Author Interview: A Mindset at the Crossroads of the Teutonic and the Semitic — A Conversation with Writer-Translator Peter Wortsman

By Bill Marx

A translator must meet a compelling need — to reinvent Franz Kafka’s voice in an English that resounds in the present moment.

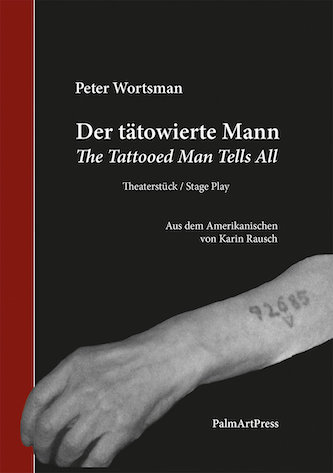

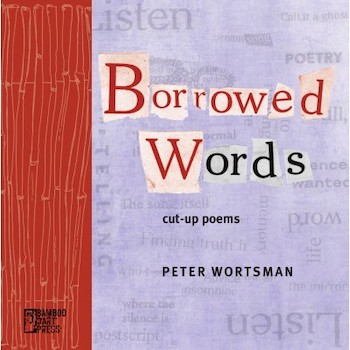

It is time to celebrate a banner creative period for a writer-translator I admire, Peter Wortsman. Between 2023 and 2024, he will have published five books: a book of poetry, Borrowed Words; a bilingual (German/English) edition of his stage play Der tätowierte Mann/ The Tattooed Man Tells All; two translations from the German, The Golden Pot, And Other Tales of the Uncanny and I Just Let Life Rain Down on Me, Selected Letters and Reflections of Rahel Levin Varnhagen; and an original take on a medieval favorite, Odd Birds & Fat Cats, An Urban Bestiary, a collaboration with his daughter, Aurélie Bernard Wortsman (his texts, her illustrations), forthcoming in 2024 from Turtle Point Press.

It is time to celebrate a banner creative period for a writer-translator I admire, Peter Wortsman. Between 2023 and 2024, he will have published five books: a book of poetry, Borrowed Words; a bilingual (German/English) edition of his stage play Der tätowierte Mann/ The Tattooed Man Tells All; two translations from the German, The Golden Pot, And Other Tales of the Uncanny and I Just Let Life Rain Down on Me, Selected Letters and Reflections of Rahel Levin Varnhagen; and an original take on a medieval favorite, Odd Birds & Fat Cats, An Urban Bestiary, a collaboration with his daughter, Aurélie Bernard Wortsman (his texts, her illustrations), forthcoming in 2024 from Turtle Point Press.

Sadly, challenging circumstances make this a particularly good time to get the word out about Wortsman’s literary accomplishments. Diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and more recently with a debilitating neuropathy in his hands and feet that make it difficult to write and walk, his creative output has, if anything, increased. Wortsman is currently at work on a new book of poetry, The Laboratory of Time, a dystopian novel, Pleasant Dreams, and a travel memoir titled Reflections of a Faltering Traveler in the Land of the Rising Sun, in which he addresses his illness and encourages others suffering from chronic illness not to let it crimp their style.

I interviewed Wortsman in 2016 about translating Franz Kafka, but this is an anniversary year, so I had to ask him about Kafka again, well as get his thoughts about some of his own work.

The Arts Fuse: June 2024 marked the 100th anniversary of the death of Franz Kafka. Isaac Bashevis Singer once opined that one Franz Kafka is enough — better to have a thousand Tolstoys. Do you agree?

Peter Wortsman: I’m not quite sure what Singer meant by that assessment. Kafka is unquestionably one of a kind, a modern-day scribe able to take dictation directly from the unconscious, and to present the ineffable in the crisp, clear language of a legal brief. His mindset sits at the crossroads of the Semitic and the Teutonic. A master of German syntax, his writing style harkens back to that of Heinrich von Kleist. But his penchant for parables is as much rooted in Old Testament narratives like “The Book of Jonah” and “The Book of Job,” as in the Märchen of the Brothers Grimm and the uncanny tales of E.T A. Hoffmann. Kafka had his predecessors and literary heirs. I tried to reconstitute that tradition in my anthology, Tales of the German Imagination, from the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann (Penguin Classics, 2012).

Writer-translator Peter Wortsman. Photo: Jean-Luc Fievet

AF You have translated a selection of Kafka’s work, as well as prose by writers he admired, Heinrich Von Kleist and Robert Musil. What are the challenges of translating Kafka into English in the new millennium?

Wortsman: In 1984, the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, presented a visionary exhibition titled “Le Siécle de Kafka” (Kafka’s Century), with an accompanying catalogue of the same title, juxtaposing enigmatic 20th-century artworks by Arp, Giacometti, Michaux, Nevelson, Richter, et al with quotes by contemporary authors of note, texts either inspired by Kafka, or of a kindred nightmarish vein, along with a copy of Michael, A German Destiny in Diary Form, a semi-autobiographical novel by Dr. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s master propagandist. “In the Penal Colony,” Kafka’s prophetic narrative set in an imagined prison colony with a refined tool of torment, might well be read in hindsight as an imagined dialogue with Dr. Goebbels, and a blueprint of dire things to come. In this deeply disturbing story, a mechanical device conceived to literally etch a criminal’s crime and sentence in his body and his mind is proudly presented by the officer in charge of its operation, demonstrating its efficacy on a docile convict, for the benefit of a visiting traveler from afar. But the demonstration does not go as planned. The mechanism malfunctions, and the officer is obliged to trade places with the convict and try the sentence on himself, a bit like the befuddled witch in “Hansel and Gretel” compelled to climb into the oven in which she planned to bake the boy.

Interpreting Kafka’s nightmarish narratives today, the reader must, necessarily, take recent history into account, notably the horrors of the Holocaust. Still, the only essential difference between translating Kafka into English between 1930 and 1949, when Edwin and Muir took a first stab at it, enshrining his prose in the King’s English, and translating it now in 2024, a century after his passing, is the need to reinvent Kafka’s voice in an English that resounds in the present moment. As novelist Cynthia Ozick once put it in a New Yorker piece titled “The Impossibility of Translating Franz Kafka”: “After all, it is Kafka’s voice we want to hear, not the 1930s prose effects of a pair of zealous Britishers.”

The near canonical status of Kafka’s enigmatic prose presents another problem for the translator. Obliged to ignore the author’s notoriety, the translator must treat each word the same as he would the words of anyone else.

AF Are all the translations of Kafka that are currently available necessary? And what distinguishes your translations from others?

Wortsman: Permit me, in response, to cite my own musings published in the afterword to my take, Konundrum, Selected Prose of Franz Kafka (Archipelago Books, 2016): “English-language readers have the Orkney Island-born poet, novelist and translator, Edwin Muir, and his wife Willa (née Anderson), co-recipients of the Johann Heinrich Voss Translation Award, to thank for first transmitting the mysteries of Kafka into our hybrid Anglo-Saxon-Norman tongue. Other respected English translators who have each given it a go include: Anthea Bell, Ross Benjamin, Susan Bernofsky, Shelley Frisch, Mark Harman, Breon Mitchell, Joachim Neugroschel, Idris Parry, and Malcolm Pasley.

What then impels yet another Übersetzer to tackle Kafka? I once heard the translator likened to a musician or an actor, and I think there is some truth to the comparison. Both apply artistry, insight, cunning and craft, working from a track, a musical score, a script of dialogue, or a string of sentences, jotted down by a sentient being in another time and place. Like the musician, the translator attempts to listen in, as it were, on the whisper and howl of the original, to capture an echo of the original, and by reformulating rhythm and meaning, to tap the heartbeat and reanimate the breath enveloped by the silence of eternity. The music of Beethoven and Bach has been interpreted time and again, as have the plays of Calderon, Shakespeare, and Racine, which does not keep new conductors and instrumentalists, directors, actors and translators from taking a crack at it.

It would be arrogant of me to assert the superiority of my English take on Kafka, but I believe that in my translation, I have honed closely, breath by breath, syllable by syllable, to the psychic track he lay down. I take some pride in the fact that when the Museum Villa Stuck, in Munich, sought to assemble a celebratory volume to mark the centennial of Kafka’s death, they decided to accompany the original text of Kafka’s nightmarish narrative, “In der Strafkolonie,” with, among other texts and commentaries, a graphic novel inspired by it written by David Zane Mairowitz and illustrated by Robert Crumb, and with multiple other English translations to choose from, they picked mine to close with, literally the last words in the book.

AF: You recently published I Just Let Life Rain Down on Me: Selected Letters and Reflections of Rahel Levin Varnhagen, the first English translations of Rahel’s letters. Why put together this volume of prose by the illustrious late-18th century/early 19th century German Jewish literary-salon hostess now?

Wortsman: As I wrote in my introduction: “There are some writers you read and revere from a distance, awestruck, but never quite warming up to their voice, and others with whom you feel an immediate affinity, as with a newfound friend. Such was and is the case of my rapport with Rahel Levin Varnhagen. The epistolary form is particularly conducive to such a sense of proximity.

From the start, I conceived of this book, I Just Let Life Rain Down on Me, as an excerpt from a virtual conversation. It is high time the world took note of the writing of this extraordinary woman of letters. In the German-speaking world, Rahel Varnhagen von Ense, Née Levin, the illustrious German-Jewish literary salon hostess (1771-1833), is likewise known for the eloquence of her letters, over 10,000 of which she penned in the course or her life to more than 300 recipients, including princes, philosophers, poets, family members, and the family cook; some 6,000 of her letters are still extant today. Written with a wink at posterity, clearly conceived as compositions worth preserving, collected and published after her passing by her husband, Karl August Varnhagen von Ense (1785-1858), they constitute a singular contribution to German literature.

AF: In your introduction to I Just Let Life Rain Down on Me, your selection and translation of letters and reflections by Rahel Levin Varnhagen (Kolkata: 2024, Seagull Books) you mention that Rahel’s letters bring the letters of Kafka to mind — both reflect “a uniquely Jewish mix of intellectual acuity and profound emotional insecurity.” In what ways does Rahel’s gender shape her combination of smarts and vulnerability.

Wortsman: Permit me to respond to your question with an excerpt from my translation of two of her letters, one to a friend, David Veit, and the other to her younger sister Rose:

“If my mother had been kind-hearted and hard enough, and she could only have anticipated what I would become, she would have let me suffocate in the dust at my first cry. [. . . ] I have such a vivid imagination; it sometimes seems to me as if an extraterrestrial being incised these words with a dagger in my heart upon my entry into this world: ‘Yes, you may be endowed with a special sensibility, you may see the world as few others see it, be great and noble, nor can I deny you a thoughtful nature. But we forgot one thing: You are doomed to be a Jewess!’ And thus, my entire life is a bleeding to death! [. . . ] I can trace every mishap, every calamity in life, every chagrin back to that!”

Or as Rahel phrased it in a letter to her younger sister Rose (1781–1853): “I am a Jewess, not beautiful, ignorant, without grace, without talents and instruction. Oh, my sister, it’s all over; it’s finished before the real finale. I could not have done anything differently. [ . . . ] Meanwhile, we grow old and life falls away like old dreams.”

AF: In 2018, I reviewed a production of your play The Tattooed Man Tells All, which details the experiences of Holocaust survivors, based on interviews with the victims. How does your script fit in with other efforts to dramatize the catastrophe?

AF: In 2018, I reviewed a production of your play The Tattooed Man Tells All, which details the experiences of Holocaust survivors, based on interviews with the victims. How does your script fit in with other efforts to dramatize the catastrophe?

Wortsman: Inspired by the interviews with aging survivors of the concentration camps I conducted in Vienna, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Israel, in 1975, on a fellowship from the Thomas J. Watson Foundation, my play The Tattooed Man Tells All was first produced in 2018 by the Silverthorne Theater Company, at the Hawks and Reed Performing Arts Center, in Greenfield, Mass. It was restaged, in a German translation by Karin Rausch, as Der tätowierte Mann, and ran, in the immediate wake of the Covid pandemic, for eight months, Oct. 2021 to May 2022, at the Deutsches Theater in Göttingen. The play was recently published in a bilingual (German/English) edition, Der tätowierte Man / The Tattooed Man Tells All, by Palm Art Press, in Berlin, in 2024.) The interviews on which the play is based comprise “The Peter Wortsman Collection of Oral History” at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

A one-man show, The Tattooed Man Tells All, is a spare, stark narrative that does exactly what its title suggests, it tells all.

As the protagonist, an aging survivor, puts it to an implied, albeit invisible, young interviewer, upon pulling his old zebra-striped camp uniform out of a closet and insisting that the interviewer, by implication, the audience try it on for size: “No, I insist! Now’s your chance! You wanted to know what it was really like! Try my skin on for size! That’s what you came for, isn’t it! A visceral thrill!… A harmless taste of Hell! Don’t worry, it won’t bite! It’s quite tame after so much time!”

Anyone seeking moral uplift or an emotional handle in the person of an Oskar Schindler or an Anne Frank will not find it here. In the words of the protagonist: “The others, the ‘heroes,’ they all glorify it, dress up themselves and that time…slap on a saintly halo, turn the stinking corpses into martyrs, perfumed, prettified by make-up artists for popular consumption. They slap on a moral at the end of the story. But the story isn’t fit for popular consumption. It has no saints, no martyrs, no moral, no end. You can’t have saints without miracles, and the only miracle was…well, making it from one moment to the next! […] You can’t make a morality play about a man who crapped in his pants. Or what do you think!? I’m no innocent little Anne Frank! I’ve got crap in my pants!”

AF: The Tattooed Man says, “We’re all damaged goods. The wheels still turn but you can hear the gears grinding.” You yourself are the New York-born son of Jewish refugees from Vienna; in much of what you translate the grinding wheels are Teutonic and Jewish. What do you find compelling about this conflict?

Wortsman: Permit me, yet again, to respond with a quote, this time from the afterword to my own bilingual, German/English, book of stories: Stimme und Atem, Out of Breath, Out of Time:

“Once upon a time there was a turbulent cultural melding, a marriage of two peoples that exploded again and again in outbursts of violence, nevertheless bearing rich fruits, a marriage that finally fell apart in a terrible divorce. This German-Jewish union, in the braided double helix of which the souls of the North Sea and the Mediterranean, of mountain climber and nomad met, a union dating back to Roman times, when the Jews first established small settlements along the Rhine, led to the heights and the depths of our modern era. One can only imagine a Marx, a Freud, a Kafka, a Wittgenstein, or an Einstein, among many other pathfinders of modernity, at the crossroads of strict German syntax, logic and idealism coupled with Talmudic justice and idealism. An elective affinity perhaps. I would rather speak of a productive symbiosis, like that of the bird that lives on the back of the bison and feeds on the insects in its fur before flying on. Only the fleas lose out in the deal.”

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Wonderful and brilliant interview –

Nice interview. I am currently finishing your The Golden Pot. I am a literature teacher in The Hood I often teach Andersen’s fairy tales to my students. We analyze paragraphs. Particularly descriptive ones.

I am very impressed with your keeping Hoffmann’s 19th century paragraphs intact while coming up with a vibrant language that both matches todays words with preserving the old depth. Quite a challenge you managed to meet.

I used to organize Holocaust survivors to speak to my students. Sam Sherron was a child in the camp with his father. He kept his tattoo and had us walk up to see it close to prove it was real. My kids from the Hood get it and understand. Your interviews and your play are more important than you probably realize.