Author Interview: “Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age” — Remembrance of Things Past, On Cape Ann

By Mark Favermann

“One of the accomplishments of this book is that it is a capsule history of the art of Cape Ann.”

Cover Art is by Dr. Charles Giuliano, father of the authors.

In Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age (Berkshire Fine Arts, 205 pages with illustrations, $25), sibling authors Charles and Pippy Giuliano reflect on their unique family histories and their personal adventures coming of age in the “tony” and Waspy Annisquam neighborhood of Gloucester, Massachusetts, from the late ’40s to the ’60s. Cape Ann has long been a family place. Their maternal ancestors, the Irish immigrant Nugents of Rockport, homesteaded at Beaver Dam Farm in 1875. Their mother’s paternal line were the Flynns. Both of Charles and Pip’s parents were doctors. Their father was an Italian-born surgeon; their mother was a very New England general practitioner. But neither Charles nor Pip, separated by nine years, followed in the family business.

Europeans settled in Gloucester in 1623, where they encountered the Pawtucket people who had been there for millennia. Nearby on Cape Ann, Annisquam was settled in 1631. The primary industries were fishing and granite quarrying. Today, the economy has morphed into mostly tourism — whale-watching has become a fixture. In the latter half of the 19th century, Cape Ann became a magnet for artists, hosting a vibrant community mixture of painters and sculptors. Over the last century and a half, many prominent artists spent time living and working there.

Inspired by the cultural and social heritage of Annisquam, Charles became an artist, curator, noted arts journalist, and art historian, while Pip became a very talented special needs teacher. This autobiographical narrative, told from both their perspectives, candidly speaks to issues of class, ethnicity, and parent-child discord as it reflects the social and cultural history of a very specific region. The siblings reflect on the trials and tribulations of their nurturing in an uncommon time and place — their strict upbringing led to awkward social interaction as well as youthful and adult rebellion. Charles and Pip were open to questions about what they learned about themselves, and the region, in working on their remembrance of things past.

Arts Fuse: What is your first memory of Annisquam?

Charles: Pip was an infant, and I was 9 during our first summer in 1949. There was a cool reception and insulting comments about our ranch style house, which stood out from all the shingle cottages around it. It was clear that we were outsiders, unwelcome interlopers.

Pip: Some of my earliest memories remain particularly vivid, such as the smell of the fresh wood when you entered the house, the pungent aroma of wet sand streaked purple with sparkling mica. Our mom contracted a ship’s carpenter to construct built-in bunks, with a substantial ladder to climb aloft. They became the special place of dreams. The “bunk room” was my first sanctuary, where I learned to share the bunks with silverfish and spiders. These were early lessons in ahimsa.

The Giulianos touring Windsor Castle in the late 1950s. Photo: Giuliano Family Archives.

AF: What were your best memories of summers in Annisquam?

Charles: To be accepted in Annisquam, one sailed or played tennis. I took to sailing, which I did spring through fall both locally and in a number of regattas. Our family was a bust at tennis.

Pip: Compared to city living on Beacon Street, Brookline, Annisquam was a rustic oasis. It was open space where a kid could roam unrestrained. In the early ’50s, people seemed less obsessed with property ownership. The land was open and contiguous with no restrictions or boundaries for play.

AF: What influenced your future lives the most about your experiences there?

Charles: Pip and I had very different experiences and responses to snobbery and social rejection we encountered. It encouraged me to become an extroverted and independent thinker. I carved out a leadership role among like-minded outcasts and rebels. That was crucial in may establishing a life long anti-establishment, liberal persona.

Pip: Summers in Annisquam gave me the opportunity to explore and trust myself. Out from under the control of my parents, we were loosely supervised.

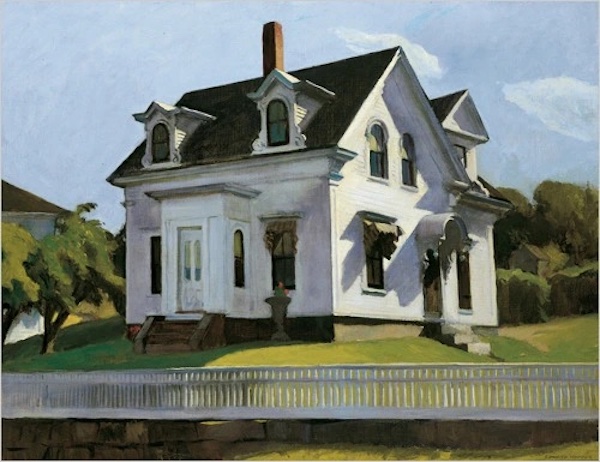

Edward Hopper’s Hodgkin’s House in Gloucester, MA (1928). Photo: National Gallery of Art

AF: In the ’50s and ’60s was there a hard separation between Catholics and Protestants?

Charles: We and several other Annisquam families worshiped at the folksy Sacred Heart Church in nearby Lanesville.

Pip: You could feel the war of the churches. Subtle comments made you feel that you were a lesser individual in this mostly Protestant enclave.

AF: Was there a recognition of class and caste by you both then?

Charles: The dividing line was more a matter of caste than religion. Our parents were accepted as accomplished physicians. Our mother enjoyed many close relationships. Many of our neighbors had been living in Annisquam for generations. The sense of white privilege was unmistakable.

Pip: You definitely were made to understand your place. Many families were connected through marriage, creating dynasties. I was always perplexed why kids from wealthy families often looked like ragamuffins and their sandwiches were thin with no extras.

The Fisherman’s Memorial, Gloucester, MA, by Leonard F. Craske (1925). Photo: Charles Giuliano

AF: Did you feel like insiders (Nugent/Flynn) or outsiders (Giuliano)?

Charles: We both are very proud of our Irish Nugent/Flynn heritage with great grandparents who established a Rockport homestead in 1875. The Nugents at one point wielded political power as the largest land owners on Cape Ann, including all of Good Harbor Beach. The family was swindled out of this legacy. What remains is a condo development — Nugent Farms. My research and writing have done much to restore this forgotten legacy.

Pip: You knew by intuition and outright snobbery that you belonged on the fringe of society. There was little ethnic diversity in the village of Annisquam. A French last name was less problematic than a last name (like ours) ending in a vowel. Growing up, our mom’s Gloucester connection did not come into play in helping to establish our identity in Annisquam.

AF: Considering your age difference, at what point did you two click as siblings/equals?

Charles: Not in Annisquam, but much later, after her college years, we saw ourselves as equals.

Pip: Charles and I were companions from early on. I was a good crew on his sailboat: obeying orders to sit out on the end of the boom. Sometimes he took advantage of my easygoing nature. Showing off for girls, he held me upside down over the rocks as they pleaded for my freedom. I was always part of Charles’s life. He used to come to me for money after hitting up Dad. I kept cash in my bureau drawer available for emergencies: a lesson learned from parents who lived through the Depression era.

AF: What was your father’s impact and pressure on you?

Charles: It took three years of group therapy to recover from my father, who disowned me as an artist. I was able to make peace with him before he died, but I still am burdened by his emotional abuse. That said, my father was a genius with many skills. But he did not understand or support any of my ambitions. My wife Astrid asks why my mother didn’t do more to protect me.

Pip: Of Sicilian decent, my father was a domineering, self-made man. Early on, I learned to tiptoe around his anger and deep freezes. He was perhaps more tender towards me than anyone else in the family. Dad was a sport on many occasions: I went with him to boxing and wrestling matches at the Boston Garden. During summers, we fished off the rocks and painted en plein air. But years later, when I left for college, he reminded me to watch my step or he would employ a detective to follow me.

AF: How was your mother’s relationship with you different than his?

Charles: On Annisquam, she was less engaged. Later in life Mom became a great friend and travel companion. Our road trips were remarkable.

Pip: Mother was a bit cool and aloof. She ran two households and a busy medical practice. Occasionally, she relaxed on weekends. At age 13, I orchestrated a campaign to win my mother’s affection. She had just undergone surgery for breast cancer. The campaign was victorious, and we became great pals.

Winslow Homer’s Breezing Up “A Fair Wind” (1873-76). Photo courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

AF: The chapter on local and regional artists reads a bit like the part of the Book of Genesis that goes on and on about who “begat” who. Many artists are listed in the book. How many were historically prominent? Or were many just members of the successive communities?

Charles: One of the accomplishments of this book is that it is a capsule history of the art of Cape Ann. When I engaged in serious research, I was astonished by the depth of the region’s art community. Many of the greatest American artists summered on Cape Ann, and did some of their most significant work. This summer the Cape Ann Museum is celebrating Edward Hopper and his much less known spouse, painter Jo Nivison Hopper.

AF: Was there a strong connection between you two, your parents, and the artist community?

Charles: Both of our parents took painting classes and created seascapes and landscapes in the local style. I knew of but had little interest in the then superannuated Rockport School.

Pip: My father was a talented self-taught painter. The trunk of his Cadillac was the permanent repository of his oils and easel for painting on scene, wherever that happened to be. As a member of the North Shore Arts Association, he studied with many of the Cape Ann artists: Strisik, Gruppe, Curtis to name a few. He dragged me along to painting demonstrations where he often took notes on color mixing, composition, and technique. Mom showed no interest in painting until her retirement. She surprised us all with her natural talent. In the ’80s and ’90 she studied with the prominent Cape Ann artists of the time. She studied technique from books, taking notes much like my father. She continued painting at the Lake Worth Casino Studio when she wintered in Florida.

The late 19th-century Nugent Homestead Beaver Dam Farm in Rockport, MA. Photo: Charles Giuliano

AF: Did writing this book together bring you catharsis, a sense of closure?

Charles: This has been a loving and affirming experience for both of us. On many levels, Pip is my oldest and closest friend. Over the past year we have had a truly remarkable experience as the chapters evolved. It has taken great courage to reveal a deeply personal history. For me, her writing is rich, evocative, and astonishing. To us both, it’s a fun and lively book with great illustrations. That gives us a great sense of shared accomplishment.

Pip: The book sprang from lengthy phone conversations when the world stood still as Covid raged. Our vulnerability and aging were discussed. During our conversations, Charles prompted me to record some of my travel adventures. It was a pleasant detour to leaf through journals and albums and to stabilize those memories. Then bang — he posted them on his writer’s blog. The collaboration began to take shape, placing our lives in Annisquam as the focal point. Innocently, I jumped on board and here we are, literally bound together.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age, Charles Giuliano, Gloucester MA

An important piece in the 400th Anniversary of Gloucester and Cape Ann: personal, familial and familiar. Cooked not raw.

Charles is a major contributor to 20th & 21st Century New England art history!