetic New York Philharmonic taping from the ’60s: flowing, well-directed, and, in the gorgeous Adagio, richly colored.

For filler, the charming Divertimento has rarely sounded better on disc, at least under Bernstein’s direction. The Bavarian orchestra has the full measure of its playful style — not to mention the exposed, sometimes treacherous instrumental writing — well in hand.

The performances, both recorded live in Munich’s Herkulessaal, include minimal extraneous noise and serve as a welcome reminder of the humanity and exuberance that Bernstein, even in his tortured last decade, still brought to his appearances.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

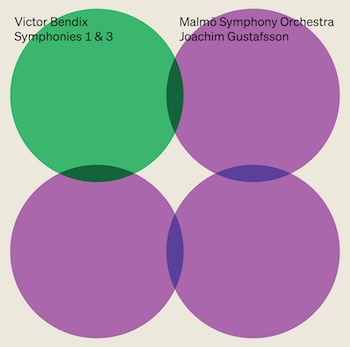

German composers seem to dominate the symphony, but some of the most interesting entries in the genre come from the country just north: Denmark. Between Niels Gade, Carl Nielsen, and Rued Langaard, the Danes, for more than a century, punched above their weight. Now add Victor Bendix to the list.

German composers seem to dominate the symphony, but some of the most interesting entries in the genre come from the country just north: Denmark. Between Niels Gade, Carl Nielsen, and Rued Langaard, the Danes, for more than a century, punched above their weight. Now add Victor Bendix to the list.

An older contemporary of Nielsen’s (the younger composer dedicated his Symphonic Suite to him), Bendix only wrote four symphonies, his career marked by various professional disappointments, an evidently touchy personality, and a scandalous personal life.

Nevertheless, the Malmö Symphony Orchestra’s recent release of Bendix’s Symphonies Nos. 1 and 3 (Ondine) reveals a composer whose idiosyncratic approach to structure, command of instrumentation, and melodic gifts are fresh and compelling.

The First Symphony, subtitled “Ascension,” offers a Langaard-esque program involving scaling a mountain (plus all the attendant metaphorical spiritual associations). If, on paper, its four movements — Overture, Nocturne, Solemn March, and Finale — imply a suite, the music’s dimensions and its thematic relationships are clearly symphonic.

In the Third, the writing exudes melancholy and autumnal grandeur. The scoring in its first movement periodically recalls Elgarian delicacy. The central Scherzo sounds rather like light-footed Bruckner. Mahler-worthy textures proliferate in the finale; so, too, seeming anticipations of Thomas Adès’s manipulations of rhythm and sonority.

The playing of the Malmö ensemble, which is led by Joachim Gustafsson, is, throughout, superb. Theirs are shapely, impassioned readings that are also beautifully recorded. Equally impressive are Jens Cornelius’s insightful liner notes. All in all, the album’s a terrific discovery and a welcome addition to the discography of the Scandinavian symphonic tradition.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Books

Betsy Lerner’s Shred Sisters is a novel (Grove Atlantic) about a woman’s challenging experience of coming-of-age with an older mentally ill sister. This is a sibling whose outsized presence not only disrupts the relationships within a family, but undercuts her younger sister’s potential for intimacy. The two sisters, Olivia (Ollie for short) and Amy Shred, could not be more different. Ollie exhibits bipolar tendencies and embodies chaos; Amy clings to order. Lerner skillfully dramatizes the pair’s yin/yang; here the contraries chow down at a salad bar: “When it was my turn, I’d make a show of using the correct tongs to take my fair share from each container, while Ollie would plunge the same tongs into every container, heaping coleslaw on her plate, then olives, and a stockpile of croutons on top. It wasn’t a crime, but it stood for everything I couldn’t stand about her.”

Lerner explores, by way of a great deal of wit and insight, the ways mental illness can undercut the health of a family. In the case of the narrator, the damage endures long after childhood. Growing up with, compensating for, a mentally ill sister shapes Amy’s sensibility in fascinatingly harmful ways. She is afflicted with an obsessive need to measure and assess the risk of every part of her life. Amy is determined to reduce chaos and ambiguity by hewing to the rules, mastering the games of probability. A veteran literary agent and editor who has written three previous books of nonfiction, Lerner is good at conveying sisterly disaffection; she is less successful at evoking the love between the siblings. Still, her debut novel offers a concise, tragicomic vision of family dysfunction.

— Joy Loftus

Megan S. Raschig, a professor of anthropology at California State University in Sacramento, spent considerable time studying women in the Salinas area. She was doing anthropological research, but she was also intimately involved as a participant with the efforts of the women to fight injustice and racism in their community. Healing Movements: Chicanx-Indigenous Activism and Criminal Justice in California (New York University Press) contains the fruits of her activism and research.

Megan S. Raschig, a professor of anthropology at California State University in Sacramento, spent considerable time studying women in the Salinas area. She was doing anthropological research, but she was also intimately involved as a participant with the efforts of the women to fight injustice and racism in their community. Healing Movements: Chicanx-Indigenous Activism and Criminal Justice in California (New York University Press) contains the fruits of her activism and research.

Much of what Raschig discovered is encouraging. The “Chicanx-Indigenous Activism” she references includes effective protests against police violence, successful efforts to prevent plans to enlarge the facility for incarcerating young men in the community (despite dropping crime levels), and various healing practices, some of them involving Indigenous rituals and languages.

Law enforcement views gang membership as a contributor to criminal activity. Raschig argues that many of the women with whom she became acquainted had formed lasting friendships and support groups through associations that began with gang membership. She insists on the importance of nurturing mutual support, no matter how that support begins.

Healing Movements is at its best when it dramatizes how traumas have united a tough-minded community of women. Their neighborhoods have been over-policed; they have seen their sons demonized and incarcerated; they have witnessed the murders by police of men and women who should have been receiving treatment for serious mental health issues.

Raschig is a social scientist, so Healing Movement‘s language may put off lay readers. For example, she notes a “susceptibility to colonial and carceral logics and structures: the disposability at the heart of radicalized criminalization, rooted in settler colonial dispossession.” Jargon like this is confusing, but along with that the book contains powerful stories of strong women successfully defending themselves and their community from the challenges oppression poses to America’s minorities.

— Bill Littlefield

Nicholas Fox Weber’s exhaustive and exhausting new biography, Mondrian: His Life, His Art, His Quest for the Absolute (Knopf), presents to readers, in great detail, the philosophies, beliefs, and eccentricities that preoccupied the mind and influenced the paintings of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century: Piet Mondrian.

Born in the Netherlands in 1872, Mondrian grew up with and was trained by his stern Calvinist father, who saw visual art as a conduit to the realm of God. His teachings inspired young Mondrian to draw and paint, talents he put to use soon after he received his certificate to formally teach, where he located as an independent, working artist in Amsterdam and Paris. As he grew older, Mondrian’s style, which was more traditional early on in his career, matured due to his fascination with Theosophy, Impressionism, and Cubism. These enthusiasms led to his foray into painting geometric shapes (primarily squares), impeccably produced straight lines, and a color palette. Some, like Weber, see these pictures as vibrant and alive, while others see them as diametrical, dull, and lifeless.

Weber’s interpretations of Mondrian’s paintings are persuasive; his compelling passion for the artist’s work from the biographer’s childhood. He writes about Mondrian as if he knew him personally, making sure he gets everything down, sometimes spending a bit too much time detailing the inconsequential. That urge for completeness makes the text a daunting as well as an impressive reading experience. It is as multivalent as Mondrian himself, who was awkward with women, notoriously introverted and secretive, sickly, an ardent antisemite, and an incessant but unaccomplished dancer. Over time, the artist became more at ease with himself and his surroundings. Weber’s biography will reward those who want to explore all the different sides of the life and work of a most complicated Modernist master.

— Douglas C. MacLeod

Written between 2015 and 2016, with 53 color images of well-known old masters and contemporary art as well as some of the Bergers’ own drawings and watercolors, Over to You: Letters Between a Father & Son (Pantheon) is a slender volume in which the respected and unapologetically Marxist art critic John Berger (1926-2017) — the author of eight novels (including the Booker Prize winning G), four plays, two books of poetry, and 52 books of nonfiction, including Ways of Seeing — exchanges views on life and art with his son Yves (b. 1976), a writer, artist, and poet.

Written between 2015 and 2016, with 53 color images of well-known old masters and contemporary art as well as some of the Bergers’ own drawings and watercolors, Over to You: Letters Between a Father & Son (Pantheon) is a slender volume in which the respected and unapologetically Marxist art critic John Berger (1926-2017) — the author of eight novels (including the Booker Prize winning G), four plays, two books of poetry, and 52 books of nonfiction, including Ways of Seeing — exchanges views on life and art with his son Yves (b. 1976), a writer, artist, and poet.

During the genial conversation the pair posit observations on pictures by a range of artists, Van Gogh, Chaïm Soutine, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Max Beckmann, Albrecht Dürer, and Helene Schjerfbeck among them. Gnomic statements abound from both writers, including this particularly intriguing one from John: “In their later work, Giacometti will become, within the European tradition, a kind of calligrapher. And Helene Schjerfbeck a kind of keener.” The back-and-forth resonates with mutual affection between parent and child as the two mull over unsolvable issues, such as John’s claim that painting is “the recuperation of the invisible.”

One wishes Over to You’ s focus were wider. For example, John Berger, at age 88, had just published his collected poems the year before. And there isn’t much on the relationship between art and politics, about how, for the elder Berger, aesthetics can generate a collective power. Though Yves might be referring to the latter when he uses the word “comrades.”

I’ve always heard you address the Old Masters or writers or thinkers, those you admire and feel gratitude toward, as if they were comrades, standing right there, by our sides. Their physical absence — most of them long dead — doesn’t make the slightest difference. What has been lost is insignificant compared with their ongoing presence. A presence established not only by their works they left but also by the intensity of their impulse toward what they sought.

John Berger did not write a memoir, so Over to You is valuable if only because it gives us a sense of what it was like to have a call and response with his “ongoing presence.”

— Bill Marx

Afro Pop

The cover art for Citizen Deep’s Arcade Trilogy.

The South African genre of amapiano aims to be an absorbing universe. Its songs commonly run seven minutes and albums can go on for several hours. Over the three parts of his Arcade series (Piano Hub Records), Citizen Deep confirms that he is a producer with great taste when it comes to choosing featured vocalists (15 alone in the first half of his latest album, Arcade Trilogy) and an infectious love of variety. The second disc of Arcade Trilogy has been mixed in a way that blends the songs together.

Amapiano borrows from American R&B and house music, synthesizing them with South African rhythms and instruments, such as the log drum and kalimba. Citizen Deep’s songwriting avoids the genre’s “vibes over melody” tendencies, even though his loops of carefully assembled percussion take the lead. (The track “Phula” treats vocal samples as if they were drums.) Citizen Deep successfully creates a sophisticated interplay between singing and drumming; other instruments are brought in for flavoring. “You” contrasts a rapid-fire beat with Thandazo’s slower vocals. “Mia’s Prayer” evokes the eclectic British group SAULT’s forays into gospel.

Without wallowing in misery, Arcade Trilogy travels into some forlorn, anxious places. With its jittery pulse, “Let You Go” ponders “why could you let me go?” “Bafana Base Zola” is sung in Swahili but, even without understanding the lyrics, its mood of sadness is striking.

Arcade Trilogy hovers in the vicinity of neo-soul and quiet storm R&B, but its skillful use of percussion and keyboards introduce degrees of stress. On the one hand, Citizen Deep’s version of dance music never escapes from trouble. Even the warmth of his slower songs heightens their sadness. Yet the album remains sympathetic to its sufferers throughout, signified by Kususa singing “let Mama hold you now” tenderly. Arcade Trilogy is melancholic, but its gloom takes place in full sunshine.

— Steve Erickson

Visual Art

The Unseen by Adrian Wall, 2024, granite. Photo: Andres institute of Art

Each year since 1998, except for two Covid-19 years, a sculpture mountain in Southern New Hampshire, once a ski resort and earlier a granite quarry, has celebrated art and nature. This year, on October 8, the Andres Institute of Art held the closing ceremony for the 24th International Bridges & Connections Sculpture Symposium.

The 24th Annual Symposium continued the tradition of bringing global artists together to collaborate, learn about, and create public art in a natural setting. By the end of each Symposium, new works are added to Big Bear Mountain. Since the beginning of the Symposia, 106 sculptures have been completed and placed by more than 80 artists. Over a dozen others were created by master sculptor and Institute director John Weidman.

During their three-week residencies this year each artist created distinctive and eloquent sculptural statements. Canada’s Morton Burke, of Alberta, added to his creative tool kit, learning to skillfully weld so he could complete a large steel sculpture, Into the Wind. Inspired by the winds that swirl at the top of New Hampshire’s Mt. Washington, Burke used recycled metal pieces from the Andres’s old quarry to create a striking artwork.

New Mexico’s Adrian Wall sculpted The Unseen, a piece that spoke to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women that span from Central America to Alaska. Almost classical in form, the head of an Indigenous woman represents how Native people have been marginalized. Wall’s goal was to infuse beauty into what is a painful conversation. And his figurative sculpture does that.

Maine’s Jim Larson contributed Remember These Raw Remnants. Made from granite, this monumental abstract piece reflects the perspective of 18th-century quarry workers. Imagination and historical reality are effectively juxtaposed in this monumental sculptural form.

Located about 90 minutes from Boston, along the New Hampshire/Massachusetts border in Brookline, NH, the Andres Institute of Art boasts 12 miles of trails, enhanced by public art, on its 140-acre grounds. Admission is free and open to the public year-round from dawn to dusk. Donations are welcomed.

— Mark Favermann

Film

Pop star Robbie Williams takes the form of a CGI chimpanzee in Better Man.

As an American, I am vaguely familiar with British pop star Robbie Williams. I remember his music video “Rock DJ,” where he gradually stripped his clothes off and then his skin, and the song “Angels.” Still, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from the biopic Better Man, especially when I learned that Williams takes the form of a CGI chimpanzee.

Jonno Davies plays Williams (via motion capture) while Williams voices himself. At no point does the film explain why Williams is a chimp. (There are no other chimps in the movie.) Everyone else is a human. At first, watching a monkey play soccer with the local lads, I burst out laughing. The truth is, I never took this conceit (metaphor?) seriously. I found myself guffawing at dramatic moments, such as when Robbie the chimp was doing cocaine before going on stage.

Directed by Michael Gracey, who helmed The Greatest Showman, Better Man plays out like a typical musician’s biopic, aside from the animal imposture. All the familiar beats are here: Williams knows he’s meant for greatness, he’s screwed over by a music producer, he reaches stardom, starts his downward slide because of drugs, etc. The departures from convention are: a) this all happens to a CGI chimp and b) Williams’s trials and tribulations play out like a prolonged Pepsi commercial because of Gracey’s canned-to-the-max direction. There are some impressive moments, particularly an extensive dance sequence across the streets of London. But they are matched by some absurd headshakers, such as the scene where Williams battles it out with his “inner” demons — who are other chimps.

You have to hand it to Better Man. It is unlike any other biopic I’ve ever seen. If Hollywood insists on giving us more examples of the genre that no one asked for or cares about, then let them serve up more like this: completely off-the-wall. Enough of the mundane remakes and sequels: give us wild biopics where the protagonist is played by an animal or an insect.

— Sarah Osman