Book Review: Samuel R. Delany’s “Dhalgren” — A Critical War of Words

By Vincent Czyz

The jury’s in. The critics who agreed with an early assessment that 1975’s Dhalgren is a “literary landmark” get to touch champagne flutes and congratulate one another.

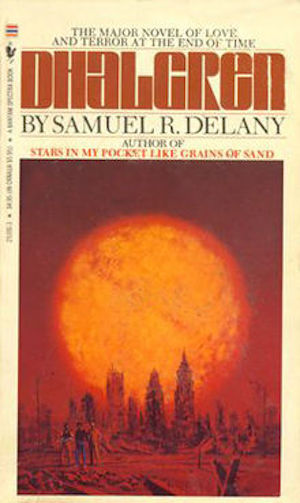

On Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren. Edited by Bill Wood. Wilder Publications, 272 pages, $31.99 hardback, $21.99, paperback.

“Very few suspect the existence of this city. It is as if not only the media but the laws of perspective themselves have redesigned knowledge and perception to pass it by. Rumor says there is practically no power here. Neither television cameras nor on-the-spot broadcasts function: that such a catastrophe as this should be opaque, and therefore dull, to the electric nation! It is a city of inner discordances and retinal distortions.” – Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren

“Very few suspect the existence of this city. It is as if not only the media but the laws of perspective themselves have redesigned knowledge and perception to pass it by. Rumor says there is practically no power here. Neither television cameras nor on-the-spot broadcasts function: that such a catastrophe as this should be opaque, and therefore dull, to the electric nation! It is a city of inner discordances and retinal distortions.” – Samuel R. Delany, Dhalgren

“Dhalgren is a tragic failure,” howled science fiction heavyweight Harlan Ellison in his February 1975 review for the Los Angeles Times. “An unrelenting bore of a literary exercise afflicted with elephantiasis, anemia of ideas, and malnutrition of plot.”

“I have just read the very best ever to come out of the science fiction field,” countered Theodore Sturgeon, another SF heavyweight who, in my opinion, was a tad heavier. “Having experienced it, you will stand taller, understand more, and press your horizons back a little further away than you ever knew they could go.” His rave in Galaxy Magazine began circulating less than a month after Ellison’s screed hit the press.

Critic Darrell Schweitzer, writing for the fanzine Outworlds (October 1975), threw in with Ellison, calling Dhalgren “shockingly bad.” “It is a dreary, dead book,” he went on to say, “about as devoid of content as any piece of writing can be and still have the words arranged in any coherent order.”

That seems a pretty definitive judgment, and yet 45 years later Schweitzer repented: “I have to admit that Dhalgren seems well on its way to fulfilling the definition of ‘great literature’ I give here, i.e., that it means something different to readers at different points in their lives, and they keep coming back to it.”

Dhalgren first appeared as an 879-page paperback science fiction novel from Bantam Books in January 1975. It went through 19 printings before Bantam let it go out of print. Two hardback editions and a paperback, this one from Weslyan University Press, followed before Vintage Books reissued the mammoth novel in 2001. It remains in print and is still being read, written about, and referenced (Junot Diaz even gives it a shout-out in one of his short stories). In other words, the jury’s in, and the critics who agreed with Sturgeon’s assessment that Dhalgren is a “literary landmark” get to touch champagne flutes and congratulate one another.

The battles in this critical war of words, among other things, have now been collected in On Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, edited by Bill Wood. Wood has amassed more than 200 pages of reviews, commentary, and critical essays on Delany’s polarizing magnum opus. While many are contemporaneous with Dhalgren’s first incarnation, the preponderance of these pages were written decades later. A discussion of Delany’s novel Hogg, which lacks Dhalgren’s popularity but is strangely — and perhaps darkly — connected to it, closes out the collection.

The battles in this critical war of words, among other things, have now been collected in On Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren, edited by Bill Wood. Wood has amassed more than 200 pages of reviews, commentary, and critical essays on Delany’s polarizing magnum opus. While many are contemporaneous with Dhalgren’s first incarnation, the preponderance of these pages were written decades later. A discussion of Delany’s novel Hogg, which lacks Dhalgren’s popularity but is strangely — and perhaps darkly — connected to it, closes out the collection.

A handsome volume whose cover is an elegantly rendered apocalyptic cityscape (presided over by two out-of-phase moons), the book leads off with a review by Steven Paley. Despite the fact that he was writing for a college newspaper (in Wisconsin), Paley delivers an inspired disquisition on Dhalgren. What’s truly delightful is that the review is a “reproduction” of the Bellona Times, the fictional newspaper circulating in Delany’s fictional city. The headline of Paley’s piece, Only One Hundred Years Till Death of Harlow!, reflects the Bellona Times’s flagrant disregard for calendrical accuracy. It’s even written from the perspective and in the voice of Roger Calkins, the publisher of the Bellona Times.

Next up is Gerald Jonas, who, writing for the New York Times, does an admirable job of summing up the novel’s action: “An unexplained disaster has destroyed Bellona’s normal social fabric, and done something irreparable to the space-time continuum itself [recall the two out-of-phase moons]. Most of the inhabitants have fled; the few who remain and those who arrive by choice have coalesced into a new kind of community, an unstable mixture of civility and anarchy. The hero … has forgotten his name; he is known variously as Kidd, kid, and the Kid.… More or less by accident, he becomes poet laureate of Bellona; he also assumes the leadership of a young gang loosely modeled on the Hell’s Angels … has numerous encounters with a large cast of characters … and … records many of his reactions in a battered notebook, which may or may not be the original manuscript of the vast creation entitled [sic] ‘Dhalgren.’”

Jonas’s Dhalgren-friendly review for the Times was followed about a year later by another for Penthouse, which, though still a ringing endorsement, shifts tone and focus.

The heart of this collection, however, isn’t the reviews; it’s the critical analyses. And the critic who does the most to unravel Dhalgren’s engimas, of which there are not a few, is K. Leslie Steiner, a.k.a. Samuel R. Delany. As Wood explains, Steiner is a literary joke inspired by the 18th-century English poet Alexander Pope, who “invented a critical alter-ego” he called Barnivelt, a name Pope attached to several essays he penned about his own poetry.

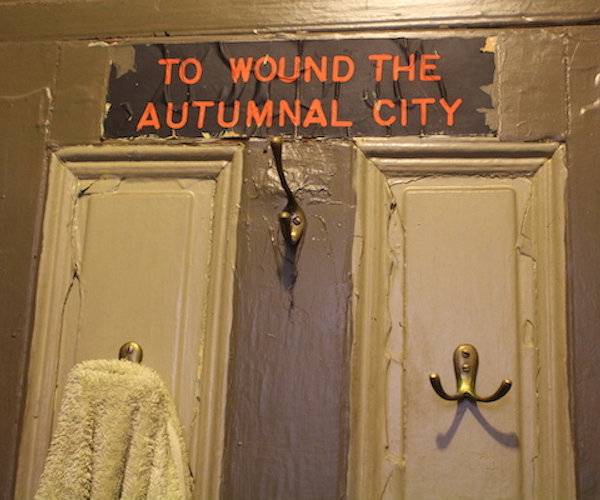

The bathroom door in Samuel Delany’s apartment, which he inhabited for some 42 years before relocating to Philadelphia. Photo: courtesy of the artist

While the observation that Dhalgren descends like a spelunker into the nature of reality is reiterated often enough to be a motif among the novel’s more astute critics, Steiner’s “Some Remarks Toward a Reading of Dhalgren” goes much further, painstakingly illuminating Dhalgren’s take on reality as well as its affinity for verbal illusions. It’s a virtuoso performance that brings Victor Hugo into an examination of the “interplay between perspective, perception, distortion, and architecture”; clues us in as to why all Kid recalls from a truck ride is the word artichokes; touches on Viktor Shklovsky’s definition of art as a form of defamiliarization — a concept eminently applicable to Bellona; and, among many other things, alerts us, in the event we didn’t notice, that Dhalgren contains pastiches of W.H. Auden, Rainier Maria Rilke, and Paul Valery.

Steiner isn’t the whole critical show, however. There are outstanding essays by Robert Elliot Fox, Marc Gawron, and Delany scholar Ken James, who compiled In Search of Silence, the first volume of Delany’s journals.

Samuel R.Delany in 2018. Photo: Wiki Common

By now it should be clear that On Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren is a book for fans of Delany’s most controversial novel. It may be less clear that I’m one such fan. I read it three times, getting more out of the experience with each pass (no doubt another mark of great literature). The third time through, for example, I suddenly recognized Kid as another Ahab, Bellona as his whale, and Bellona’s sky — obliterated by clouds and smoke, blanked by gray — as the whiteness of the whale. Paragraphs like the following seemed to support my intuition: “There is no articulate resonance. The common problem, I suppose, is to have more to say than vocabulary and syntax can bear. That is why I am hunting in these desiccated streets. The smoke hides the sky’s variety, stains consciousness, covers the holocaust with something safe and insubstantial. It protects from greater flame.”

Kid, I decided, hunts not with a harpoon but with a pen, with poetry. And what he’s chasing isn’t a leviathan but meaning itself. In a sense that’s really what Ahab is after (recall his speech about all visible things being but a pasteboard mask to be punched through). There’s also the name Bellona, which belonged to a Roman goddess of war before Delany bestowed it on his time-twisting, space-distorting city, but it’s awfully close to ballena, the zoological name for a whale.

What’s more, seven years before completing Dhalgren, Delany had already published a space opera called Nova, an overt retelling of Moby-Dick: “The whole continuum in the area of a nova is space that has been twisted away,” says Lorque von Ray, Ahab’s futuristic counterpart. “We have to go to the rim of chaos and bring back a handful of fire…. Where we’re going all law has broken down.” It’s hard not to see parallels between this disintegrating star, which is von Ray’s white whale, and Bellona, a city whose defining aspect is the overthrow of order — be it social, legal, or natural.

Here, at the conclusion, let us go back to the beginning. The novel commences in mid-sentence: “—to wound the autumnal city. So howled out for the world to give him a name.” Dhalgren ends with another fragment: “I have come to—.” As at least two critics point out, the sentences link up but not quite: there’s the repeated “to.” A kind of stutter or perhaps an overlap. In either case the duplication is deliberate (as is pretty much everything in this novel), and in either case the conjoined ending and beginning invite the reader to return. After reading this compilation of critical commentary, I have no doubt I will — if for no other reason than to finish tracking down the sources of those Melvillian echoes haunting Bellona’s deserted streets.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Czyz misses (as I did) what is actually happening in the Joycean recirculation trope:

When I met Chip decades ago, he gently noted another reading. Kid is unconscious in this broken city of mirrors, but at the end “comes to” and accepts his task of wounding the autumnal city.

I suggest you read On Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren. You might also consider some of his essay collections. In an interview reprinted in one of those collections, Delany admits he had not read Finnegans Wake as of 1975, when Dhalgren was published, and was not alluding to Joyce or borrowing a Joycean technique or even aware of the conjoined ending and beginning of Wake. More to the point, in his essay “Some Remarks toward a Reading of Dhalgren,” under the Steiner penname, he specifically and somewhat acidly discounts comparisons to Joyce, ending a long paragraph with: “the technique [in the last chapter of Dhalgren] has no parallel in either the Portrait [of an Artist as a Young Man], Ulysses, or the Wake.” Steiner/Delany analyzes at length what was going on, and I think you would find it worthwhile reading. It is not recirculation (Joyce, BTW, borrowed the trope from G. Vico & his interpretation of history). It is, to my mind, more interesting than recirculation. That said, I left out dozens and dozens of tropes in my discussion of this collection of reviews and critical analyses of Dhalgren. To explain what Delany was actually doing with the conjoined ending and beginning, at least if Delany himself is to be believed–and he makes a very persuasive case, would have taken up twice the wordcount of the actual review. At least.

A typo–the fanzine Schweitzer initially reviewed the novel for was OUTWORLDS…plural.

https://fanac.org/fanzines/Outworlds/ The 10/75 issue and others can be read here.

Thanks for that, Todd. It’s incorrect in the book itself as well. I sent an email to the publisher.

VCzyz

You got the line of the novel quite wrong. Considering its import, the fact that you’ve read it three times, and how much you claim to like it, it kind of undermines you.

Which line?

Not sure why people take such glee in leaving nitpicky remarks in the comment section.

I just wanted to say thank you for the thoughtful overview / review. I’m writing about Dhalgren for my dissertation but it still often seems elusive. It’s a pleasure to find other people still chewing on it as well.

This book is completely incomprehensible, and those claiming they ‘understand’ it are lying through their teeth.

I read the book shortly after it was published. It was an uncomfortable time for the world in general and a haunted time in my life. I was studying Physics at university while living in the back of my pickup truck. I wanted something to read that would mean a bit more than the maelstrom of contradictory nonsense in which I found myself. I chose the wrong book.

I read the entire book, convincing myself that on the next page it would all be brought together and make sense.

Once again I had to learn to live with disappointment.

I had the pleasure of bringing Delaney to BU a decade ago for a documentary about him. A memorable evening including dinner after, and my worry with his order that this aging overweight man is eating far more fatty pork than he should. I guess I was wrong: gloriously, he’s still about.

Great review of reviews of an epic zen mind bender – a book I’ve endlessly lost myself in -the ultimate trapped on a desert island or 12 hr flight anywhere book…

The only fiction that can double as a semesters course work in Psych, Sociology & English Courses

Thanks for the review and this comment section.

I have been working on Dahlgren for the better part of a year, going back and refreshing — but it’s impossible for me to sit for hours and read straight through.

I find it hard to believe that Delany hadn’t read Finnegan’s Wake or Ulysses or Moby Dick — they are so much a part of the collective unconscious. Maybe that is just the way some people think?

Dahlgren may be best experienced as an audio book. The images swim around in my head much better when they come through my ears than lifted off the printed page with my eyes.