January Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

A two-CD album that I set aside last year just surfaced in my pile. I downloaded the program notes and was immediately intrigued.

A two-CD album that I set aside last year just surfaced in my pile. I downloaded the program notes and was immediately intrigued.

The youngish tenor Eric Ferring has been doing lyric roles at the Met recently (e.g., Mozart’s Don Ottavio and Puccini’s Pong). This two-CD set is his first release, and he has already come out with a second one, which I look forward to reviewing as well.

No Choice But Love: Songs of the LGBTQ+ Community is an imaginative compilation of songs by gay and lesbian composers (seven men, two women, and a Mexican-American transgender composer, Mari Esabel Valverde). The more recent works often address the challenges of being, or being thought, “different.”

The album opens with the renowned song composer Ben Moore’s hope-filled four-song Love Remained, based on highly personal texts by different authors (e.g., Harvey Milk) about the gay experience in America. It closes with a separate Moore song, composed at the tenor’s request, to a stirring, visionary poem by the Jamaican-American Terrence Chin-Loy.

In between there are items by major figures from a few generations back — Ethel Smyth, Falla, Poulenc, Britten — and more recent ones by Jennifer Higdon (text by Walt Whitman), Ricky Ian Gordon (Langston Hughes), Willie Alexander III (James Agee), and Valverde (Tove Ditlevsen, in Danish).

My favorite work is Jake Heggie’s Friendly Persuasions: four songs imagining the interactions between the composer Poulenc and various friends.

This is one of the most imaginative debut recitals I have ever encountered. Ferring sings with total control at all volumes and at both ends of his capacious range. Madeline Slettedahl is a continuously supportive presence at the piano. The release does not provide the words for the songs. Ferring’s pronunciation is so clear that I rarely needed them, but my Danish is not up to the task for the Valverde songs!

— Ralph Locke

Books

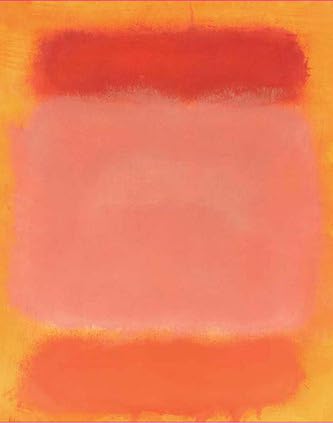

The cover art for Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper.

Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper by Adam Greenhalgh (Yale University Press, 200 pages). This is a catalogue for an exhibition that is currently at The National Gallery of Art, Washington (through March 31, 2024) and will then move into The National Museum of Art, Architecture, and Design, Oslo (May 16 through September 22, 2024).

Greehalgh’s book is a revelatory exploration of Mark Rothko’s paintings on paper that transforms our understanding of a preeminent 20th-century artist.

Following the worldwide chaos, devastation, and human suffering of the Great Depression and World War II, artists started to paint in a challengingly abstract way. Abstract Expressionism was among the movements that explored this new form of visual articulation, which were united in wanting to tear down or deconstruct figurative imagery. The idea was to come up with something pictorially unique; art itself became the object — it was not intended to be a representation of something or someplace, but of color and emotion.

Painter Mark Rothko (1903–1970) is now acclaimed for his often towering abstract paintings on canvas. His luminous artworks convey experiences of joy, despair, ecstasy, and tragedy. These paintings also undoubtedly reflected Rothko’s personal demons, particularly his frequent bouts of self-destructive depression. He is best known as an artist who specialized in immersive canvases; few are aware that Rothko completed more than 1,000 paintings on paper over the course of his career. And that he did not consider these pieces to be preliminary studies, but finished paintings.

In this beautifully illustrated volume, National Gallery of Art curator and art historian Adam Greenhalgh argues that these “ephemeral” works played an important role in Rothko’s aesthetic development and explains how they contributed to his reputation and acceptance. The result is a fresh appreciation of an underrecognized facet of the artist’s creativity. Ranging from his early figurative subjects and surrealist sketches to his better known soft-edged, feathered rectangular colored clouds floating on rectangle fields (the latter often realized at monumental scale), these pictures revise and reshape what we have thought was Rothko’s artistic mission.

Bringing together nearly 100 rarely displayed examples, Mark Rothko: Paintings on Paper accompanies the first major exhibition in 40 years dedicated to Rothko’s works on paper. The book and the show offer a splendid opportunity to look, with new eyes, at this artist’s shimmering, radiant, and distinctively personal painterly statements.

— Mark Favermann

Eva Hoffman, the author of Lost in Translation, has written an odd but interesting introduction to the writings of the great Polish poet Czesław Milosz, who lived through many of 20th century Europe’s most convulsive events, including World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, the Nazi invasion and occupation of Poland, and the Soviet Union’s postwar domination of Eastern Europe. During these tumultuous decades he survived as a peripatetic outsider, living a precarious life in Lithuania, Poland, and France, where he sought political asylum. From 1960 to 1999 he found security in the United States (he taught Slavic languages and literatures at the University of California, Berkeley) before returning to Poland, where he died in 2004. Milosz won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980.

Eva Hoffman, the author of Lost in Translation, has written an odd but interesting introduction to the writings of the great Polish poet Czesław Milosz, who lived through many of 20th century Europe’s most convulsive events, including World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, the Nazi invasion and occupation of Poland, and the Soviet Union’s postwar domination of Eastern Europe. During these tumultuous decades he survived as a peripatetic outsider, living a precarious life in Lithuania, Poland, and France, where he sought political asylum. From 1960 to 1999 he found security in the United States (he taught Slavic languages and literatures at the University of California, Berkeley) before returning to Poland, where he died in 2004. Milosz won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1980.

In On Czesław Milosz, Hoffman, who emigrated from Poland to Canada in 1959, explores the ways in which Milosz’s outsider status shaped his poetry and criticism: his unshakeable allegiance to preserving memories of lost worlds sitting — sometimes awkwardly — with an ambivalent view of postwar culture and what he saw as its intellectual sterility. Hoffman evaluates Milosz’s central literary and political ideas, dissecting the twists and turns in his essays more effectively than the nuances of feeling in his poetry. She’s particularly good at examining Milosz’s see-sawing perceptions of America, a shifting blend of astringency and affection.

One of the volume’s drawbacks is that Hoffman treats Milosz as if he were a sage rather than a multifaceted poet dedicated to asking questions rather than providing answers, a thinker whose life work was dedicated to “a passionate pursuit of the Real.” For example, she asserts that Milosz believed human beings have an “intrinsic moral sense.” But he could ask “Can something or someone be saved? Perhaps only through an awareness of one’s defeats, through nakedness that causes forms to come loose and peel off like old paint.” Milosz’s vision invites the provisional — universals do not withstand scrutiny.

Along with these simplifications, Hoffman tosses in extraneous observations about her past into the mix along with speculation about Milosz’s reaction to trends he didn’t live to see. And she makes a number of questionable political observations, such as her claim that Trump’s election in 2016 could “to a considerable extent” be credited to “working-class worries about increasing automation of work in present-day America.”

Milosz is a major poet and a trenchant commentator whose independence of thought, which skewers the right and the left, remains bracing. (Check out his brilliant study of ideology’s siren’s call, The Captive Mind.) On Czesław Milosz is a fine place to start, but for a more nuanced examination of the poet’s rich and complex vision, turn to Andrzej Franaszek’s fabulous biography, Milosz.

— Bill Marx

Visual Arts

Andreas Ruckers, Harpsichord, Antwerp, 1640. Yale School of Music, Morris Steinert Collection of Musical Instruments. Photo: Christopher Gardner

Ornament, an exhibition on view at the Yale University Art Gallery through February 18, begins with a long quotation from Vitruvius, the first-century Roman architect and theorist. It reads, in part, “Instead of columns, stalks rise; instead of gables, striped panels with curled leaves and volutes. Candelabra hold up pictures, and above the summit of these, clusters of thin tendrils rise from their roots with little figures seated upon them at random with heads of men and animals attached to half a body.… Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been.”

Although the exhibition does not say so, Vitruvius is describing a new style in Roman wall paintings. He does not approve: “It is the new taste that has caused bad judges of poor art to prevail over true artistic excellence.… when people see these frauds, they find no fault with them but on the contrary are delighted, and so not care whether any of them can exist or not.”

Ornament is not a survey of design in world art. It leaves out the intricate geometric decorations of Islamic art and architecture, for example, as well as anything modern. On view are European drawings and prints, along with lavishly decorated keyboard instruments, from the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. This was a period fascinated with all things Roman and several works depict Roman reliefs and other relics. Others are designs for elaborate fountains and architecture or are portraits with intricate borders or even decorative human heads.

Everything is infected with the fanciful and the fantastic, using ornament, as the exhibition says, “as an arena for artistic license, for the imagination to run wild.” Despite Vitruvius, it is likely to delight anyone with a love of visual excess.

— Peter Walsh

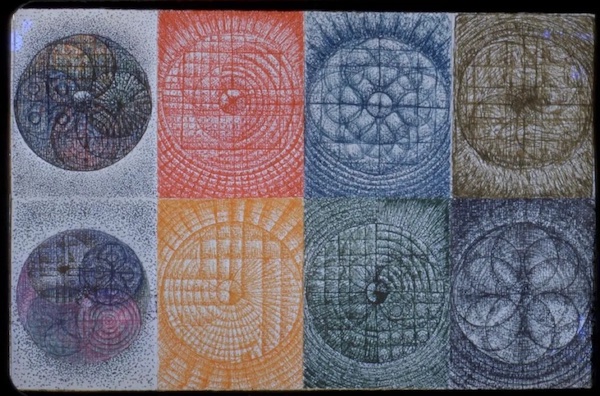

Harry Smith, Abstract film studies (two slides projected alternately), 1951. Film stills (lightbox), 21 7:8 × 33 1:2 (55.6 × 85.1 cm). Estate of Jordan Belson

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith runs through January 28 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Co-curated and designed by Carol Bove, the exhibition is the first solo show of artist, experimental filmmaker, and groundbreaking musicologist Harry Smith, best known for his 1952 compendium of song recordings, Anthology of American Folk Music, which laid the groundwork for the popularization of folk music in the 1960s. The show displays a broad selection of the extant work by this eccentric artist, who passed away in 1991. Over time, much of Smith’s art was lost, tossed away, or destroyed, much of it by the artist himself while in a rage. The exhibition followed the publication of John Szwed’s informative biography Cosmic Scholar: The Art of Harry Smith (Fuse Review). I had just finished the book and attended the show’s opening day. The crowd was small enough to allow me time to comfortably sit with a pair of headphones and watch Smith’s film work.

Film No. 12: Heaven and Earth Magic is an experimental collage short created between 1957 and 1962. Many critics regard it as his masterwork. It is made up of a concatenation of associational images triggered by an unconscious, though sometimes logical, ordering process. It has a very loose story: a woman chases a dog who has stolen her watermelon; she then goes to a dentist and experiences hallucinations under anesthesia. The visuals reflect Smith’s interest in the experiments of Dr. Wildner Penfield, a neurologist whose brain surgery on epileptics was said to have produced visions.

Smith is celebrated for his Anthology of American Folk Music, but the show was primarily made up of his visual work. What’s on view includes examples of his vast collection of unique paper airplanes, folded from flyers and various discarded pieces of paper; several of his string figure sculptures; an untitled animation of Seminole patchwork; and many of his paintings. I listened to Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca” and Charlie Parker’s “Ko-Ko” while gazing at pictures displayed in light boxes (these were film stills; the original paintings have been lost). These experiments in a kind of synesthesia took years to create — the abstract visuals have been structured to correspond with Smith’s perception of the chords and notes in the jazz compositions.

A scene from Harry Smith’s Film No. 18: Mahagonny.

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten‘s showpiece is the two-hour-long Film No. 18: Mahagonny, which took a decade to finish. It is a four-screen film set to the score of the eponymous Brecht-Weill opera. According to Szwed, Smith did not want the film shown in Germany because the singing would be understood there: that would corrupt his intent to juxtapose pure sound with a play of images.

When asked, no one on the Whitney staff knew why there was a boxing ring hanging on the wall at the entrance of the exhibit. According to Szwed, the four screens on which Mahagonny was originally projected in 1980 were set inside a boxing ring mounted on the wall.

— Tim Jackson

Film

Mahershala Ali, Myha’la Herrold, Julia Roberts, and Ethan Hawke in Leave the World Behind. Photo: Netflix

Leave the World Behind, now streaming on Netflix, is a thriller directed by Sam Esmail (Mr. Robot). The film stars Julia Roberts and Ethan Hawke as Amanda and Clay, an affluent couple who rent a luxury house in Long Island for a family vacation. Soon after their arrival, a father and daughter in formal wear, George and Ruth, arrive at the door, insisting that this is their home and, due to an unforeseen emergency, they need to shelter there. Played by Mahershala Ali and Myha’la Herrold (who is excellent in HBO’s Industry), the African-American homeowners understand that their unexpected appearance will be disconcerting for the white vacationers. The racial tension is muted at first, but it bubbles to the surface in due course.

The reason behind the emergency crisis is mysterious, but it has to do with the failure of cell towers: there’s no functioning internet. George seems to know some things about the blackout. He is concerned that they’re all in danger, but it’s impossible to know how widespread the breakdown is given that there is no access to the usual sources of information. An ornery survivalist neighbor (played craftily by Kevin Bacon) claims to know what’s going on, but he is unwilling to help anyone who is “unprepared.” Meanwhile, Amanda and Clay’s teenagers are unhelpful; daughter Rosie (Farrah McKenzie) just wants to watch the last episode of Friends, and Archie (Charlie Evans) is sneaking cellphone pics of Ruth in a bikini. As misunderstandings escalate and physical danger arises, the two families realize that they must find a way to trust each other and cooperate.

Based on the 2020 novel by Rumaan Alam, Leave the World Behind explores the fragility of a world dependent on digital information as it explores how quickly social niceties fall apart during a genuine crisis. There are occasional plot implausibilities and some middling CGI effects, but an excellent cast bolsters an intriguing, suspenseful, and not too far-fetched story whose impending sense of doom feels all too real at times.

— Peg Aloi