Visual Arts Remembrance: Pop Art Icon Claes Oldenburg Dead at 93

By Mark Favermann

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen’s work can be found in the collections of major modern art museums throughout the United States and Europe.

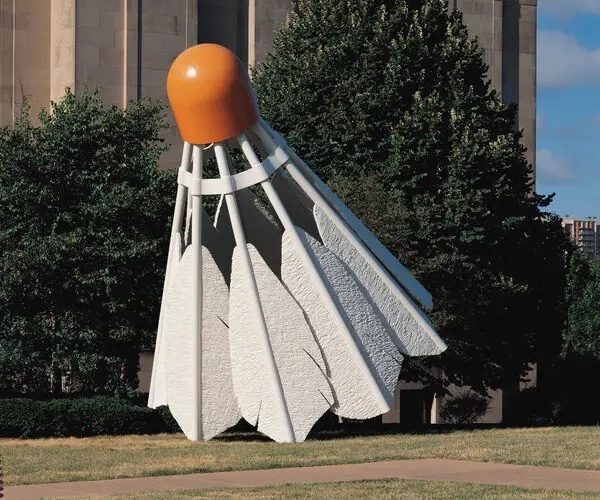

Shuttlecocks by Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, a series of four sculptures on the grounds of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo. Photo: Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Claes Oldenburg, along with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, was one of the great American trio of Pop Art artists. He died at 93 in Manhattan on July 18. Though a gifted draftsman, the artist is best known for his cuddly “soft sculptures” and his gigantic steel sculptures of everyday objects. He not only transformed the mundane into the monumental — he added a sense of mystery, even ambiguity. I met him once during the ’70s in an elevator in SOHO while I was visiting various galleries. He was both serious and affable. We exchanged pleasantries. I told him that I just was given a show at a nearby gallery, and he congratulated me. He congratulated me. That was in the ’70s.

In the ’60s, before he became associated with the Pop Art movement, Oldenburg created many happenings and performance-related productions. Calling his shows the presentations of “Ray Gun Theater,” the performances frequently included a cast of colleagues, including artists Lucas Samaras, Tom Wesselman, Carolee Schneemann, and Richard Artschwager. Oldenburg’s first wife, artist Patty Mucha, was a major part of these stagings. (She also sewed many of Oldenburg’s early soft sculptures.) Oldenburg’s in-your-face, satirical, and humorous approach to art was his sardonic response to the prevailing cultural fashion for profound ideas. In 1962, Oldenburg rented an empty shop on Manhattan’s Lower East Side to exhibit The Store, a month-long installation stocked with “soft sculptures” in the form of consumer goods.

No doubt influenced by Marcel Duchamp’s “readymades,” Oldenburg’s sculptures were handcrafted rather than store-bought. The artist wanted them to be, as he put it, “just as mysterious as nature.” These famed “soft sculptures” were initially made of canvas and later vinyl. They were filled with foam. His humorous Floor Cake and Floor Burger, both from 1962, led to a Giant Toothpaste Tube and then an entire Bathroom, which was installed at the Museum of Modern Art in 1969. Yet, while he was developing his cushy pieces, Oldenburg began to consider creating bigger, grander outdoor projects.

By the late ’60s, his artistic vision was focused on creating monumental pieces. His proposals indicated he was interested in erecting permanent monuments, but the tongue-in-cheek sketches and prints suggest that his impish sense of humor overwhelmed pragmatism. Such project “proposals” included a Fan in Place of the Statue of Liberty and a Design for a Tunnel Entrance in the Form of a Nose. His weird notion that Scissors in Motion should replace the Washington Monument was essentially a mocking gesture.

Spoonbridge and Cherry at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. Photo: Minneapolis Sculpture Garden

The first completed “Colossal Monument” was Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks. It was a giant tube of lipstick (fabricated in vinyl) mounted on tractor wheels. The image’s over-the-top phallic overtones lampooned America’s military/industrial complex as well as the Vietnam War. The piece was set on Yale University’s campus in 1969 at the high point of protests against the war. The administration moved the piece’s location; it was eventually fabricated in steel in 1974 and installed at Yale’s Morse College’s courtyard.

From that point on, all of Oldenburg commissions were permanent, and he cultivated an international following. He collaborated on these monumental projects with his second wife, Coosje van Bruggen. A staff member of Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, van Bruggen met the artist after he and Mucha divorced in 1970. Their first collaboration, 1976’s Trowel I, was an oversized garden implement installed on the grounds of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands.

Clothespin, a 45 foot high steel sculpture celebrating the US Bicentennial in Philadelphia. Photo: Caitlin Martin, courtesy of The Association for Public Art

Married in 1977, the couple collaborated on more than 40 projects, including Spoonbridge and Cherry (1985 to 1988) at the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden and 1991’s Giant Binoculars, which was incorporated into Frank Gehry’s design for the Chiat-Day Building in Venice, California. Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s work can be found in the collections of major modern art museums throughout the United States and Europe.

The most prominent of Oldenburg’s monumental sculptures include 1976’s Clothespin, a 45-foot-high, 10-ton black steel sculpture, complete with a metal spring that explicitly celebrates America’s Bicentennial; Shuttlecocks, a series of four sculptures on the grounds of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri; and 1977’s Batcolumn (or Bat Column), a 101-foot-tall sculpture in the shape of a baseball bat standing on its knob. Set in front of Chicago’s Harold Washington Social Security Administration Building, the sculpture consists of Corten Steel, painted gray, arranged into an open latticework structure. A plaque on the sculpture reads, “Oldenburg selected the baseball bat as an emblem of Chicago’s ambition and vigor. The sculpture’s verticality echoes the city’s dramatic skyline, while its form and scale cleverly allude to more traditional civic monuments, such as obelisks and memorial columns.”

Van Bruggen died of breast cancer in 2009 at the age 66. The artist’s brother, Richard Oldenburg, Director of the Museum of Modern Art (1972-1994), died in 2018 at the age 84.

Born in Stockholm on January 28, 1929, Oldenburg was the son of a diplomat who had postings in London, Berlin, Oslo, and New York before he was appointed in 1936 as the Swedish Consul General. He grew up primarily in Chicago and eventually studied literature and art history at Yale University from 1946 to 1950. Returning to the Midwest to study at the Art Institute of Chicago in the early ’50s, Oldenburg worked for the City News Bureau of Chicago, where one of his duties included drawing comic strips. Interestingly, he was the only major Pop Art artist who drew comics professionally.

Mark Favermann is an urban designer specializing in strategic placemaking, civic branding, streetscapes, and public art. An award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002 has been a design consultant to the Boston Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is contributing editor of the Arts Fuse.