Arts Commentary/Interview: Some Thoughts on The Climate Crisis and Theater

By Bill Marx

How can we create theater that practices critique and empathy in relation to climate change that simultaneously challenges and lifts us, provokes and provides a muscular hope?

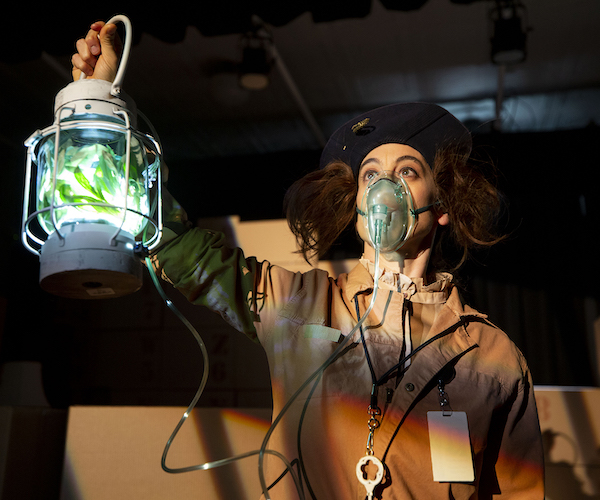

Theatre Artibus co-founder Meghan Frank in character on the set of Inbox at the Savoy in Five Points. March, 2022. Photo: Kevin J. Beaty

“World Has Less Than a Decade to Stop Catastrophic Warming, U.N. Panel Says,” runs a headline in today’s New York Times. “The climate time-bomb is ticking,” said António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, in a statement to mark the launch of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s synthesis report yesterday. “Humanity is on thin ice — and that ice is melting fast,” he added.

But many don’t hear that ticking clock. You would not know there was a climate crisis if you looked at the programming at Boston’s theaters. Here, the ice is (apparently) thick, a runway for shows like the American Repertory Theater’s upcoming revival of Evita to slide on as it moves to Broadway. Don’t cry for me, global warming …

Boston theaters deal with some social concerns. Many of our plays and musicals deal with issues of diversity and inclusion. Our artistic directors regularly hop on soapboxes, pledging to redress inequities in representation. And that is a good thing. But why so little about the climate crisis, an accelerating global catastrophe? It is most grievously afflicting, at least for now, many of the poorest people and countries in the world. Our stages are mum: no dramas about the misinformation campaign being waged by the fossil fuel industry; nothing on what looks to be worldwide criminal political cowardice; silence on the coming extinction of wildlife and insects; nada on the beginning of what promises to be a global immigration crisis; no follow-up to the excellent Sea Sick‘s examination (presented by Arts Emerson in 2022) of the sickening oceans. No one seems concerned enough to raise a ruckus — certainly not our all-thumbs theater critics and arts writers at the Boston Globe, NPR, and elsewhere.

Why the blithe disinterest? Could it be that some of our major artistic institutions receive funding from megabanks, such as Bank of America, which are pumping up the fossil fuel giants to the tune of millions? Could it be that audiences and artists reject “message” dramas, particularly if they suggest that mass inaction will inevitably engender ruination? (Of course, looming tragedy worked well for the Greeks and Shakespeare.) Maybe, as an editor of a Boston-based arts magazine told me, theater companies are doing what they must to get back on their feet after Covid. Give them some time — they will do serious work again. But, as the UN’s report reminded us, that is what we are running out of — time to shape a world worth living in for generations to come. Irreversible damage will be done. Theater should be part of a worldwide effort to alarm, inspire, and challenge. Our stages need to project speculative utopias and dystopias, look for ways to change hearts and minds, and encourage collective action by collaborating with concerned organizations and unions. The theatrical imagination should be tapped to map the way forward. That it is being left in the wings — aside from a workshop or two — is deeply troubling

Perhaps good scripts are scant? As pointed out in the interview below, there are plays that grapple with some of these issues.

I have written about the climate crisis and theatrical paralysis before — and I will continue until the Arts Fuse short circuits. But it is important to hear from a variety of voices, particularly theater professionals who are concerned about the future. What do they think about the detached response of our stage companies? And how can their apathy be turned around?

I sent some questions to local stage artists Debra Wise and David Keohane, who decided to respond as a team. Their bios are below. And please see this interview as an open invitation for other theater people to come forward and contact me. I want readers to hear your thoughts about how the theater can respond to the climate crisis. There is one irrefutable fact: it will become increasingly difficult for theater artists here and elsewhere to ignore the degradation of the world around them. Will we be able to maintain our sanity as nature dies? I would love to see a play about that.

David Keohane is a performer, producer, and educator who is passionate about the stewardship and dynamism of the planet. Originally from the greater Boston area and currently based in the Mid-Hudson Valley, he has experience in agricultural research, dreamwork, puppetry, small-scale farming, adaptation, and outdoor education. www.davidmkeohane.com

Debra Wise is an actor and director living in Cambridge. Currently the project director for Catalyst Collaborative@MIT, a science/theater partnership between Central Square Theater and the Massachusetts Institute for Technology, she is the former artistic director of Underground Railway Theater, which for 30 years toured its original repertoire nationally and abroad before co-founding Central Square Theater. www.urtheaterebook.com

David and Debra have collaborated on multiple theater projects.

Note: The opinions expressed below are representative only of the two of them as individual theater artists, and do not represent positions of any particular theater organizations with which they have worked.

Arts Fuse: Researchers at HowlRound have noticed the low engagement with the topic of climate breakdown by theater practitioners and members of the industry. Not just in Boston but around the country. Why do you think that is, given the enormity of the emergency?

A scene from Sila, 2014. Puppet designed by David Fichter. Photo: courtesy of the artists

Debra Wise and David Keohane: In 2014, when Underground Railway Theater produced Sila, by Chantal Bilodeau, it felt very difficult to find plays to produce that addressed climate change, let alone plays that connected climate change with culture and class (which Sila certainly did, which made it of particular interest to URT’s mission). Perhaps that was because the subject seemed too huge, multifaceted, or abstract to approach through theater, which centers on human stories and loves specificity.

One barrier for both playwrights and producers is guilt. Human beings created our climate crisis, so addressing it means confronting the undeniable realities of our hubris, and of the negative impacts of human innovation. In a sense, confronting our culpability requires critiquing human creativity. Perhaps theaters fear audiences will just feel guilty, be brought down. Who wants that experience in the theater?

And it is difficult to address climate change with nuance and subtlety; there is an understandable tendency to be didactic.

Another issue: the affluent are shielded from the most immediate and disastrous impacts of climate change. Telling essential stories about the experiences of the most vulnerable in the human community requires self-education and authentic empathy for those with life experiences much different from those of the primarily white, middle-class audience of the American regional theater.

But it feels that all of these barriers are falling off at an accelerating rate. Thanks to the work of science writers and activists, it has become easier to parse out the human stories related to climate change. We understand more deeply now how it is driving migration, threatening health, and disrupting cultures. And that it impacts all of us.

As our understanding deepens, there exists an increasingly broad spectrum of ways to address climate change in the theater. Consequently, there are more works surfacing, and with more varied aesthetic strategies.

A course called Writing the Anthropocene at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn explores how writers might better contextualize this time, defined by how humanity’s impact on the world is changing its composition. How do we decenter humans? For instance, take metaphor, which can be very human-centered. What if we invite ourselves as artists to think of natural phenomena as quite separate from us, rather than opportunities for symbolism? What if a volcano erupting has nothing to do with human emotion but is only that? What if “What does it have to do with me?” is no longer a key concern? What new perspectives might emerge.

It is an exciting challenge to find empathy without feeling the need to project oneself and one’s own experiences into the other. This is essential, for instance, in order to activate empathy for the natural environment, for other species.

Theater has a unique position in the arts to allow for nonverbal communication to be represented; so much can be told and evoked in a live performance that is not language driven.

Debra Wise. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Theater has opportunities to help to invite new perspectives, and this perhaps requires new modes of thinking, as well as writing. The Weird and the Eerie, by Mark Fisher, invites us to think about distinctions between seeing something that should not be present in a certain context (the weird) and the failure of seeing something that should be present (the eerie). We are surrounded by images we are used to (trees growing from tiny rectangles in sidewalks, monoculture fields of grain) that our changing perspectives are recalibrating as problematic, as eerie or weird. What do we take for granted that contributes to climate change, that we can effectively investigate in the theater?

And how can we create theater that practices critique and empathy in relation to climate change that simultaneously challenges and lifts us, provokes and provides a muscular hope?

AF: Are there signs in Boston that this indifference may be giving way to concern? And what is driving that change?

Wise and Keohane: Climate fiction is now a subgenre, driven by powerful works like Richard Powers’s novel The Overstory. Similarly, there are an increasing number of playwrights and theaters across the country that are providing titles and practices that directly address climate change. Some of these plays have been recently produced in the Boston area — like The Children (Speakeasy) and Hurricane Diane (Huntington).

Perhaps the pandemic is driving some of that change, making it easier to realize how we are fragile, how we are connected with other species and dependent upon each other. The increasing level of consciousness in other theater communities is bound to continue to impact the Boston area. And because younger people in general are so much more likely to be aware of how climate change is impacting their future, that will continue to be a driver of change, especially as younger people take artistic leadership positions.

AF: What role, if any, should local institutions play in helping theaters deal with climate breakdown, in terms of making facilities and organizational practices greener? What might educational institutions, banks, and philanthropies think about doing?

Wise and Keohane: There is so much waste in our industry because theater is so ephemeral. All theaters need to assess their impact (the way they use and recycle material, the amount of energy they consume), and ideally this would be done in collaboration with their broader community. It is a very welcome sea-change that so many theaters are seriously assessing their practices and commitments in relation to racial justice. Those of us who have been involved in these efforts understand how essential it is to involve staff and board, artists and audiences, local communities and the larger community in the American theater. So we are well-tooled to approach a similar self-audit and strategic shift in relation to climate change and greening our theater sector.

It is terrific that there is a shared props collection, warehoused and run collectively by a number of local Boston-area theaters. How might local philanthropies help theaters share all their resources? To encourage repurposing and minimize the continual practice of building and discarding?

Such change would invite some deep thinking. For instance, is doing away with all printed programs a net positive over requiring that we all have cell phones? How can we discover what hybrid practices are best? Theaters could collaborate to create models to emulate, and this kind of collaboration would also greatly benefit from focused philanthropy.

David Keohane in 2022, working with Cornell University Sustainable Cropping System Lab on a research project experimenting with the efficacy of compatible cover crop and cash crop sequences in no-till agriculture. Photo: courtesy of the artist

AF: Address the thorny issue of theater and greenwashing. How can we distinguish between radical approaches that meet the demand of frontline communities and efforts that are simply about commercial lip service?

Wise and Keohane: To change our fundamental perspectives as theater-makers, we need to not just seek “climate change plays.” We need to move beyond the mentality that, after producing a play that directly addresses climate change, we should tick off the climate change box and move on to other issues. Climate change is woven into the context of our lives. We have the great opportunity to make new discoveries by approaching already existing titles with a curiosity about how they relate to the climate crises. (A great resource for this is 100 Plays to Save the World by Elizabeth Freestone and Jeanie O’Hare, Nick Hern Books, 2021).

It would also be useful if theaters used every production as an opportunity to do self-reflection about what has been learned, and how that might impact practice. Again, in the theater communities in which we have worked, there is an increasing sophistication about how to do this in relation to racial and gender justice. How about environmental justice? Could producing a play like Hurricane Diane lead to deeper feelings and cognition about the environment, and inform a further greening of practices? It is a missed opportunity to leave a project without really assessing, across a theater community, what has been learned before moving on. And we are aware of how difficult this kind of assessment is in the nonprofit theater sector. As artists, we are ambitious and are always working beyond our capacities, so it is both an interesting and real question: how do we create space and time for such community learning?

Perhaps convening a Boston-area theater symposium or conference could help us collectively approach these questions as a community. In real time, and face-to-face.

AF: You have been reading plays that deal with the climate breakdown. What are some of the strongest scripts that you have come across — and why are they effective?

Wise and Keohane: We have mentioned a few above. There should be more plays like these, that invite engaging with climate change in relation to our ways of knowing, of seeing — to provoke our taking new perspectives. And theaters would do well to invite public engagement with the questions raised.

Wise and Keohane: We have mentioned a few above. There should be more plays like these, that invite engaging with climate change in relation to our ways of knowing, of seeing — to provoke our taking new perspectives. And theaters would do well to invite public engagement with the questions raised.

Donmar Warehouse has recorded a terrific podcast series, Climate Conversations, bringing together theater directors and climate change scientists and activists, that could be a useful model for local conversations.

Blame is a tricky place. Perhaps context is all-important in determining how a play that lays blame can be received in a way that is generative of positive action. It would be great to see a production of The Trials, by Dawn King, in which adults are found guilty by young people for their lack of care and foresight. Can that same play generate positive activism, inspiration to take responsibility for a brighter future? The producers in England seem to think it could.

AF: In a HowlRound essay, Thomas Peterson argues that “the climate crisis demands new, locally specific plays to respond to the unique challenges of the place in which they are created and performed. After all, climate change impacts different places in different ways and at different times, challenging the very possibility of universal climate stories.” Do you agree?

Wise and Keohane: Yes, localized stories allow audiences to see themselves reflected, offering them opportunities for understanding local change, for embracing more agency and, thereby, moving forward with hope.

The Oysters by Miranda Rose Hall was performed in Beacon, New York, at the Hudson River, which used to be full of oysters. The play embodies the oysters and their plight. (Oysters are currently being reintroduced into this ecosystem.) Every bio-region will experience its own climate-related breakdowns. Wouldn’t it be interesting to commission a playwright and a scientist to research local phenomena, and develop short plays as a first attempt at getting inside them, through theater and as a community? A community public art practice — through theater?

There are companies whose essential identities are shaped by their environmental commitments. For instance, The Only Animal in British Columbia only produces its shows out-of-doors: its mission is to create immersive theater generated by a deep engagement with place. Its artistic director, Kendra Falcone, spoke in a webinar about how, in somatic therapy, it has been found that the heart moves seven times more slowly than the mind; if storytelling is a way to the human heart, perhaps we need to imagine new, intentionally slower strategies for engaging our own hearts and the hearts of our audiences and of our communities.

Editor’s Note: Miranda Rose Hall’s A Play for the Living in a Time of Extinction will be performed at London’s Barbican Theater, from April 26 through 29.

Safie Martin Yé performs in Miranda Rose Hall’s A Play for the Living in a Time of Extinction at Théâtre Vidy in Lausanne Switzerland, 2021.

AF: Is there any indication that theater practitioners and members of the industry are becoming more politically engaged regarding the climate breakdown? Agit-prop theater has traditionally been involved in protests. In this case, one of the targets would be the power of the fossil fuel giants.

Wise and Keohane: The Only Animal did partner with an antilogging company to help save low-lying rain forests in British Columbia. And there are many examples to be found through Climate Change Theatre Action which encourage local theater artists to connect artistic work with direct action.

AF: What lessons are there in the work of the Underground Railway Theater for creating stage work that addresses the climate crisis?

Wise and Keohane: Theaters need to (and some are certainly doing this) work in connection with others — with scientists, with activist organizations, with communities — to both educate themselves in the course of making a production and to curate community conversations. Underground Railway Theater’s decades of touring — especially between 1980 and 2007 — provide models for that kind of work. The process always began with our theater moving into a period of learning. Before creating Sanctuary: The Spirit of Harriet Tubman, which explored connections between the Underground Railroad and the Central American Sanctuary Movement, our director accompanied a caravan of refugees. Before we began devising Home Is Where, everyone in the company volunteered to work in homeless shelters. Perhaps we could benefit from an acknowledgment that we all need to find hands-on ways of learning about climate change, and that we will discover how new knowledge can impact our practice, probably in surprising ways.

A final thought

Recently, in a New Year’s edition of Climavor — a podcast that investigates connections between climate change and agriculture — an invitation was extended for all of us to find something this year to change your mind about, and to consider that ability to change your mind a badge of honor. As artists, we know (even if we periodically forget) that we need to practice this. Perhaps reconnecting with that commitment will enable us to better engage with climate change.

PS from David Keohane:

A link below to a helpful illustration of ways (“three modes of engagement”) to make climate art.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.