Visual Arts Commentary: Reordering Design Priorities Through Biometric Research

By Mark Favermann

The cognitive architecture approach espoused by the Human Architecture and Planning Institute is applying a welcome new paradigm that responds in a fresh way to the built environment.

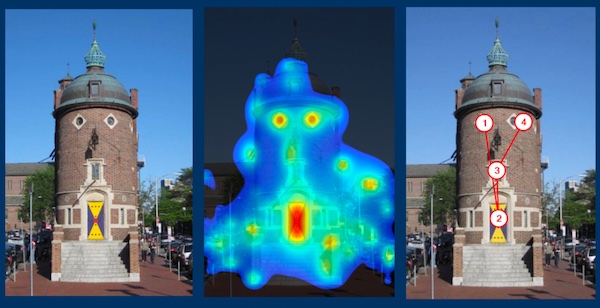

The Palladium, eye-tracked with iMotions software that creates heat maps that glow red where it detected that humans look most. The green areas show the statues that also draw people’s attention. Courtesy of The Human Architecture and Planning Institute, Inc.

In what now seem to be the antediluvian days of the ’70s, when I was a graduate student at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), my favorite courses were in Environmental Psychology and the Sociology of Design. Given changes in technologies, methodologies, environmental concerns, as well as economies of scale touching on all levels of urban politics and policies, these areas of focus seemed to shift the least over the past half century. What I learned then are the only things that I still currently apply in my urban design practice.

By the mid-’80s, these “softer” courses had been abolished from the GSD’s curriculum. Of course, we were told that the study of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design easily incorporated these ideas into more rigidly structured programing, which involved studios. Harvard’s GSD is generally ranked as the #1 design school in the world, so many others model their programs on what it does. This approach became de rigueur, worldwide. And that is unfortunate, because this loss in environmental design and designers has come at a very high cost.

However, over the recent decades a few thoughtful, if marginalized, voices have complained about this structured lack of human — and even humane — sensitivity regarding environmental design. One of these is the Human Architecture and Planning Institute (theHapi.org), an organization based in Concord, MA. In interestingly strategic ways, this group is going about a valuable task: trying to turn more conventional ways of teaching and practicing architecture and planning on their heads.

Founded by architect and educator Ann Sussman, HAPI’s mission “is to promote evidence-based design, using biometric and other tools to reveal hidden aspects of the human experience that direct our behavior in the built environment.” The intent is to draw on cognitive science and emerging methodologies, particularly biometric research, to understand how design actually impacts people. The goal is to use this research and its findings to create happier, more enriching, and healthier public and community experiences.

Biometric Heat Mapping of Harvard Lampoon building. Courtesy of The Human Architecture and Planning Institute, Inc.

The Institute is attempting to provide access to information, education, and research that increases our understanding of the psychological impact (on viewers) of how places are designed. This research involves using eye-tracking, heat-sensing, and other current biometric tools, and is being done in collaboration with research universities in different parts of the world. These investigations are at the intersection of science and the built environment; a number of the Institute’s studies attempt to comprehend in what ways modernist designs evoke more negative reactions than older, traditional ones. Sussman suggests that, at their most primeval, human beings were first animals seeking to sustain and defend themselves on the Savannah. Thus each environment triggers an immediate, instinctive visceral reaction. From studies, it appears that humans respond most positively to face-like facades.

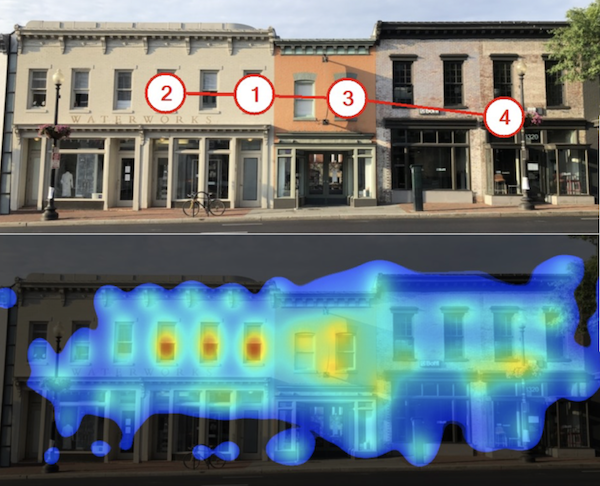

For example, using mobile and lab eye-tracking tools, HAPI’s Sensing Streetscape Study examines how people experience the streets of Amsterdam and Boston. Making use of researchers from Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, the study seeks to reveal how dense, newly developed residential areas provoke different experiences than those of the past.

One of the close-to-home studies, done in collaboration and with the support of Amsterdam University, compares the way individuals react to Boston’s Back Bay’s Newbury Street and nearby Boylston Street. Among the questions being asked: Why do we prefer one type of streetscape over another? What type of environment makes us happier and thus feel better? Through the application of heat mapping, the study reveals how stimuli, when they enter the human brain and body, direct our experience in subliminal ways.

A particularly exciting study was recently done in New York City. By incorporating tools provided by brain and cognitive science, researchers sought to understand how people perceive as well as experience the built environment. The findings are providing invaluable insights into plans involving urban design and architecture. The study monitored how various NYC facades implicitly attracted the eye without the viewer’s conscious awareness.

The study, which involved Tufts University, worked with 63 college students who were given a selection of photographs of New York City public buildings to look at. They all wore eye trackers as they viewed the images displayed on a monitor in front of them. Half of the visuals displayed the design characteristics of traditional neighborhood design. These included narrow streets, complex facades, and bilateral symmetry. The other images contained contemporary sights, mostly glass and steel high-rises. Subjects tended to show greater eye fixation on building fenestration in the older environments, as opposed to the nontraditional, larger-scale facades and structures.

The most provocative aspect of the HAPI’s approach is their “missing link” theory. The controversial argument is that modern architects were influenced by major traumas, such as World War I and child abuse, and the resulting PTSD shaped the ideas of the founding fathers of modern architecture, including such luminaries as Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, etc. Trauma changes the brain, runs the controversial claim, distorting survivor’s perception of “reality.” Survivors of abuse will design, unconsciously, in a manner shaped by their experience of the past.

Entrance to Gropius House in Lincoln, MA. Image is Courtesy of Historic New England.

To Ann Sussman, this theory explains why modern architecture looked so different from that of the past. It was a reflection of the horrors of WW I, with its gas attacks and terrible trench warfare. Why did modern architecture become so blank and faceless? For her, evidence is provided by looking at the Lincoln, MA, house built by a “founding father” of modern architecture, Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus. To her, his house, built in 1938, suggests a World War I bunker.

Building on this theory about the influence of PTSD, Sussman brings in her belief about the impact of autism and Asperger’s syndrome on modern architecture. She points out that most individuals relate positively to “faces” on facades and not to curtained or walled glass and metal structures. She suggests that many practitioners of modernist design suffered from either autism or some form of Asperger’s, which is why their architecture is so awkward to visually embrace.

These are challenging ideas, but modernism’s precursors began decades before WW I. The elegant austerity of Japanese design was introduced to the West after the middle of the 19th century. The American Shaker minimalist functional style was developing throughout that century as well. Hancock Shaker Village’s iconic spare Round Stone Barn (1826) is a spectacularly appealing circular structure. Late 19th-century English industrial design pioneer Christopher Dresser specialized in creating minimalist metal objects, practical as well as decorative. Some of Dresser’s metalwork designs are still in production and are now manufactured by Alessi.

Pioneering German architect/graphic designer/industrial designer Peter Behrens had a long career designing objects, typefaces, and important buildings in a range of styles from the turn-of-century to the 1930s. Several of the leading names to come in modernist architecture worked for his firm when they were starting out, including Mies, Le Corbusier, and Gropius.

Biometric Heat Study Image of “M” Street block in Washington, DC. Courtesy of The Human Architecture and Planning Institute, Inc.

Another transitional figure was Belgian architect/designer Victor Horta. He started out as founder of Art Nouveau in Belgium, but he is also considered a vital precursor of modern architecture. His later work moved away from the organic thrust of Art Nouveau to embrace more geometric and formal approaches. He made highly original use of open floor plans, steel frames, and skylights to bring light into structures.

Mixing Sussman’s provocative theories with the various other components — Wiener Werkstatte, Dutch De Stijl, Russian Constructivism, Prague Cubism, German New Objectivity, French and American Art Deco — will probably bring us closer to the actual underpinnings of modernist architecture.

Despite some of its questionable theoretical premises (at least regarding history), the cognitive architecture approach espoused by the Human Architecture and Planning Institute is applying a welcome new paradigm that responds in a fresh way to the built environment. Evolving biometric tools will no doubt lead to a better understanding of human behavior, which means professional practitioners can increasingly design more humane built environments. Now if only established schools of architecture and planning would start to seriously teach it.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program and, since 2002, he has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Writing about urbanism, architecture, design and fine arts, Mark is associate editor of Arts Fuse.

Thanks for your informative article.

It seems like there is an attempt to cement postmodern architecture in the US. There are some very good examples of postmodern architecture but postmodernism, as an anti-modernism stance, gave plenty of room to produce kish architecture and allowed for the mutation of very classic architectural components, with a direct impact on the streetscape.

The HAPi examples noted in the article are from Anglo cities and yet HAPi is presented as a new worldwide paradigm.

Modern architecture, and its precursors, thrived in many places. In Venezuela (my home country), particularly in Caracas, there are plenty of very good examples. I believe “modernism” succeeded there because the designs were primarily rooted in the local culture, its physical and natural context. The best example is perhaps the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas. Modernism in Venezuela took place during a time of economic growth and development. This might help having a positive perception about modernism.

Disregarding people design capabilities because of their own personal experiences it would simply make the architecture and planning profession even more exclusive. Ann Sussman seems to suggest that kids escaping from a war devasted country or other tragic circumstances should never lead the design profession; unless, I guess, they subscribe to her American postmodern design approach and face-like facades.

How good would it be if only designers will have access to biometric tools? or would we have planning board hearings where attendees can ware eye trackers to review a given project? If so, zoning dimensional requirements should be eliminated.

I think we will all be seeing and perceiving design very differently.