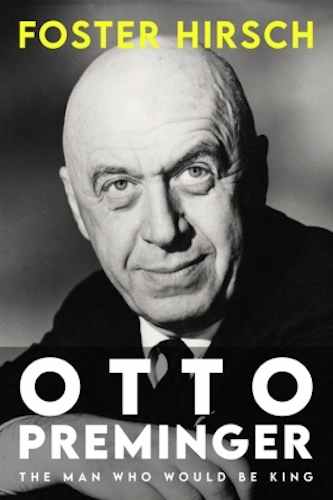

Film Interview: Foster Hirsch on “Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King”

By David Stewart

“I’m hoping people will revisit Otto Preminger’s movies because he made some of the best films ever made in America.”

During one of Hollywood’s Golden Eras, from 1946 to 1960, Otto Preminger was among the industry’s most successful directors and producers. Like his contemporaries Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder, Preminger fled Europe during the rise of the Third Reich. His theatrical background working under Max Reinhardt helped launch his career directing plays on Broadway and then films in Hollywood. His versatility stood him well in the studio system: he made noirs (Laura, The Man with the Golden Arm), courtroom dramas (Anatomy of a Murder, Advise and Consent), and big-budget epics (Exodus). Preminger delivered a succession of hit films before the studios diverted their attention to the new wave of up-and-coming filmmakers like Mike Nichols (another wartime expat), Peter Bogdanovich, and Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider being his psychedelic Citizen Kane).

During one of Hollywood’s Golden Eras, from 1946 to 1960, Otto Preminger was among the industry’s most successful directors and producers. Like his contemporaries Ernst Lubitsch and Billy Wilder, Preminger fled Europe during the rise of the Third Reich. His theatrical background working under Max Reinhardt helped launch his career directing plays on Broadway and then films in Hollywood. His versatility stood him well in the studio system: he made noirs (Laura, The Man with the Golden Arm), courtroom dramas (Anatomy of a Murder, Advise and Consent), and big-budget epics (Exodus). Preminger delivered a succession of hit films before the studios diverted their attention to the new wave of up-and-coming filmmakers like Mike Nichols (another wartime expat), Peter Bogdanovich, and Dennis Hopper (Easy Rider being his psychedelic Citizen Kane).

Film historian Foster Hirsch revisits the life and work of this complicated director/producer in the fourth edition of Otto Preminger: The Man Who Would Be King (University of Kentucky Press, 592 pages, $34.95). Preminger’s name may not be as recognizable to moviegoers as that of Stanley Kubrick or Martin Scorsese, but Hirsch makes the case that his output as a filmmaker and stage director is as expansive and as accomplished. Beyond his films, Preminger’s reputation on set as a screaming tyrant of a director led to Hollywood dubbing him “Otto the Terrible.” Jean Seberg’s baptism by fire — moving from Midwestern beauty queen to Otto’s leading lady in his commercially panned Saint Joan — was the subject of gossipy speculation long before the troubled actress took her own life in 1979. Even Robert Mitchum felt Preminger’s wrath and reacted accordingly: he slapped the director after Preminger told the actor to slap his Angel Face costar, Jean Simmons, as hard as he could. Then, there’s Preminger’s brief, yet memorable, on-screen performance as the nasty Colonel Klink-ish commandant of a POW camp in Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17. Hirsch speculates that this performance might well give us a sense of “Otto on a good day.” The book walks a tightrope between hagiography and warts-and-all expose. Hirsch is protective of Preminger’s stature as an artist, defending misfires (like Skidoo), and insisting that the director’s disparaged 1959 version of the opera Porgy and Bess be reevaluated.

I spoke with the film historian and Brooklyn College film instructor from his home in Manhattan.

The Arts Fuse: What made you want to revisit Preminger’s life and career after 14 years?

Foster Hirsch: Normally, when I’m done with a project, I would like to move on. Then, I realized that I had been thinking about Preminger’s films. I’ve been the host of very rare screenings of Porgy and Bess. The only time it’s been shown is when I’ve pushed to have it shown. It’s a lost film; it probably will never be seen again. I was thinking about the film and the intense feelings that it arouses. It made me realize that Otto was ahead of his time in so many ways: he would bring a very sophisticated response to subjects that other filmmakers would not touch. His films are more complex and thought-provoking than you might think. They’re about subjects that continue to matter.

Otto Preminger working with Billy Strayhorn and Duke Ellington on the score for Anatomy of a Murder.

AF: For someone who had a challenging personality on set and when dealing with the studios, I was surprised that Otto liked to engage with audiences after his screenings.

Hirsch: Otto liked to have discussions with the audience! I remember seeing Anatomy of a Murder when it opened at the Warner Theater in Beverly Hills; a fabulous film. After one of the screenings, there was Preminger, standing in the lobby of the theater and asking us, ‘What did you think of the jury’s verdict?’ He wanted to discuss it with us. The film was an attack on complacency. Otto loved America; he was proud to be a citizen and he loved our system of trial by jury. It is an imperfect system, but he loved it. When Otto showed the film in Russia, the audience came up and said, “Why bother to have a trial? The man is obviously guilty, so execute him.” Otto said, “That’s not how we do it in America.” If he were alive now and a young film student wrote to him asking to come to the office for an interview, he would say yes. He was open to everybody. It was within his character to plant himself in the lobby of a theater and engage with the audience. At the same time, he was an imperious, tyrannical, difficult man.

AF: What was the root cause to Otto’s temperament?

Hirsch: As with so much with Otto, the answer calls for a number of explanations. Having talked to his family, especially his brother Ingo, I think there may have been something wrong with him. His temper could have been a result of some kind of chemical imbalance that they hadn’t quite studied at the time. Ingo made a point of saying that nobody else in the family acted that way. He was embarrassed by Otto’s legendary tantrums. Preminger could turn against anyone, including his wife. He couldn’t control the anger; some people said he used his fury deliberately, as a way to get what he wanted from a recalcitrant actor. That may have been true, but the truth is that he was a man with an ungovernable temper. He was also a man born to great wealth. He came from a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna, his father was a prominent lawyer for the government. They had to leave when the Nazis took over. So there’s the volatile mix: something is off in his system chemically, the privileged family background, and the temperament of a man who loved to take charge. The result — someone who is very hard to work with.

AF: Preminger’s presence in film lore revolves around the image of the tyrannical bully who treated his successful, yet troubled actresses (Gene Tierney and Jean Seberg) badly. Is that charge accurate?

Hirsch: I’m not sure the mystery of Otto can be so neatly explained. He was a man of contradictions; he’d yell and scream, yet he would help people who needed help. Tierney had struggles with mental illness when she was cast in Advise and Consent — years after she played Laura in Preminger’s eponymous film. People said that, while on the set, Otto couldn’t have been more caring and nurturing to her.

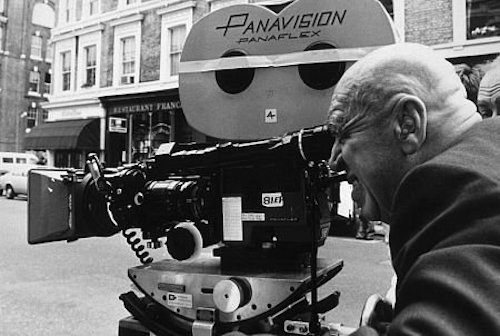

Otto Preminger checking a camera shot.

AF: Otto’s approach to filmmaking, which was emotionally detached, may feel dated to some. He favored long takes and few edits. But his explorations of aspects of America, such as our political system in Advise and Consent, remain vital.

Hirsch: Advise and Consent is one of the best films ever made about the American political system. Everybody who cares about our politics and political system needs to see this movie. Its conclusions are not obvious or simple, but he shows you a world in which both sides of the aisle work together for the common good, just like today. (Laughter) Otto thought our system of checks and balances was a magnificent system — he was a lawyer before becoming a filmmaker. He thought that our system, imperfect as it is, was the best that had ever been devised. His films about America are complex because there is no simple designation of guilt or innocence.

AF: Do you think today’s audiences will be able to appreciate 1959’s Porgy and Bess?

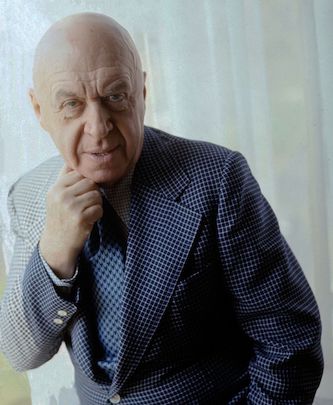

Otto Preminger. Photo: Allan Warren/Wiki Common

Hirsch: The Preminger family has no rights to the film; they’re all for making it available. But the movie has been entangled in legal and rights issues for decades. Samuel Goldwyn, who produced the film, took out rights for the film only for 14 years after it was released. After that time, it became a matter of the rights holders (the Gershwin estate, DuBose Hayward’s estate). The problem is that the estates of the creators of Porgy and Bess have been at odds with each other and Samuel Goldwyn’s company is also at odds. Apparently, Ira Gershwin didn’t like the film. But so what? In effect, the movie has been suppressed, and it’s also been accused of being racist. How can you charge that this film is racist? There are productions of Porgy and Bess on opera stages all over the world. Why are stagings of Porgy and Bess opera presented without protest, but Otto’s film is tarred with the brush of being a racist depiction? I don’t get it. There are only a few copies in the world. They’re in the hands of private collectors. The Library of Congress has a copy, but it isn’t available for screening. Apparently, the Samuel Goldwyn company has no copy.

AF: Preminger’s contribution to ending the Hollywood Blacklist undercuts the myth that Kirk Douglas did it when he destigmatized Dalton Trumbo by giving him screen credit for writing Spartacus.

Hirsch: When Preminger gave Trumbo screen credit for having written Exodus, that was the official end of the Blacklist. Otto announced that Trumbo was the screenwriter of Exodus in January 1960. He said, “I don’t care about his politics, he’s a good writer who’s written a good screenplay who deserves screen credit for his work.” Nine months later, Douglas announced Trumbo was the screenwriter of Spartacus. For the rest of his life, Douglas took credit for breaking the Blacklist. Not true: Preminger broke the Blacklist. Douglas certainly did the right thing by publicly crediting Trumbo, but it was nine months after Otto had announced it.

AF: What do you hope readers will take away from this edition of The Man Who Would Be King?

Hirsch: I’m hoping people will revisit the movies because Preminger made some of the best films ever made in America. They aren’t dated. They remain thoughtful and thought-provoking. I hope younger viewers will see them with a fresh and fair eye. They’re not hip in the sense that there is no staccato editing. Otto thought every cut was an interruption, whereas today’s directors use rapid editing to excite the audience. I tell my students, “Let’s ban editing in movies for the next 10 years and have long takes.” Today’s cinematography is all close-up, close-up, close-up. When you give audiences long-shots, as in Porgy and Bess, there’s so much to take in and more responsibility for the audience to invest in the viewing experience.

David Stewart is a professor of Film and Media Studies at Plymouth State University. Along with teaching, he is a documentary researcher and contributing writer for the Film Stage and PleaseKillMe.com. His film credits include Amy Scott’s documentary Hal and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl. He lives outside of Boston with his family and beloved Fender acoustic, Nadine.

I worked with OP (as I, and a few others used to call him) on a truly awful film called Rosebud; he was indeed tyrannical, but I discovered early on in the shoot that if you dared to stand up to him — people were fired right left and centre, so there wasn’t much to lose except the job, and that wasn’t worth keeping if you were going to be got at — he admired and appreciated it. I managed that on day one of shooting when he roared at me for not pouring wine fast enough at a dinner party scene and I told him to get a wine waiter if he wanted it done professionally, and stormed off the set; a few minutes later there was a knock on my dressing room door and he came to apologize. We were friends thereafter (this was in, I think 1971) until his death, and met every time he came to London where I lived. When one of the editors was in Israel as his wife went into labour with their first child, back in the UK, Otto said ‘go, you must be there, not here, here’s your airfare”. He could be immensely generous, as you say.