May Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Books

In the remote mountain villages of Nepal, Seke is a language that is spoken by approximately six hundred people. Another hundred Seke speakers live in a single apartment building in Brooklyn, leading linguist/activist Ross Perlin to comment “this village has elevators.”

In the remote mountain villages of Nepal, Seke is a language that is spoken by approximately six hundred people. Another hundred Seke speakers live in a single apartment building in Brooklyn, leading linguist/activist Ross Perlin to comment “this village has elevators.”

Language City (Grove Atlantic, 432 pages) is an engrossing book about the race to save – or at least document – endangered minority languages that encode distinctive cultural worldviews in the time of homogenized global communications. Through the stories of six passionate native speakers of Seke (Tibeto-Burman), Wakhi (a Palmiri language from the region where Tajikistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China converge), Yiddish (the Eastern European Jewish language that has both a literary legacy and an emerging variant in New York’s Hasidic enclave), N’ko (a 27-letter written alphabet for a group of tonal Manding languages spoken by as many as 40 million people in West Africa, introduced as recently as 1949), Nahuatl (the Mexican language spoken by the ancient Toltecs and later Aztecs, Tlaxcalans, and others, resisting the onslaught of Spanish), and Lenape (the language of Manhattan’s original inhabitants), Perlin explains that New York has become not only a global microcosm but a natural experiment for cross-linguistic research.

Across a journey that is a little bit detective story, a little bit hero’s journey, Perlin is a humble narrator carried along by his seemingly quixotic mission. As co-director of the Endangered Language Alliance (ELA) which he describes as a cluttered office “where an eccentric extended family of linguists, language activists, polyglots, enthusiasts and ordinary New Yorkers tune in to the deeper frequencies of the surrounding city and by extension, the world,” he recognizes the hints languages leave behind in the names of places and relationships, and never disguises his dismay at the shadow of anti-immigration policies that has made multilingualism suspect rather than cherished. Twenty-first century New York may be the “consummate Babel” but it is one where unexpected proximity creates new opportunities for cooperation and engagement, at least until the tower falls down.

— Debra Cash

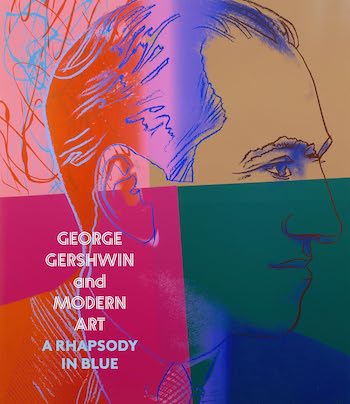

A gorgeous book just reached me that will be eagerly devoured by devotees of music and visual art alike. George Gershwin and Modern Art: A Rhapsody in Blue was researched and written by musicologist Olivia Mattis. An exhibition containing most of the artworks continues at the Baker Museum in Naples, Florida, through June 16; it has been reinforced with lectures and concerts.

A gorgeous book just reached me that will be eagerly devoured by devotees of music and visual art alike. George Gershwin and Modern Art: A Rhapsody in Blue was researched and written by musicologist Olivia Mattis. An exhibition containing most of the artworks continues at the Baker Museum in Naples, Florida, through June 16; it has been reinforced with lectures and concerts.

But the book stands majestically well on its own. It is available from the museum — telephone# 230-254-2646 — until July 28, and thereafter wherever books are sold.

Gershwin was a man of great personal style (as photos attest) and devoted to photography and to painting. Some paintings that he himself did are familiar, having been reproduced in books about him. But few lovers of music or of art realize how eagerly, and savvily, he collected the modern art of his day.

His multiple connections to visual art are now comprehensively established in Mattis’s book, which includes glowing, often full-page illustrations of first-rate works by (among others) George Bellows, John Carroll, Chagall, Dufy, Kandinsky, Klee, Kokoschka, Matisse, Modigliani, Noguchi, Picasso, Rouault, Shahn, Siqueiros, Utrillo, and Max Weber. Plus Gershwin-inspired works by Arthur Dove, Kara Walker, and (as in the eye-boggling cover image) Andy Warhol.

The book is further fleshed out with previously unknown letters between Gershwin and his art agent, Henry Botkin, and gives detailed provenance and current location for each artwork (as well as “exhibition history”).

It has been an astounding experience for me to read Gershwin’s words about certain paintings while drinking in the images of the painting(s) in question: “The two pictures that I have chosen [to purchase this time], … although modern in feeling, were a little more understandable than some of the others you sent, and I think, for a while[,] my tastes will run along these lines.” Modern-feeling yet understandable, just like Gershwin’s marvelous music!

— Ralph P. Locke

Eddie S. Glaude Jr.’s thoughtful meditation on James Baldwin, Begin Again, was so good I was eager to pick up We Are the Leaders We Have Been Looking For (Harvard University Press, 168 pages). Some time-machine adjustment is required: in a preface, Glaude informs the reader that these are the W.E.B. Du Bois lectures he delivered at Harvard University in 2011. Shift your mind back a decade: it will help you sympathize with the impulse driving this lucid exercise in social theory. Drawing on American philosophers, particularly Emerson and Dewey, and Black writers and thinkers, such as Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Toni Morrison, Glaude cuts against the deliriously heroic grain of the era. His argument: that overdependence on the power of charismatic leaders — figures of prophetic allure, such as Barack Obama — inevitably narrows the nature of political dissent in the Black community. Glaude points to an alternative tradition, represented by civil rights activist Ella Baker, whose strategy for ensuring the triumph of fairness and democracy “taps into the revolutionary possibility in self-cultivation on behalf of justice; that the effort to become the kinds of people democracy require — the kinds of people a racially just society demands — we transform our conditions of living.”

Glaude is no starry-eyed idealist, but he believes “we have to become better people if we are to change the world.” These words are well worth contemplating today, given the rise of brutal authoritarians around the world, including Trump-inspired fascism in this country. Articulate, passionate, and smart, We Are the Leaders We Have Been Looking For offers a rousing vision of the kind of political transformation that can only be generated from the bottom rather than the top. That said, we are in a period of pressing global emergencies: the climate crisis (it is time to call in Thoreau rather than Emerson), the looming threat of nuclear conflagration. Must we all become better people in order to make the decisions that are necessary to save the planet? Here’s a more mundane example: the United Auto Workers recently scored the largest union victory in decades in the South, successfully organizing at a Tennessee Volkswagen plant. Mutual interests brought the various worker factions together. Did everyone become a better person in order to make that happen? And if they didn’t, just how much does it matter?

— Bill Marx

Gospel Music

I was late to the party when it came to Sister Rosetta Tharpe. I’d known her name in passing, but hadn’t heard any recordings or seen a photo of the musician until she was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2018.

I was late to the party when it came to Sister Rosetta Tharpe. I’d known her name in passing, but hadn’t heard any recordings or seen a photo of the musician until she was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2018.

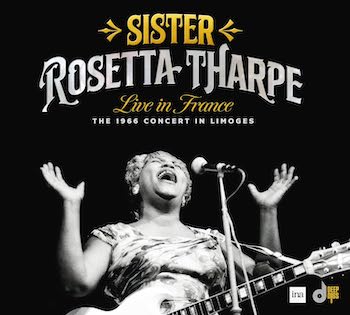

That’s when I visited YouTube, where I found a 1964 performance in which Tharpe, age 51, plugs in her white Les Paul Custom guitar, and tears into a rendition of the traditional gospel number “Didn’t It Rain.” I was gobsmacked.

Now, with the release of Live in France: The 1966 Concert in Limoges (Deep Digs Music Group), featuring 21 songs from a newly discovered show at the Grand Theater in France, I have 21 new reasons to celebrate. This is a solo gig — just Tharpe and her guitar, belting out Gospel tunes, R&B and a few originals.

With her voice in fine fettle and her fingers flying fluidly on the strings, she turns in a spirited performance, holding out long, sustained vocal phrases, adding some raspiness on the upper register notes, and mixing quiet passages with low growls and shouts.

There’s high intensity rockin’ on “Didn’t It Rain,” a sweet, mellow, and soulful take of “Mother’s Prayer,” splendid guitar work on “That’s All/Denomination Blues,” a funny “drunken” slurring of words on her own “Moonshine,” and excellent piano accompaniment – her own – on “Up Above My Head, I Hear Music in the Air.”

This is a gem of a live album, with superb sound quality that complements Tharpe’s joyous singing and playing. One of the chief reasons it all works so well: neither her energy nor the strength of her voice wanes, even though she keeps jumping forward to the next song with minimal time between them.

Live in France is not an album to sit back and relax to. You can’t help but tap your feet and shake your head. And it might be you that’s exhausted by the end.

– Ed Symkus

Folk Music

A Quebecois singer who has lived and worked in Canada, France, and the U.S., Myriam  Gendron’s artistic influences span North American folk traditions, the Leonard Cohen songs she sang as a busker in Paris, and Dorothy Parker’s poetry (set to music on her stark 2014 debut Not So Deep As a Well.) Gendron waited seven years before releasing her much longer follow-up, Ma délire – Songs of Love Lost and Found. “Dans la vieux pays,” an adaptation of a traditional song, accompanied by a feedback-laden guitar, suggests the album’s ambition. So did its video, in which Gendron performs against a movie screen while archival films of early 20th-century Canadian life are projected upon her.

Gendron’s artistic influences span North American folk traditions, the Leonard Cohen songs she sang as a busker in Paris, and Dorothy Parker’s poetry (set to music on her stark 2014 debut Not So Deep As a Well.) Gendron waited seven years before releasing her much longer follow-up, Ma délire – Songs of Love Lost and Found. “Dans la vieux pays,” an adaptation of a traditional song, accompanied by a feedback-laden guitar, suggests the album’s ambition. So did its video, in which Gendron performs against a movie screen while archival films of early 20th-century Canadian life are projected upon her.

Parker remains a touchstone on Mayday (as reflected in “Dorothy’s Blues”), as does Canadian folk music. But this album (on Thrill Jockey) feels more relaxed than Ma délire. The opening instrumental, “There Is No East Or West” sets the pace: Gendron picks a chiming acoustic guitar against a lower, bass-heavy tone. She places as much emphasis on mood as she does on melody. Even when playing solo, she juxtaposes trebly passages with sustained lower notes. Gendron’s music can often be stripped-down and straightforward: for example, “Quand j’étais jeune et belle.” Guitarists Marissa Anderson and Bill Nace and drummer Jim White join Gendron for more improvisatory contributions. During “Lully Lullay,” White’s fills on cymbals and tom-toms push forward into contrapuntal rhythms against the singer’s softer vocals and guitar. Gendron supplies a soft pulse with hand percussion on “La Luz.” “Terres brulees” samples nature sounds; even the dissonant violin is used gingerly. Ooh Amba’s saxophone break on “Berceuse” finally unleashes some noise into the picture, though it calms down by the song’s end. Though it doesn’t avoid drama, Mayday is a tonic for jangled nerves.

— Steve Erickson

Afropop

In Senegal and neighboring Gambia, as in much of West Africa, drums talk. They send messages through the air, from one drum ensemble to another, via percussive communiqués. The drum ensembles of the Wolof people of Senegal are led by the sabar player: the sabar is a tall, resonant drum that’s played with both hand and stick — it also gives this genre of music its name. The sabar player is a storyteller, or griot — in Wolof, he’s known as a géwël — and the ensemble’s leader. The accompaniment, on anywhere between six to twelve drums, is called a mbalax, and the phrases they create together create a sonic conversation, called a bàkk in Wolof.

In Senegal and neighboring Gambia, as in much of West Africa, drums talk. They send messages through the air, from one drum ensemble to another, via percussive communiqués. The drum ensembles of the Wolof people of Senegal are led by the sabar player: the sabar is a tall, resonant drum that’s played with both hand and stick — it also gives this genre of music its name. The sabar player is a storyteller, or griot — in Wolof, he’s known as a géwël — and the ensemble’s leader. The accompaniment, on anywhere between six to twelve drums, is called a mbalax, and the phrases they create together create a sonic conversation, called a bàkk in Wolof.

Aba Diop is a Senegalese sabar player who comes from a long line of griots; he’s also a sabar maker as well. Talk about knowing your instrument. On Diop’s new album with the Yermande Family, Revolution Sabar, he takes the traditional beat of the mbalax and turns it into pleasing Afropop. On the lute-like kora, there’s Noumoucounda Cissoko; on bass, Thierno Sarr; on tama, the “talking drum”, Samba Ndokh; on guitar, a young American, Jason Hosier; female vocals are provided by the exultant Zeyna Ngom, the lead vocals being sung by Diop himself, who also produced.

A mystical, romantic vibe colors the album’s eight tracks. Diop is a devotee of Baye Fall, a Senegalese branch of Sufism called Mouride. The opening number, “Selebayon”, is an invocation to the djinn, or spirits, at the crossroads of cultures. (The album is mostly sung in Wolof, with a soupçon of French.) “Serigne Cheikh Ndiguel Fall” follows, similar but more incantatory, as befits a song written for Diop’s spiritual guide. “Senegal” is a wistful tribute to his homeland and features some tasty kora. The closer, “Bellio Mbaye”, provides a satisfying polyrhythmic finale. This bàkk is beautiful stuff.

— Mark Hänser

Jazz

Saxophonist Scott Marshall has gigged with everyone from The Rascals to Marie Osmond. He currently teaches at the Oscar Peterson School of Music at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory. His latest self-released album is The Solitude Suite, which, like his previous six albums, is all-original compositions.

Saxophonist Scott Marshall has gigged with everyone from The Rascals to Marie Osmond. He currently teaches at the Oscar Peterson School of Music at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory. His latest self-released album is The Solitude Suite, which, like his previous six albums, is all-original compositions.

The CD was inspired by the “solitudes created by smartphones, social media algorithms, and divisive political discourse.” To reflect the loss of “middle ground” in society, Marshall leaves out any chordal instruments in his acoustic quartet.

Without piano or guitar, the sound is detached and floating. It compares to Ornette Coleman’s first pianoless quartet, but this isn’t free jazz. Marshall’s compositions stick to the changes, the arrangements are head-solo-head, and there’s no interplay among the sax and trumpet when they improvise. This makes you sometimes hear a piano or guitar in your imagination.

The “middle ground” role shifts not so much to Mike Downes’ walking bass, but to Terry Clarke’s drums. Rather than inversions and modulations, you get loud and soft, fast and slow, and different touches on the percussion as it responds to the soloists and steers them.

Kevin Turcotte’s trumpet is warm, stays in the middle register, and has a slightly blurry edge to it like Don Cherry’s. Marshall’s tenor is airy and fluid, in the Lester Young/Stan Getz tradition. They make an effective combination, especially when they play in straightforward harmonies.

“Conversations” is a good example of Marshall’s composing and playing talents. There’s tension-and-release as the melody’s sour harmonies unfold. The soprano solo makes effective use of the unusual intervals heard in the melody, taking them in new directions.

Turcotte has his own style. He especially caught my attention on the meditative “Reflection.” In a dissonant melody that recalls Yusef Lateef’s “Syn-Anthesia,” Turcotte plays long tones very quietly, without a mute, while still sounding expressively human. It’s a reminder that playing quietly is an advanced technical skill for trumpeters, too.

Marshall succeeds here with another document dedicated to his own highly personal musical vision.

— Allen Michie

Since the ’80s, pianist/composer/bandleader Fred Hersch has released dozens of recordings under his own leadership and dozens more as a sideman. I have many of them and I can’t remember a clunker in the bunch. Most are in the good to excellent range. This latest release sits in the good end of the spectrum.

A lot has been written about Hersch by me and other estimable Arts Fuse scribes. Through solo, duo, trio, and larger ensemble recordings, the now 68-year-old musician has placed his vision into various contexts — and the reviews are testaments to how he keeps it fresh.

For Silent, Listening, his first solo piano release on the ECM label, Hersch offers a variety of originals and standards that, once again, both subtly challenge and quietly engage the attentive listener. The proceedings may slip into idle a bit in a few spots but, overall, the benefits of this disc outweigh its shortcomings.

Hersch starts off the album by returning to a piece he recorded on his first album in 1985. His latest arrangement of the Ellington/Strayhorn tune “Star-Crossed Lovers” fits nicely into an ECM tradition of soloists working around the roots of a composition until a melody arises that quietly takes your breath away.

The original “Akrasia” features thoughtful improvisation: the pianist roves through his reserve of musical ideas to create a powerful dramatic ambiance. A little later on the disc, his take on Russ Freeman’s “The Wind” stirs up some darker emotional currents.

The Alec Wilder piece “The Winter of my Discontent” is another tune Hersch has returned to over the years. Like snow falling at dusk, the piece’s melody gently enfolds itself in shadows. Harmonies barely provide any comfort; the pianist seems to be reaching, perhaps haplessly, for an elusive memory.

One wishes that the fine reading of the classic “Softly, As in a Morning Sunrise” came after — rather than before — the wintry Wilder piece on the disc. But, in any case, Hersch is searching through the twilight, and listeners should be grateful they are being brought along on the melancholic quest.

— Steve Feeney

Steve Lacy could blow just a few notes on his soprano sax and rev up a sonic vehicle that would pick your ears up and lead them through a roiling vortex of melody and rhythm. His genius was often at its most powerful in collaboration with an optimal co-leader, like pianist Mal Waldron.

Steve Lacy could blow just a few notes on his soprano sax and rev up a sonic vehicle that would pick your ears up and lead them through a roiling vortex of melody and rhythm. His genius was often at its most powerful in collaboration with an optimal co-leader, like pianist Mal Waldron.

The Mighty Warriors, a previously unreleased and very well recorded live set made in Antwerp, Belgium in 1995 (on the occasion of Waldron’s 75th birthday) confirms that, for Lacy, interaction could inspire brilliance.

Joined on this release by bassist Reggie Workman and drummer Andrew Cyrille, Waldron leads the foursome on three of his originals. Lacy and Workman are given one apiece of their own compositions and two Thelonious Monk gems round out the set.

Monk’s “Epistrophy” is played here with more of a swing feel than is sometimes the case. The rendition here is bouncy and cute with just a hint of some spice. “Monk’s Mood” digs deeper, driven by an obvious intensity among all involved Waldron rolls out one of his patented dramatic solos. Cyrille is particularly playful, while Workman provides the sort of strikingly ruminative bass solo that’s not heard often enough on recent jazz releases.

The album is bookended by two rousing Waldron compositions (really three since one is a mash-up). Both “What It Is” and “Snake Out” spark plenty of energy and invention: they inspire the best performances from the leaders. Lacy dives into opportunities to extend his technique, offering plenty of expressive brinksmanship while Waldron responds with some probing runs. The latter piece pauses for a few minutes for a lovely solo reverie by the pianist on his “Variations on a Theme by Cecil Taylor.”

Lacy’s ominous “Longing” and Workman’s spacious “Variation of III” round out a superb disc that reconfirms my high estimation of Waldron/Lacy-led combos

— Steve Feeney

Public Art

Sir Henry Kitson’s Lexington Patriot, 1900. Photo: Abby Janes

Tourists flock to visit the Lexington Green in Massachusetts partly to see the iconic statue that has grown to signify the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World,” known as the Lexington Minuteman. Reflecting the ‘fighting spirit’ that founded our country, the work was created by Sir Henry Hudson Kitson, an English sculptor who lived for many years in the Boston area. Erected in 1900, The Lexington Minuteman stands as a vigilant symbol of the hope and aspirations initiated by the battle for freedom at Battle Green of Lexington, Massachusetts.

With the celebration of the 250th Anniversary less than a year away, the town’s celebration committee (Lex250) has embarked on a series of celebratory projects. One is to commission a sculptural element to be placed on the southside of Battle Green — the piece will commemorate and explain the battle. The challenge: what could creatively stand up to the Lexington Minuteman?

After a rather awkward ‘Call for Entries’ that asked for only a few images of an artist’s or team’s previous public art works, a jury narrowed down the submissions to four finalists. None of the quartet were from Massachusetts. And the most gracious adjective for the four proposals would be underwhelming.

The four finalists include: the well-titled “Spark” by Mark Aeling (MGA Sculpture Studio, from Saint Petersburg, FL ) is a rather confused altar to abstraction; “The Path to Liberty” by Miriam Gusevich (GM2 Studio, of Washington, D.C.) is alleged to be an allegorical garden, but it looks more like an unfinished construction site loaded up with barriers than a road to revolution; “Lex250 Monument,” the most architectural of the entries, by Zaq Landsberg & Thomas Robinson (Studio North, of New York City) sticks an interactive rotating cylindrical bronze sculpture in a rough-hewn, rather clunky stone garden house; and “Reflection” by Jonathan & Saori Ide Russell (Ride Art Studio, of Berkeley, CA) is a self-consciously incongruous kinetic sculpture that looks like a Dr. Seuss seed pod with roots spiraling out from under it. From these candidates, a Sesquicentennial monument will be selected. The result: A Pyrrhic victory? A monumental mistake? Or might there be a welcome surprise ending?

The winner will be chosen by a volunteer selection panel of community members and will receive $250,000 to develop and install their artwork at Belfry Park, across from the Lexington Battle Green. Caveat emptor.

— Mark Favermann

Film

Scott Cohen and Joanna Arnow in a scene from The Feeling That The Time For Doing Something Has Passed.

I was hoping to like Joanna Arnow’s feature debut The Feeling That The Time For Doing Something Has Passed (executive produced by The Florida Project’s Sean Baker) given that it had received accolades after premiering at the Cannes Film Festival. An independent comedy, mostly about someone’s sex life in an urban setting, is a genre that normally might appeal to me. This film is technically proficient and the cast is decent; in different hands its potentially intriguing storyline might have been worthwhile, but I found this excruciating to sit through.

Arnow plays Ann, a young woman in her 30s who drifts from one submissive relationship to the next as she works at a dull corporate job. She occasionally sees her dull family; in terms of plot, that is about it. The first scene is promising. Arnow lies naked on top of the covers next to her older lover Allen (Scott Cohen, an actor I usually enjoy). She grinds against him while quietly reciting all the things she resents about their relationship. It’s not an angry recitation — just matter of fact. When Allen finally responds, he says tiredly, “Could you not?” After a few minutes, I was asking the same question about The Feeling That The Time For Doing Something Has Passed. This mechanical relationship is portrayed via a series of brief scenes: Allen asks Ann to do his bidding, mostly while naked, sometimes wearing BDSM accoutrements. Despite plenty of frank nudity and occasional sexual activity, these interactions are so devoid of sexual energy that the languor felt intentional (and maybe that was the point, and that’s fine). But that didn’t make this any more appealing or interesting.

After a string of other casual submissive liaisons, Ann finally meets someone who genuinely likes her for who she is. Chris (Babak Tafti, great in this role) has no experience with games of dominance and submission. Ann gradually introduces him to this dynamic. Eventually, they may have reached the point that they are interested in finding a more equal romantic relationship and, by the end of the film, it seems Ann could be ready to evolve. Arnow’s dull-as-dishwater dialogue and deadpan delivery embraces the mundane far too tightly — even if they were intended as a sardonic commentary on the colorlessness of Ann’s life. Slice-of-life cinema needn’t be so lifeless.

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: "The Feeling That The Time For Doing Something Has Passed", "The Solitude Suite", "We Are the Leaders We Have Been Looking For", Aba Diop, Debra Cash, Ed Symkus, Eddie S. Glaude Jr., Harvard University Press, Joanna Arnow, Language City, Lex250, Mark Favermann, Myriam Gendron, Peg Aloi, Revolution Sabar, Ross Perlin, Scott Marshall, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Steve Erickson