Author Interview: Linda Hirshman on the Battle Against Human Bondage

By Blake Maddux

“I always wanted to write about abolition, because abolition is the most successful social movement in American history.”

In the Author’s Note to her new book, Linda Hirshman explains why she writes about social movements — they are “moments when people act collectively to change their shared world.”

In the Author’s Note to her new book, Linda Hirshman explains why she writes about social movements — they are “moments when people act collectively to change their shared world.”

Since 2012, Hirshman has published volumes about the struggle for gay equality, the influence of Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg (click here for my Arts Fuse interview about that book), and the decades-long fight against sexual abuse and harassment.

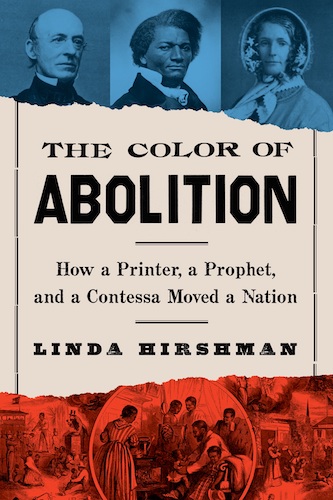

In the recently published The Color of Abolition: How a Printer, a Prophet, and a Contessa Moved a Nation (HarperCollins/Mariner Books), Hirshman turns away from the present and homes in on antebellum Massachusetts (primarily) to focus on abolition. No social movement in American history, she argues, matters more.

She tells the story of the battle against human bondage via the contributions of publisher William Lloyd Garrison, escaped slave, writer, and lecturer Frederick Douglass, and socialite Maria Weston Chapman.

The last of these three subjects will be a revelation to most if not all readers. While the primary and secondary literature on Garrison and Douglass is extensive and well known, that on Weston Chapman is either exiguous or not widely read (or both).

As noble as their collective goal was, the “printer,” the “prophet,” and the “contessa,” each had their own individual motives and motivations.

Thus, Hirshman argues in the introduction, “As with all alliances, sooner or later the question would arise: Who gets what from the deal? This is what breaks up all alliances, however fruitful the collaboration. By 1853, the partnership … was done. The creation, duration, and impact of their alliance to abolish slavery is the subject of this book.”

The trained lawyer (JD, University of Chicago) and philosopher (PhD, University of Illinois-Chicago) spoke to the Arts Fuse by phone ahead of her speaking engagements in conjunction with Boston Athenaeum on February 23 and the New England Historic Genealogical Society on February 28.

The Arts Fuse: Your previous books are about recent events and contemporary issues. What transported you back to antebellum America for The Color of Abolition?

Linda Hirshman: I always wanted to write about abolition, because abolition is the most successful social movement in American history.

I think it’s fair to date the start of the modern, immediatist, interracial antislavery movement — which ultimately culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation — from 1831, when the first issue of the Liberator was published. So it’s only 34 years, which is, against an injustice so dug-in, and so lucrative, and so resistant, really an amazing accomplishment.

AF: Why did you decide to structure the book around these three major figures of the abolitionist movement?

LH: I was looking for some characters who would allow me to have an entrée to write about the abolitionist movement. When I learned that William Lloyd Garrison’s printing operation in Boston had actually produced the physical copies of Frederick Douglass’s great first memoir, I thought, “Oh, that relationship looks interesting,” particularly because it was interracial.

As I was working, I discovered Maria Weston Chapman. I realized that there was almost nothing about her in the literature, so she was overlooked, which we writers just love! And the Boston Public Library had a treasure trove of letters in the Weston collection. They have hundreds of letters. She was a great letter writer and people wrote to her because she was really running the show. She and her sisters wrote to each other and people wrote to her sisters. So there was a shitload of original material that hadn’t been given anything like the attention it deserved.

Her role was radically underreported. She really mattered to the movement’s success and to its breakup.

AF: What percentage of American high school graduates do you think have heard of Maria Weston Chapman?

LH: I would say a smaller percentage than vaxxed and boosted people who have died of COVID. A tiny number. But they’re going to learn about her from me! I hope someone will buy it and make a movie. It’s a wonderful, romantic story.

AF: What do you think accounts for her — for lack of a better word — obscurity?

LH: She was not a speaker. The abolitionist movement used the spoken word a lot. They had a lecture corps that they sent all around.

That may account for part of it, but I believe that another reason is that people don’t look for women, and so they don’t find them. I can’t think of any other explanation for it.

She wrote a lot. She had a very important newsletter, Right and Wrong in Boston, from the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. She wrote poetry and she wrote hymns and she gathered together a very important book of antislavery writings called The Liberty Bell every year. So it wasn’t like she was some shrinking violet.

AF: How does bringing her into the picture teach readers more about Douglass and Garrison, whom far more people know about?

Linda Hirshman. Photo: Nina Subin

LH: The letters to and from Maria Weston Chapman tell a very vivid and graphic story of the lives of both Douglass and Garrison in the abolition movement. Her letters — and her sisters’ letters and the letters amongst her clique — reveal a great deal about what they were doing and their attitudes toward one another.

Second, her story illuminates the other characters who also reflected this. She was very tight with Edmund Quincy of the Massachusetts family that included mayors of Boston and a president of Harvard. Their letters to and from each other reveal the attitudes and role of the Boston Brahmins in the antislavery movement.

They also reveal the condescension toward both Garrison and Douglass, but especially the racist condescension toward Douglass. It’s very hard to imagine anybody being condescending toward Frederick Douglass, who is arguably the most important American of the 19th century, and maybe ever.

Maria Weston Chapman was both a great contributor to the movement and a living manifestation of the layer of racism that even the best-intentioned white people can’t seem to get away from.

AF: Was the relationship among Douglass, Garrison, and Weston Chapman particularly strong or was it just one of convenience in the interest of advancing their mutual cause?

LH: Garrison and Maria Weston Chapman were very, very, very close. Her townhouse in Boston was the site of all the abolitionist get-togethers. Garrison was in that house all the time.

She worshiped and was faithful to him and his positions — even as they became increasingly out of step with what was needed — to the end. When she left for Europe in 1848, Garrison wrote in a letter that he could not imagine how they would get along with her gone. She meant the world to him and the movement.

Garrison and Douglass, we do not see a warm relationship between them, but they were allies. They traveled together a lot. They went on speaking tours together, and these were dangerous undertakings. Douglass was sometimes not able to sit in the same train car or get anything to eat.

They wrote about each other warmly in terms of their effectiveness, and what great speakers they were, and how important their thinking was, and how successful their organizing was.

I think the best way to understand how Garrison felt about Douglass is when Douglass’s British friends raised a fund to buy his freedom. Garrison normally believed in no ransom for slaveholders. He was opposed to buying freedom. But he defended Douglass’s decision to do so and made completely inconsistent arguments in favor of his doing so. He even contributed to the fund!

You don’t see such warm sentiments expressed from Douglass to Garrison, even before the breach. But we know that Douglass was capable of expressing his gratitude to his white allies. There are letters to other people in the movement that are quite warm and personal.

AF: In the end, were Garrison and Weston Chapman simply unable to view Douglass as an equal (and potentially a superior)?

Maria Weston Chapman. Photo: Wiki Common

LH: You do get that feeling, yes. More with Weston Chapman than with Garrison. Douglass did something that Garrison could not forgive, which was that he abandoned the Garrisonian opposition to politics. Garrison thought that the Constitution was a bargain with the devil and a proslavery document. And he was probably right.

When Douglass went over to the political branch of abolition, Garrison treated him worse than he treated many white men who had embraced the political road.

So you have to think that it must have been, at some level, impossible for them to realize that he was not just their equal. He was their superior.

It is still shocking to see the language that they used about Douglass coming from abolitionists. And it isn’t like people didn’t know that you weren’t supposed to talk like that. Both Garrison and Douglass in their own letters said quite clearly that that word [you know the one she means] was toxic.

AF: Was Boston fairly enlightened on racial issues during this time and was Massachusetts ahead of other states in terms of its advocacy of abolition?

LH: Massachusetts was one the earliest states to abolish slavery after the American Revolution. But a lot of Massachusetts’s reputation comes from the state, not the city of Boston. Boston was one of the more racist places in emancipated Massachusetts. This was because Boston was a mercantile city that was dependent on the profits of the slave trade, as was New York. A lot of the abolitionist sentiment in Massachusetts came from small towns, like Lynn and New Bedford.

(Read Hirshman’s latest column for the Atlantic – “The Fight for Democracy Will Be a Long, Long Haul” – here.)

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and one-year-old twins—Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson—in Salem, MA.