Culture Vulture: Orhan Pamuk At Harvard

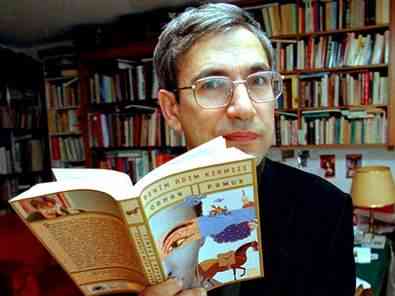

Nobel prize-winning author Orhan Pamuk -- With Book in Hand

A friend of mine who used to teach at Harvard says, “the place is filled with pompous people who think they have to be the smartest and most sophisticated in the world — at least in their field,” so it was a delight this afternoon to hear the unpretentious and visibly agitated Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk give the Charles Eliot Norton lecture in Sanders Theater.

Pamuk is one of the youngest writers to have received the Nobel Prize for Literature, the author of eleven books of fiction and non-fiction that have been translated into 56 languages. It seemed to me that Harvard was lucky to have him visit but Pamul began his talk by noting his “debts” to the institution: his translators, publisher and agent, it turns out, are all “from Harvard” as well as the Turkish and American literary critics who have written most extensively about his work. When an Indian student from Calcutta asked about the method and mentors he had experienced in studying literature in Istanbul, Pamuk replied quickly: “I had no mentors. I was an autodidact who went to bookshops and bought books in an accidental way. To say this in this place of learning is dramatical [sic]– but that’s the way it was.”

His six lectures (he’ll give five more over the coming weeks) are grouped under the heading “The Naive and Sentimental Novelist,” taking off from the the title of Friedrich Schiller’s essay On Naive and Sentimental Poetry. This first lecture explored “What Happens to Us as We Read Novels?” and it was interesting not only to hear a writer describe what happens to him as he reads novels but to do it in language very different from the one western literature teachers and writers use when they talk about literary art.

Pamuk talked about entering imaginary worlds so vivid that we confuse them with real life, books that evoke reality and authenticity so powerfully that we are as loathe to finish them as we are to wake up from a satisfying dream. Unsurprisingly, Pamuk finds Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina the world’s greatest novel “for its lucidity, its observations of daily life, because it’s so real. I feel jealous reading it.” He used no psychological references at all, although some of the reader’s “operations” he alluded to translated to me as Pamuk’s way of describing what we would call “unconscious” and “conscious” process.

“Novels are second lives — like dreams,” he said. Reader as well as writer, in Pamuk’s view, are like automobile drivers, in that they forge ahead on what we would call “automatic pilot” without much awareness of what “operations” they are, in fact, performing as they follow the road. Taking his cue from Schiller, Pamuk divides novelists into the “naive” and the “sentimental” — confusing terms for the twenty-first century. By “naive,” Schiller meant poets like Goethe, whom he -perceived as serene, spontaneous, naturalistic, and child-like in the certainty of their ideas and perceptions. The “sentimental” poet, on the other hand, is reflective, doubts his abilities, is suspicious of what he perceives and burdened by artificial, extraneous concerns.”

Pamuk was a painter before he turned to writing and his talk was peppered with references to the visual arts. Reading a novel for him is like “entering into a landscape painting” where we see a world through both the eyes of the writer and the eyes of his characters. We read on to see what happens next but also to soak up the atmosphere of another world, our minds constantly searching for meaning and motive. A novel, in Pamuk’s view, depends on a kind of complicity between writer and reader: “To derive pleasure from a novel is to transform words into images in our imaginations.”

Orhan Pamuk belives that novels address the meaning of life or what it is like to live.

As he reads, Pamuk contends, the reader is wondering: what part of this narrative is based on real experience and what part is invented? Does the story conform to what we know of real life? How do all the parts fit together? A search for the “hidden center” is, Pamuk argues, what sets the novel apart from other art forms. And that center must in some way address the meaning of a life or what it’s like to live.

Pamuk reminded me of what I so often forget when I read only Western literature: that language conditions representations of life even more than storylines. I’m not sure I entirely understood some of what Pamuk had to say and didn’t agree with parts of it. But it was bracing to listen to a writer talk about writing without any of our lit-crit jargon and to hear what happens to Pamuk when he reads novels.

Helen Epstein is the author of “Joe Papp: An American Life” and “Children of the Holocaust.”

I totally agree that the speech was wonderful, totally unpretentious and genuine with no intimidation of the kind of education he did not have but yet ready to give and share what he had. I can only hope that the crowds who came to hear him yesterday will go back and read him systematically starting with his very first book, White Castle, ending with his latest, Museum of Innocence, which is for me the very best of all… I may add that I was also very impressed with the introduction by Homi Bhaba. Both were both marvelous and cannot wait for the remaining five lectures.

As to the audience Orhan Pamuk attracted yesterday at Sanders Theater, I can not help share one observation. When I saw Professor George Cabot Lodge II of the Harvard Business School in the audience, I was reminded of what I heard 30 years ago when I first came to this town: “And this is good old Boston, the home of the bean and the cod, where the Lowells talk to only Cabots, and the Cabots talk only to God.” Apparently this saying is no longer true, the world has changed immensely and Professor Cabot Lodge was happily listening to a Turk!

I checked the site for the summary of Orhan’s second lecture which was even much better and wonderfully delivered than the first one… I can briefly say that Orhan P. talked about the created characters who lived some his life experiences and even more in this novels. His latest book, Museum of Innocence, brilliantly portrays my own era, more precisely, my youth in Turkey with its social mores and political climate. As I read it, I relived those years with a strong familiarity and nostalgia. I do not feel the need any more to explain myself, or the habits of my people, to any of my present family members, husband and children, and friends… I will simply tell them to read Orhan’s latest book. I very much hope that the English translation is equally good as his Turkish. I can only thank him for having produced such a wonderful book. I just loved every word of it!

“Novels are second lives — like dreams.” I love this phrase.

I think the SNOW is the best (Middle East) book I’ve ever read. I love his style.

I have already read 3 novels by Orhan Pamuk namely Snow, My name is Red and Museum of Innocence and am presently reading Istanbul. Of these I liked Snow the best.To me Orhan Pamuk is a wonderful writer. I do not know why he dragged out the novel Museum of Innocence so long, yet his style of writing did not allow me leave reading the book at any time. His similies and metaphors are strikingly original and beautiful and poetic at the same time. I look forward to reading more books from Pamuk.