May Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Jazz

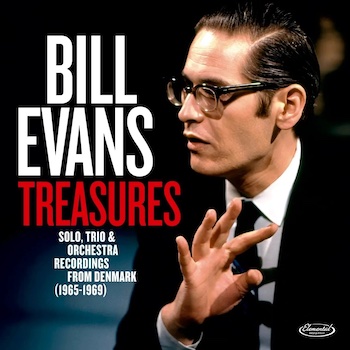

The Danish knew what they were doing: this is pianist Bill Evans captured during what for many is an underappreciated period in his career.

“It’s a sound that keeps going, even though his body is no longer on earth, it just achieves greatness.” So said jazz legend Ran Blake about pianist Bill Evans (1929-1980) in an excerpt from an interview that the booklet for Bill Evans – Treasures: Solo, Trio, and Orchestra Recordings from Denmark 1965-1969 (Elemental Music), the latest batch of “new” recordings of the pianist to be released.

“It’s a sound that keeps going, even though his body is no longer on earth, it just achieves greatness.” So said jazz legend Ran Blake about pianist Bill Evans (1929-1980) in an excerpt from an interview that the booklet for Bill Evans – Treasures: Solo, Trio, and Orchestra Recordings from Denmark 1965-1969 (Elemental Music), the latest batch of “new” recordings of the pianist to be released.

It’s yet another set of previously unreleased recordings, unheard since their original European radio broadcasts in the ’60s. The Danish knew what they were doing: this is Evans captured during what for many is an underappreciated period in his career. They recorded them in remarkably hi-fidelity. I have been drawn to his late period work, this is the sort of release that inspires reevaluation of established preferences.

Evans plays solo and in trios with bassists Niels-Henning Ørsted Pederson (aka NHØP) or Eddie Gomez, drummers Alan Dawson, Alex Riel, or Marty Morrell, and then fronts an orchestra (conducted by and featuring arrangements by Palle Mikkelborg) that combines The Royal Danish Symphony Orchestra and The Danish Radio Big Band (the latter featuring, among others, U.S. ex-patriots Idrees Sulieman (tp) and Sahib Shihab (reeds). It’s a trove of fine music.

The orchestral pieces are mostly Evans compositions that have been thoughtfully fleshed-out. The one that first knocked me over was a take on “Time Remembered” (a tune that is also given a solo and two separate trio run-throughs on the disc!). Mikkelborg accentuates the piece’s noirish feel, injecting the orchestral flourishes in ways that deepen Evans’ melancholy reflection. A suspended close underlines the fateful timelessness of certain times remembered.

Mikkelborg, on his own piece, “Treasures,” adds trumpet in order to reflect on Evans’ involvement with Miles Davis and Gil Evans about a decade earlier. The pianist’s solo calls upon his bop roots as does his work on two bouncy takes of “Waltz For Debby.” The complex line of “Walkin’ Up” recalls Evans’ work within George Russell’s “third stream” experiments.

The solo pieces are a good example of what pianist Matthew Shipp, in his contribution to the album booklet, calls Evans’ “holistic” approach. “You never hear any superfluous part,” notes Shipp. A boppish middle section to “My Funny Valentine” entices without distracting from the sweet sentimentality of the tune. “Come Rain or Come Shine” offers exquisite splashes of color in a tune that Evans seems to inhabit. A trio version with NHØP and Dawson further elaborates on the Arlen/Mercer theme.

Evans staple “Elsa” is given a mid-century shine in a trio take with Gomez and Riel while “Emily,” with Morell on drums, is a swinging, romantic celebration.

Excellent takes, very well recorded — this is a gem among the current crop of Evans releases. May he long endure.

— Steve Feeney

I salute Michael Rabinowitz for following his Muse, doing his own thing, putting out his own records, and stretching the boundaries. But those jazz bassoon solos… I don’t know, man.

Sometimes you hear of some unlikely combination that you think can only be a bad idea that isn’t going to work, and Surprise! It turns out to be a bad idea that doesn’t work. The latest example is Michael Rabinowitz’s album Next Chapter. There’s no question that Rabinowitz has serious chops. He also has serious jazz cred as a founding member of the Charles Mingus Orchestra, plus having recorded with Ira Sullivan, Wynton Marsalis, Dave Douglas, Chris Potter, and Joe Lovano, plus four albums on his own. He’s a fine composer, he has good taste, and he can swing. But he plays the bassoon.

Sometimes you hear of some unlikely combination that you think can only be a bad idea that isn’t going to work, and Surprise! It turns out to be a bad idea that doesn’t work. The latest example is Michael Rabinowitz’s album Next Chapter. There’s no question that Rabinowitz has serious chops. He also has serious jazz cred as a founding member of the Charles Mingus Orchestra, plus having recorded with Ira Sullivan, Wynton Marsalis, Dave Douglas, Chris Potter, and Joe Lovano, plus four albums on his own. He’s a fine composer, he has good taste, and he can swing. But he plays the bassoon.

Jazz can take just about everything you can throw at it, and musicians have wailed convincing jazz on almost every conceivable instrument, from the cowbell to bagpipes. Maybe the bassoon can fit on some Anthony Braxton free improvisation efforts (and Rabinowitz has played with Braxton), but it just doesn’t sound right on straight-ahead jazz.

Pianist Matt King plays with a nice Bill Evans-style touch, and bassist Andy McKee and drummer Tommy Campbell round out a sensitive and flexible rhythm section. The ballad playing, as on Rabinowitz’s title track, is especially fine. Maybe it’s just me, but as soon as the bassoon comes in, it kind of falls apart.

No other instrument, other than perhaps the timpani, carries the baggage of classical music so heavily. Violins, cellos, French horn, all the other instruments (including the oboe, thanks to the masterful Paul McCandless), have successful track records in jazz. But the bassoon, sounding like a duck mellowing out to Mozart, just doesn’t get there for me.

I salute Rabinowitz for following his Muse, doing his own thing, putting out his own records, and stretching the boundaries. But those jazz bassoon solos… I don’t know, man.

— Allen Michie

The dancers and seated patrons were left in a state of satisfied exhaustion at the end of an evening with the John Santos Sextet.

The John Santos Sextet in action at the Freight & Salvage in Berkeley, California. Photo: Brooks Geiken

There was no fooling around on April 1st after the John Santos Sextet hit the stage at the Freight & Salvage in Berkeley, California. The sextet broke into “La Juventud” and from then on we were treated to a Cuban/Puerto Rican dance extravaganza. The dance floor gradually filled up as Marco Diaz on piano, Santos on congas, and Charlie Gurke on tenor saxophone played energizing solos. On the third tune brought on special guest El Mago Del Timbal (The Magician of the Timbales), Orestes Vilató. Orestes is, without a doubt, one of the greatest living timbaleros. His solo on “La Historia De Un Amor” was tastefully brilliant; he has a unique rumbling sound on the timbales, and punctuates it with the crash of the cymbal.

Juan Luis Pérez sang a Danzón-Mambo tribute to the San Francisco neighborhood where Santos grew up, Bernal Heights. Saul Sierra’s bass and special guest Anthony Blea’s violin solos were there to pay proper homage to a fine barrio. Orestes returned for the set closer, “Guararé de Pastora.” Those who got up to dance were mesmerized by his solo and threw up their hands in appreciation.

The second set included “Scheherezada” by Cuban pianist Frank Emilio Flynn, featuring the vocals of Juan Luis Peréz. The bolero “Como Fue,” popularized by Beny Moré, was sung with gusto by José Roberto Hernández. The interplay between the horns, trumpet (Marco Diaz) and tenor saxophone (Charlie Gurke), with the congas and the drums (David Flores) kicked up “Café Con Leche” several notches. The Wayne Wallace and Orestes Vilató composition, “Descarga Fajardo,” a Cuban jam session dedicated to bandleader and flutist José Fajardo, was highlighted by a poignant flute solo by Dr. John Calloway. The evening came to a close with Santos’ congas opening up “Mi Corazón Borincano.” Orestes’ wizardly percussion and Blea’s violin rocked the house once again. The dancers and seated patrons were left in a state of satisfied exhaustion.

— Brooks Geiken

Touring for their latest album, Parallel Motion, Yellowjackets eased into the Shalin Liu Performance hall with evident comfort. You knew right away that something special was coming.

Members of the Yellowjackets (l) Russell Ferrante and (r) Bob Minzer performing at the Shalin Liu Performance Center. Photo: Glenn Rifkin

For the first time in 9 years the Yellowjackets, the innovative, Grammy-winning jazz fusion band, returned to the Shalin Liu Performance Center in Rockport last Friday night. I was there for the 2014 show, and the band’s long-overdue return did not disappoint. These Yellowjackets definitely float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. Touring for their latest CD, Parallel Motion, the group eased into the hall with evident comfort. You knew right away that something special was coming.

Russell Ferrante, on piano and synthesizer, is the lone original member of the troupe that formed 43 years ago as a backup band for guitarist Robben Ford. His longtime mates, Bob Mintzer, the superb saxophonist, and Will Kennedy on drums, were joined by the newest member, Australian bassist Dane Alderson, who replaced Felix Pastorius. The level of musicianship of this quartet is sky-high. With 26 albums and 17 Grammy nominations (two wins), the Yellowjackets is jazz royalty.

In Rockport, in front of a hall filled with their loyal fans, the Yellowjackets showed off its musical dexterity with a cross-section of selections from a very rich catalogue. Alderson channeled the legendary electric fretless bassist Jaco Pastorius (father of Felix), who redefined the role of the electric bass in jazz. Alderson provided an infectious energy, especially on a hauntingly funky solo that shocked the hall. Kennedy, who has performed with Herbie Hancock, Chaka Khan, and Esperanza Spalding, showed off his skills on another solo that triggered a standing ovation. Strong advocates of musical education, Kennedy, Ferrante, and Mintzer teach at the University of Southern California Thornton School of Music.

Opening with “Capetown,” virtuoso saxophonist and electronic wind instrument player Mintzer showed that he had brought in chops for a big night. After more than three decades alongside Ferrante, Mintzer is the perfect front man for the eclectic mix of smooth jazz, R&B, and funk that the Yellowjackets prefers. The veteran has performed on more than a thousand recordings, with the likes of Tito Puente, James Taylor, Randy Brecker, and Eddie Palmieri. If anything, he has gotten better with age.

The set included “Dewey,” a tribute to Miles Dewey Davis, and “Monk’s Habit,” a salute to Thelonius Monk. A highlight was a Ferrante original, “Claire’s Song,” written for his daughter in 1983. Yellowjackets will be performing at Jimmy’s Jazz and Blues Club in Portsmouth, NH on June 18.

— Glenn Rifkin

Popular Music

Samurai Banana doesn’t dwell on the lethargy and decay of affect which come with depression. His album portrays the disease as a crushing, terrifying force that traps its sufferers in a state where they feel like they will never improve.

Samurai Banana looking up . Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Samurai Banana loves wobbly, detuned sounds and jarring shifts in texture. His music bounces along in a queasy manner, like riding a merry-go-round while suffering from nausea. His album Just Tired, is instrumental (apart from a few spoken word passages), but is billed as a song cycle about life with depression. It shares the bleak sci-fi ambience of ‘90s albums like Techno Animal’s Re-Entry and Company Flow’s Little Johnny From the Hospital, which blended hip-hop and noise influences to unsettling, confrontational effect. The CD and Bandcamp download come with a 16-page booklet, which Banana describes as “lyrics for an instrumental album.” Over paintings by his father Richard Gann, Banana fleshes out each song’s mood with flash fiction, although these words never appear on the album itself.

Samurai Banana’s roots in hip-hop can be heard in his booming snares and hi-hat fills (the first minute of “Violent But Friendly” would work as a trap beat), as well as the turntable scratching on “Demon Dancing.” But he fills in the rest of the space with unnerving hisses and electronic zaps. “Oh Shit” is harsh and menacing, filtering and stretching hissing and mocking laughter to demonic proportions. The album is full of sounds which sound almost familiar, yet are transformed and warped. On the title track, for instance, a keyboard flickers in and out as though it’s operating on a drained battery. Just Tired doesn’t dwell on the lethargy and decay of affect which come with depression. It portrays the disease as a crushing, terrifying force that traps its sufferers in a state where they feel like they will never improve.

As the concept suggests, Just Tired ventures into some extremely grim states of mind. “Shattered Glass” samples a man speaking about his suicide attempt. Even in this song, the mood can shift radically: “Wanna Sleep” goes back and forth between frenzied and calmer passages. In the very last seconds of the album, a man muses “I am very proud of my sadness because it means I am more alive.” The peace that comes with the end of a cycle of depression is the most positive emotion Just Tired evokes.

— Steve Erickson

River Glen — progressive folk whose lyrics conjure the romantic sensibility of a modern medieval bard.

River Glen Breitbach’s songwriting style breezily melds folk, pop and rock together, with occasional forays into hip-hop and house, a mélange of traditional and contemporary sounds that is energetic, infectious, and very easy to listen to.

As Above, So Below, the latest album from River Glen, a band led by River Glen Breitbach, an extremely talented young musician who won a prestigious arts grant from his home state, Iowa. It’s also a collaborative work: a short intro styled like a vintage radio announcement says it is a “love letter to Iowa, a patchwork quilt” that involves the efforts of over 150 people, “a love story, a toast, a farewell, a wondering aloud of what it takes to belong.” Glen’s songwriting style breezily melds folk, pop and rock together, with occasional forays into hip-hop and house, a mélange of traditional and contemporary sounds that is energetic, infectious, and very easy to listen to.

The arrangements and production on this album are top-notch. The grant funding was put to expert use: this is what many young independent musicians these days struggle to achieve — a flawlessly-clean and smooth audio creation. But then there are the songs. River Glen is a sort of progressive folky: the song lyrics reflect the romantic sensibility of a modern medieval bard, tinged with bawdy humor and a passionate philosophical vibe. Glimpses of light in the darkness of a world beset with troubles. The instrumentation features Breitbach on guitar, mandolin and banjo; his nimble playing was honed by years of playing with his family’s folk band. Additional players are equally skilled: Justin Leduc on drums, Dan Padley on electric guitar, Blake Shaw on vocals and upright bass, and Megan Roeth on vocals. Roeth’s earthy, mellow voice is well-matched with Breitbach’s especially on “Going Home Again,” which, like many of these original tunes, is a bittersweet paean to life on the road seen as metaphor for finding one’s way in the world: I’m going home again/ No I’m not done roamin’/ But it’s time to see my kin / Tell them where I’ve been. There’s no one else writing songs like these, provocative and poetic, infused with a pagan reverence for nature, haunted by human joys and sorrows, wrapped in music that somehow feels both old as a well-loved forest path and new as the dew on spring grass. (Available through River Glen and via Spotify)

— Peg Aloi

Film

The Plains is one of the most austere tearjerkers ever made, a version of slow cinema that’s more wrenching than meditative.

A scene from David Easteal’s The Plains. Photo: Prime Video

Directed by David Easteal, The Plains (streaming on Prime Video) is an epic of the ordinary. It is as though Chantal Akerman had adapted a John Cheever short story. On one hand, it’s incredibly austere, running three hours and set almost entirely in a car driven by lawyer Andrew Rakowski, playing himself, through Melbourne’s outskirts. On the other, we are served a ferocious torrent of words, mostly about aging and marriage. Easteal, who also plays himself as Rakowski’s co-worker and only onscreen companion, based the film on their experiences driving home from work together during a period leading up to the death of Rakowski’s 95-year-old mother from dementia.

The Plains gradually leaves behind small talk. Rakowski goes into great detail about his family’s history and his present-day life. Despite the film’s minimalism, it’s structured to be a complex drama about its central character. Even the quietest moments are used as emotional punctuation marks. Easteal shot one day a month for a year; he wrote the script during the down time between sessions filming. Rakowski is a non-professional portraying a version of his own experiences, but he gives a remarkable performance. His accomplishment is all the more impressive given that his face is only visible as a tiny image in the car mirror. His voice does almost all the acting for him. Easteal’s script is utterly convincing, but it is is very carefully written out. Few people would be nearly as articulate as Rakowski speaking off the cuff about such difficult matters.

Behind its tightly controlled exterior, The Plains hides a yearning for escape. The film takes place in a car, so Rakowski is physically distant from the people he’s most emotionally connected to. His character is stuck in rigidly defined isolation; he can talk all he wants to, but in a liminal space. Around the two-hour mark, he whips out his iPad and shows Easteal video footage of his mother and his country home. The Plains dramatizes a state in which some of life’s most difficult moments are played out in a context of apparent banality. The deep yearning behind Rakowski’s language only finds visual expression in the occasional overhead drone shots of the fields near his house. It’s one of the most austere tearjerkers ever made, a version of slow cinema that’s more wrenching than meditative.

— Steve Erickson

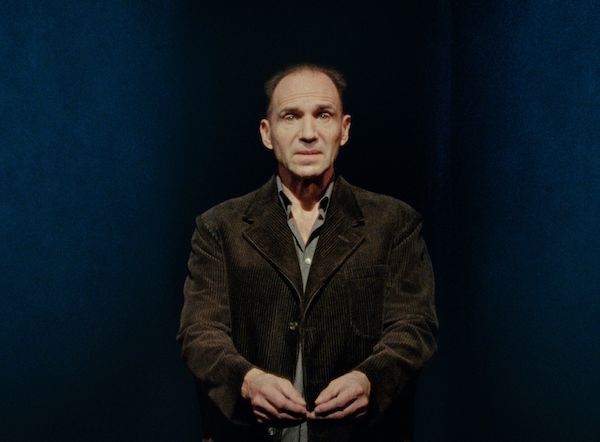

Is T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets a poem we need now? Good as Ralph Fiennes is, I don’t buy it.

Ralph Fiennes performing T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets.

COVID struck artists in different ways. Some were more industrious than others. For the superb actor Ralph Fiennes, national lockdown led him to memorize, and then perform on stage, a dramatization of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, part of which the poet wrote during World War II. Besides being an expression of his evident love of the poem, why spotlight this exercise in Christian contemplation now? “I think it deals with endless and essential questions on the nature of time, the journey of the soul in life,” Fiennes explains. “It’s endlessly mysterious, but there are also ways of speaking it that are conversational and accessible.” His powerfully agile rendition is alert to the poem’s various dramatic registers: he has arrived at an effective mid-point between the two major previous readings – Eliot’s own somewhat stark rendition and Alec Guinness’s plumier, more comforting approach. Fiennes’ theatricality gets at what is, for me, the most fascinating aspect of the poem. Its multifaceted concern with the state of the in-between — its argument revolves around a “still point” between life and death, being and non-being.

Understandably, Fiennes is earnest: there’s not much humor in Eliot’s peon to “the hardly, barely prayable Prayer of the one Annunciation.” But the actor strives for balance: not too bleak or too exultant, not too questioning or too smugly absolute. The first two quartets are given an invigorating spin, at least to my ears: the speaker is trying to persuade us (and himself) of the answers that are to come in the next two. The actor wants to preserve the poem’s sense of mystery, though Eliot assures us that — with the proper faith in Jesus Christ — “All manner of thing shall be well/ By the purification of the motive/ In the ground of our beseeching.” In that sense, Four Quartets is in part about spiritual purification, advising “prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action.”

What action should be spurred by “our beseeching”? Of course, that’s the rub, especially for the masses the speaker condemns as sleepwalking through lives of vacuity: “Distracted from distraction by distraction/ Filled with fancies and empty of meaning/Tumid apathy with no concentration.” What do these people do if they don’t get with the program? Eliot did not value diversity. A notorious passage in 1934’s After Strange Gods makes this clear: “What is still more important is unity of religious background; and reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable. There must be a proper balance between urban and rural, industrial and agricultural development. And a spirit of excessive tolerance is to be deprecated.” Eliot was quickly embarrassed he ever wrote this, but the overall point holds: thoughts and prayers, by all means — tolerance of difference, not so much.

Directed by Sophie Fiennes, the film version is predictably minimal but tasteful, wary of any heavy-handed Christian symbolism, at least that I could spot. There is occasional footage of the sights and sounds of sedate English greenery (nothing undomesticated), some rolling fields and seas also pop up. An ominous bar of blazing red, seen through a doorway, may be the Hell awaiting the unsaved. Fiennes is barefoot and costumed in earth tones; he does some welcome capering (appropriate, given how Eliot interweaves the celestial and secular resonances of dance), strolls meaningfully around a table and chairs, reaches upwards and hugs the wall, looks forlorn and then haggard, sighs and grimaces.

It is a “Shakespeherian” treatment, and those who love the poem will be delighted. As for me, I am with George Orwell — I admire the early Eliot, before he straight-jacketed himself in church doctrine. Though, as I grow old, the verse’s characterization of hapless seniors is accruing some real sting: “Do not let me hear/ Of the wisdom of old men, but rather of their folly,/Their fear of fear and frenzy, their fear of possession,/Of belonging to another, or to others, or to God.” But is Four Quartets a poem that we need now? Good as Fiennes is, I don’t buy it. In “Little Gidding,” Eliot notes “This is the death of earth.” As we face a climate catastrophe of Biblical proportions and then some, The Waste Land offers more valuable guidance: take action as we look for fragments to shore against our ruin.

— Bill Marx

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. is a scrumptious morsel of joy in a movie season that could use it.

A scene Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. starring Abby Ryder Fortson.

This screen adaptation of Judy Blume’s controversial novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. can hold its own among other celebrated mother/daughter films, such as Ladybird, Mermaids, and the acclaimed Everything Everywhere All at Once. Based on Judy Blume’s now classic YA novel, the film does not shy from the realities of puberty or the challenges posed by Middle School. Like the book, the movie will serve as a superb primer for young teens as they navigate those tumultuous years. Standout performances from Kathy Bates, Rachel McAdams, and Abby Ryder Fortson invite the audience to experience the emotional struggles of three generations of women.

The script, written by Judy Blume and director Kelly Fremon Craig, expertly tackles topics of discrimination, adultification, social pressures, mental health, and religious identity. The film offers different rewards depending on age: preteens will cheer on Margaret’s triumph as she grows into a young woman, while adults will mourn her loss of youthful joy and abandon.

There is one glaring weakness in the movie, and that is its treatment of Nancy, a hyper-feminine friend of Margaret’s. The character is not a villain and should not be treated that way — it is too easy to turn her into a scapegoat. She’s a twelve-year-old girl who is frightened of her body and anxious about her future. A person’s journey through girlhood need not be smooth or pristine — judgment is the last thing that should be preached today. The screenplay should have shown Nancy and her ideas about femininity in a more generous, understanding context.

That said, Are You There God? It’s Me Margaret. is a lighthearted delight whose clever quips and jokes reflect real life family dynamics. This is a scrumptious morsel of joy in a movie season that could use it.

— Emma Picht

The documentary is not just about monuments that should be taken down but monuments that should be erected or given greater prominence.

A scene from Valerio Ciriaci’s documentary Stonebreakers.

Although Valerio Ciriaci’s Stonebreakers, a documentary about iconoclasm around the time of the 2020 election, includes the better known attacks on Confederate statuary, perhaps more enlightening are scenes involving memorials to Christopher Columbus. In Philadelphia, not far from tourists posing next to the “Rocky” statue, a local Italian tells a Black demonstrator at a Columbus memorial to “Go pick cotton!” A protestor says she’s Italian too and shouts, “We’re not all like you! We don’t all have hate in our heart!”

As a folklorist points out in New York, the irony is that these working class Italians counter-protestors are supporting an icon elevated against their own interests by “Prominenti,” elite Italian Americans with power and wealth who invested their money and gulled poor fellow Italians into donating pennies they could ill afford to honor a symbol of Western exploitation. Why not build hospitals or schools with this money or memorialize instead working class Italian Americans who fought for social justice and labor rights?

But the film is not just about monuments that should be taken down but monuments that should be erected or given greater prominence, like the sites of the Wounded Knee Massacre or of Gabriel’s Rebellion, in which Gabriel Prosser, an enslaved man inspired by the new republic’s rhetoric of freedom, led a failed revolt against the slaveowners of Virginia in 1800 and was executed.

Similar in its impressionistic, meditative style to John Gianvito’s Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind (2007) and The American Sector (2020), Courtney Stephens and Pacho Velez’s documentary about relics of the Berlin Wall, Stonebreakers also has an eye for the innate absurdity of monuments, such as when a tour guide at the underwhelming Plymouth Rock notes that the Pilgrims must have disembarked one at a time.

Stonebreakers screens as a co-presentation of ArtsEmerson and the Boston Asian American Film Festival, RoxFilm and CineFest Latino Boston at the Emerson Paramount Center on May 19 at 7 p.m. It will be followed by a panel discussion with co-producer and cinematographer Isaak J. Liptzin, co-producer Curtis John, artist and cultural organizer Tran Vu, and Karin Goodfellow, Director of Public Art in the Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture, Boston.

— Peter Keough

Visual Art

New Balance’s Frank Lloyd Wright Broadacre City sneakers.

Wear the Wright thing on your feet?

A newly minted pair of New Balance sneakers, priced at $350 to $400, are available on eBay. A limited edition of the shoes, “created” by designer Ronnie Fleg for lifestyle brand Kith (in partnership with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation at Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona), were made in the USA. They are supposedly based on the color scheme for Wright’s utopian urban concept, Broadacre City. The designer claims that they celebrate Wright’s project. Really?

Broadacre City was never more than a scale model of Wright’s dream of an urban-suburban development concept. He first presented the idea in his 1932 book The Disappearing City. The project was partly conceived out of competition with Le Corbusier’s more influential — but also unrealized — Radiant City (1930) concept.

Like many of Wright’s quirkier designs, Broadacre City was the antithesis of the conventional. It was both a planning statement and some sort of socio-political blueprint. To alleviate population density, each family would be given a one-acre parcel of land from Federal land reserves. In that sense, the notion was the exact opposite of today’s transit-oriented development plans.

Initially, I thought this was some kind of April Fool’s Joke. But the sneakers were marketed in the middle of April. There is no doubt that America’s greatest 20th century architect would have disdained wearing sneakers of any kind. They would have clashed with his customary long overcoat and pork pie hat. And, given how short the egotistical Wright was, he would have demanded two- or three-inch lifts in his athletic shoes.

So, aside from their earth tones, this footwear has nothing to do with Frank Lloyd Wright. As a branding strategy, it is an extremely strange choice for a contemporary sports shoe design. But if these limited edition sneakers take off among the aesthetically cool — who knows? Maybe it could be the first of a series, and Fallingwater Wrights will be right up there with Air Jordans.

— Mark Favermann

Tagged: Allen Michie, Bill Evans - Treasures, Broadacre City, David Easteal, Four Quartets, Frank-Lloyd-Wright, Glenn Rifkin, Just Tired, Mark Favermann, Michael Rabinowitz, New Balance, Next Chapter, Peter Keough, Ralph Fiennes, River Glen, Ronnie Fleg, Samurai Banana, Steve Erickson, Steve Feeney, Stonebreakers, T.S. Eliot, The Plains, sneakers

Where can we see the “Four Quartets”? Is it coming out as a film?

Hi Allen: It is screening in New York right now … not sure about theatrical release, but the film will be available for purchase and rental on Kino Now on June 13 and on all digital platforms on June 27.

In fact, the bassoon goes back a long way in jazz, playing bass lines, section parts and actually soloing. If anyone wants to check out how it sounded in an early jazz context, listen to Joe Venuti’s Blue Four play Runnin’ Ragged (Bamboozlin’ The Bassoon) w. Frank Trumbauer on bassoon and ‘Sippi – Louisiana Sugar Babes with Garvin Bushell on bassoon)

Cool! I’ll check it out.