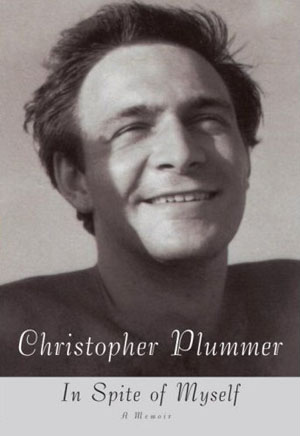

Book Review: Christopher Plummer Recounts His Life

By Caldwell Titcomb

There are those who have proclaimed that Christopher Plummer is the greatest classical actor in North America. There is certainly no gainsaying that he has for some time been in the tiny group at the top of the acting profession. Now as he nears the age of 80 he has brought forth In Spite of Myself: A Memoir (Alfred Knopf, 648pp.).

This huge autobiography is crammed with details. Plummer must have an extraordinary memory or carefully kept diaries – perhaps both. Hundreds of people, well known and unknown, pop up in these pages briefly or extensively. He does not spare himself, admitting to constant carousing throughout the first half of his life. From what he repeatedly tells us, it is a miracle that he did not succumb to cirrhosis long ago. But the woman who is now his (third) wife issued an ultimatum: she would not date him unless he “cut down on the booze.” Along the way he contracted hepatitis, sciatic paralysis, and pericarditis. But he always made a full recovery.

His many jobs over the years – especially movies – took him to a host of foreign locations, and he is good at describing geographical milieus. A Rachmaninoff piano recital led him to become an ardent pianist. Later he would be a fan of bullfighting in Spain (a passion he shared with drama critic Kenneth Tynan, who wrote a book on the subject).

Although he talks about some of his film and television assignments, he discusses almost all his theater work. Near the book’s end, he says, “No matter what I do between, the stage always beckons and gets me every time.” The Toronto native made his debut at 16 in Mauriac’s “Asmodée” with the Montreal Repertory Theatre, for which he played Oedipus in Cocteau’s La Machine Infernale two years later to great praise. And he was on his way.

He saw Sir Donald Wolfit (1902-68) play King Lear, and says that he was, “for the first time, in the presence of greatness.” He cherishes being cast in a show with Edward Everett Horton, whose “polish and indisputable mastery of timing were light-years ahead of” other comedians. “The prime lesson…was just how real, natural and true one had to be in order to make comedy the supreme art that he proved it was.”

In 1952 Plummer appeared in seven plays at the Bermuda Repertory Theatre, including The Royal Family. The play’s matriarch was the formidable Florence Reed (1883-1967), who “had the deepest, most resonant voice I have ever heard in man, woman or beast – deeper than Paul Robeson’s, I swear.” He’s quite right. I knew Reed, and happened to see this production in Bermuda. (In the 1946 The Winter’s Tale, she was the most powerful Paulina I have ever seen, and ran off with the reviews.)

Eva Le Gallienne, “an actress of high intelligence and power,” in 1954 gave Plummer his Broadway debut, in “The Starcross Story,” which opened and closed the same night.

The next year Plummer was Jason to the Medea of Dame Judith Anderson, who was “electrifying…a tragedienne of the first order.” His “first big success” was in Anouilh’s The Lark (1955), adapted by Lillian Hellman, who at the time was “certainly the most dominating writer of either gender – the only one to have total casting approval over all her scripts.” The show’s star, Julie Harris, “is, without question, a national treasure and for more than fifty years has continued to illumine, strengthen and hold together what has now become the fragile fabric of our theatre. Anything short of canonization would be a colossal snub.”

It is fascinating to see all the verdicts he has about those in the profession. He has much to say about Jason Robards Jr. (a sometime colleague and drinking buddy), who in The Iceman Cometh gave “one of the most dynamic and shattering performances I have ever seen.” (It must have been a special pleasure in 2002 for Plummer to receive the Jason Robards Award.) Katharine Cornell “remained always the same – fine, noble, sympathetic.” Frances Hyland’s Ophelia was “the one that was to attain tragic heights.” Elia Kazan “was certainly the very greatest director of tragic drama I have ever worked with.” “Mr Fair Lady,” he says, “is still, arguably, the most perfect musical ever conceived.” Sir John Gielgud was “perhaps the greatest verse speaker of the last century….and possibly the most modest and least selfish of performers ever to grace our profession.”

Plummer portrayed Pizarro in The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1965), which “I still think is the best of Peter Shaffer’s writing” (so do I). “Orson Welles was never one person; he was, quite simply, a crowd.” In 1967 Plummer was Antony to the Cleopatra of Zoe Caldwell, “whose four-octave range could summon up an incredible variety of tones….this performance was to reach greatness.” Sir Anthony Hopkins is “a mimic of sheer genius.”

Plummer agrees with most that Sir Laurence Olivier was “no great shakes as a director.” But as an actor he had everything except pathos. “To have pathos one must be born with it. Ralph Richardson had it in spades; so had Brando and Chaplin; so, I believe, had Chaliapin and the great Salvini.” When Olivier filmed King Lear at the end of his life, he told Plummer, “I’m not very good in it, you know. I was so bloody weak they had to lift me onto my horse.” Plummer agrees it is poor. But he termed Olivier “the greatest theatrical animal of the century.”

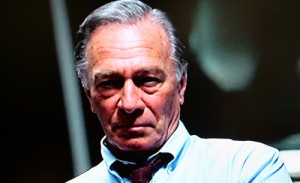

Plummer as Mike Wallace in The Insider. Photo: Hal Drucker.

I did not find many factual errors. The Boston tryout of The Lark took place at the Plymouth Theatre, not the Colonial. Cherry Jones’ Lady Macduff was not her Broadway debut but her second Broadway role. In The Oresteia Plummer’s Clytemnestra was “that powerhouse of lady performers, the statuesque Irene Worth. Irene, who spoke the English tongue with more precision and perfection than most Brits, was, ironically, an American….This had not deterred her from taking out British citizenry and becoming one of England’s very finest classical actresses. Much later she would grace the Honours list as a Dame.” Worth was a dear friend of mine, and this is what ought to have happened. But she never relinquished her American citizenship and was thus ineligible to be created a Dame. The queen, however, did make her an honorary Commander of the British Empire. Plummer asserts that Macbeth is “the shortest of all Shakespeare’s plays,” whereas The Comedy of Errors is the shortest and Macbeth the fifth shortest.

In such a lengthy tome one is not surprised to find a modicum of small slips and typos. Here is a sampling. The violinist Mischa Ellman (p. 35) was Elman. The actor Paul Lucas (120) was Lukas. Alec Guiness (165, 334) was Guinness. Fritz Weaver and Hurd Hatfield did not both play Julius Caesar (173); Weaver’s role was Casca. The Austrian waltz called the Lendler (404) should be Ländler. The wonderful film Garden of the Fitzi-Continis (434) should be Finzi-Continis. Tennessee Williams’ Gnadiges Fraulein (460) needs a pair of umlauts. The noted actor Marc Ryland (487) is Mark Rylance. The celebrated tenor Bjeurling (537) was Björling. Playwright Sam Shepherd (620) is Shepard.

Plummer has appeared on Broadway sixteen times, for which he has received seven best-actor Tony nominations, winning for the musical Cyrano (1974) and the one-man Barrymore (1997). Over the years he has tackled more than a few Shakespearean roles – including both Mark Antonys, Henry V, Hamlet, Leontes, Benedick, Richard III, Macbeth, Iago, and King Lear.

Lear, he says, “is not Mount Everest! Perhaps the play is but not the role. Richard III is much more vocally and physically challenging. Hamlet is monstrously more daunting.” (These two are the longest roles in Shakespeare.) After Lear, what is left to do? Plummer mentions Falstaff, Malvolio, Jacques, and “old Prospero, and as a last resort, perhaps [Shaw’s] Methuselah or, God knows, even God.” Since this book was published, it has been announced that Plummer will undertake Prospero at Canada’s Stratford Festival next year.

It should be noted that the book is not restricted to people. An important component is provided by Plummer’s dogs, who are the cause of some of the most moving writing in the tome. It is no accident that four of the five dedicatees are Briggie, Rags, Toadie, and Paddy – remembered “with gratitude and love.”

The book has one major flaw. There is no index at all. For a writer who has thought about and encountered hundreds and hundreds of persons named in the text, someone should have compiled a thorough index of proper names with page references. I had to attempt fashioning a partial index for my own use. One might compare this with the excellent index provided in the just-published autobiography by Sir Antony Sher, Beside Myself: An Actor’s Life.

Another mildly annoying feature of the Plummer book is the absence of specific dates. There are some, to be sure, but not enough. You might think that in a tome of this size Plummer would have stated the exact date of his birth. In fact, there has been some dispute about that date, a number of Canadian sources giving December 13, 1927. Other references indicate December 13, 1929. In such cases, it is usually wise to go with the earlier date. If the claim that Plummer was born on a Friday the 13th is true, then the 1929 year would be accurate. I am inclined to go with the later year and allow Plummer to reach and celebrate the big eight-oh this winter.

To end on a laudatory note, I can report that the book is exceedingly generous with illustrations. These include three of the priceless caricatures by Al Hirschfeld, bringing the total to 182. The photos add enormously to the pleasure of going through a tome packed with engrossing material about a career of more than sixty years. Now on to Prospero.

This review glistens with remarkable scholarship. There can’t be many writers capable of nailing so many errors among the trees — while passing benevolent judgment on the Plummer forest. Applause, applause for Dr. Titcomb.

Perhaps Plummer confused actor Rylance with dear old “Dadie.” But then again, he was “Rylands” not “Ryland.

My vote for “what’s next?”…

Plummer MUST play James Tyrone in Long Day’s Journey Into Night!

Great review. For the record, there are a great number of references to the violinist as Mischa Ellman. For example, this announcement of a concert with the Philadelphia Orchestra in Billboard magazine in 1950:

http://books.google.com/books?id=4B8EAAAAMBAJ&pg=PT11&lpg=PT11&dq=mischa+ellman&source=bl&ots=W3xlRQf3Xz&sig=DktqfAP5V92YYGmPByOcF09nw4M&hl=en&ei=cAoCS6iPHo-BnQffg5yLCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&ved=0CBsQ6AEwBTgK#v=onepage&q=mischa%20ellman&f=false

Originally a Russian name after all, so perhaps Plummer can be given a pass on that one.

Some squibs in Billboard magazine hardly constitute a reliable source. All major biographical references give his name as Elman. He became a U.S. citizen in 1923, and used the Elman spelling. The headstone of his grave gives Mischa Elman/Helen Elman.

We are reading this book right now and the typos are driving us nuts. Things like “peak” when he meant “peek,” “loathe” for “loath,” “reek” for “wreak,” Uriah “Heap” and even misspelling Martin Bormann’s last name. And look how many more you found! Does no one edit any more?