Culture Vulture: Coming Attractions — Gloucester City Hall Murals

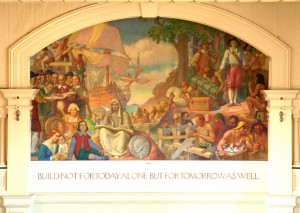

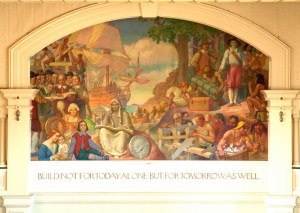

The Founding of Gloucester, as depicted on the wall murals at Gloucester City Hall.

Of the 100 or so events scheduled for Essex County’s Eighth Annual Trails and Sails Festival the last weekend of September, culture vultures should not miss Gloucester’s Committee for the Arts tours of Gloucester City Hall’s wall murals, created by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930’s. Culture Vulture talked about them with Susan Erony, the Gloucester artist and curator who will be leading the tours on September 26th and 27th.

CV: Given the resemblance of our current economic problems to the Great Depression, many of us have a new interest in the WPA and public art. Tell us what’s in Gloucester’s City Hall and how it got there.

Gloucester artist and curator Susan Erony

SE: Gloucester has a remarkable collection of WPA and other New Deal program murals that were painted between 1934 and 1942. American artists had been coming to Gloucester regularly since about the 1880s, after Fitz Henry Lane, Winslow Homer, William Morris Hunt planted the seeds of an art colony. By the 1930s, artists of the stature of John Sloan, Stuart Davis, Milton Avery, Marsden Hartley, and Edward Hopper made Gloucester one of the most important places in this country for the development of American art.

CV: Is their work among the murals in Gloucester City Hall?

SE: Unfortunately, no. Most of the murals are by Charles Allen Winter, who grew up in the Midwest, studied in Paris and Rome, and began to summer in Gloucester with his wife, Alice Beach Winter, also a painter, in 1914. They became full time residents in 1931.

CV: Was there something about Winter that predisposed him to public art or was he in desperate need of money?

SE: Both Winter and his wife were political people. Alice was a suffragette who in 1912, had joined with John Sloan, Stuart Davis, and others to start the socialist magazine “The Masses,” and became its art editor. Charles was the political cartoonist for the “Pittsburgh Post” and illustrator for “Colliers Weekly,” Hearst and other magazines. So when FDR proposed his New Deal for the American people – which came to include the WPA — the Winters were ready.

CV: Tell us how the WPA got involved with visual artists.

SE: In 1933, George Biddle, who was himself a painter, friend and former classmate of Franklin Roosevelt, saw the Depression destroying the arts community. He appealed to F.D.R. to create work specifically for artists, rather than putting them to work as general laborers. His ideas were based on a prototype of the Mexican government, which paid artists to work at plasterers’ wages “in order to express on the walls of the government buildings the social idea of the Mexican revolution.” Biddle’s appeal led to the establishment, in 1933 and 1934, of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), to provide public service jobs during the bitter winter of 1933-34.

CV: Who chose the art and what was its stated objective?

SE: Its stated goal and the goal of its successor program, the Treasury Department’s Section of Painting and Sculpture, was to collect “masterpieces” for the government. There was an advisory committee of established and respected American painters – including Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, Rockwell Kent, and Reginald Marsh — that was antagonistic to European modernism. PWAP lasted less than one year, but it provided employment for approximately 3,700 artists who created nearly 15,000 works of art – including one of the murals in Gloucester’s City Hall.

CV: So there were in fact at least two separate New Deal projects for artists?

SE: In August of 1935, another project, the Federal Art Project (FAP) was established by the WPA that continued until 1943, when World War II redirected all priorities and economic recovery was on its way. Thus ended the first major era of government patronage for art in the United States.

CV: How would you describe that era for artists?

SE: Many New Deal Administrators, including WPA Director Harry Hopkins and FAP Director Holger Cahill, believed that art could and should be a part of the daily lives of all Americans, not just the elite. So artists were both legitimized in a new way and reached a larger audience. Millions of Americans experienced concerts and plays for the first time, as well as original professional paintings and drawings – almost always for free. Thousands of children were offered free art and music classes, which attracted adults as well. Artists were enlisted to help bring together peoples of different ethnic, demographic and racial groups into a common task, to serve as catalysts for regional community and democratic activity – a commons for the people.

By 1940, there were 84 community art entries with an average monthly participation of 350,000 people. The FAP reframed artistic work as productive labor whose client was the American people. One of their early press releases read: WPA artists are interpreting America to Americans.

CV: It seems to me that while most of the artists would have welcomed the income, not all artists would have been enthusiastic about such democratization of the arts. How did the artistic community, in fact, respond?

SE: The WPA was not universally well-regarded by visual artists. Art and democracy do not necessarily sit easily with each other. Art works are by traditional definition unique and special. Artists are outsiders, not like most people. But democracy implies equality and popular will. So those who came to see their work as democratic included commercial, product, window, and trade show designers, American Scene painters, abstractionists and realists. Communists and Madison Avenue pr people were all suddenly part of a democratic culture.

What is wondrous is that during this period, the meanings of both democracy and art were debated at length by everyone from housewives to religious leaders to academics and government workers. The arts programs marked the Federal Government’s first acknowledgment of the significance of the arts in American life and encouraged a communal spirit among artists. But it’s surprising how many kinds of artists worked under the Federal Art Project. They included Arshile Gorky, Thomas Hart Benton, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, and Willem de Kooning.

CV: Am I wrong to think that none of these painters you mention actually created murals?

SE: Some of them did murals as well as easel art. But the arts programs were constantly under attack as boondoggles and public murals were the easiest form to sell to the public as having public worth. The Treasury Dept. was in charge of post offices and all federal buildings, the WPA had schools, libraries, municipal buildings, hospitals, airports and colleges under its aegis. Hospitals saw the murals as therapeutic; schools saw them as educational. Art could be used to educate students, the poor, even prisoners to prepare for a better and more useful and fulfilling life. Artists became a bit like social workers.

CV: So tell us a bit about the murals in Gloucester City Hall.

SE: Two painters were responsible for most of the murals in the building. The first was Frederick Mulhaupt (1871-1938), born in Missouri. He first came to Gloucester in the summer of 1907 after study in Paris and New York. In 1923, he settled permanently on Rocky Neck. He was known as the “Dean of the Cape Ann School” and died of a heart attack in 1938 at his easel.

Frederick Milhaupt: De Champlain Surveys ‘Le Beauport’ (1936)

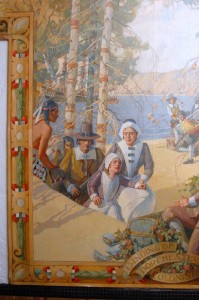

Frederick Mulhaupt: Landing of Dorchester Colonists – 1623 (1936)

Mulhaupt painted these two historical murals for the former Central Grammar School across the street from City Hall. The first depicts Samuel de Champlain landing in Gloucester Harbor in 1606 and naming it Le Beauport, the beautiful port. Following de Champlain, a group of English from the Dorchester Company landed at Half Moon Beach and set up in what is now Stage Fort Park. The settlers worked on establishing fishing and trading industries, built fish treatment stages, farmed, and built ships using the wonderful oak trees of Cape Ann.

CV: As an artist yourself, how would you describe these murals to someone who’d never seen them?

SE: Mulhaupt’s depictions of these historic events highlight idealized, heroic and upright individual figures. The dramatic use of shadow, flatness of paint application and muted color contribute to their solidity. Foliage and figures alike seem to exist in two frozen moments of history. The borders, stylized and muted as well, isolate the scenes, almost as if they are illustrations in a book on Gloucester history.

CV: What about Charles Allan Winter whom you mentioned earlier? He painted the majority of murals we see in City Hall.

SE: Winter immortalized ordinary workers and community members – teachers, ex-mayors, high school students, city workers, etc. He used real models for portraits. Poetry was originally painted for the Central Grammar School. In the academic schools, they showed the history of civilization and culture. So here we have an academic school mural.

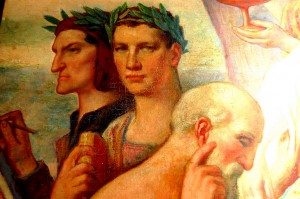

Charles Allan Winter: Poetry (1936)

Poetry is an allegorical piece, a symbolic depiction of the spirit of poetry. Winter used figures from classical mythology, as well as Dante and Virgil, the fathers of poetry as his subjects. At least two of the figures are Greek muses — Clio, the Muse of history holds a scroll; Terpsichore, with a Lyre, was the muse of dance and choral songs. Between them is a woman pouring water from a jug, perhaps symbolizing rhythm, perhaps poetic fertility. The figure of Life trims a lamp, bringing light to the mind, and imagination is on a winged horse, a horse of fantasy and flight. Dante and Virgil stand to the left, serious and confident men.

The color in this mural is intense, as opposed to the muted tones in Mulhaupt’s. Winter used a color system espoused originally by Robert Henri, the great art teacher and leader of the Ashcan School group of painters. There were 24 evenly spaced hues and a formula for achieving a color harmony. John Sloan, another proponent described it like a musical system, with 12 major color divisions corresponding to a 12 tone system in music.

CV: There are several other murals you could talk about but, to close, let’s focus on Winter’s rendering of the founding of the city itself.

Charles Allen Winter: The Founding of Gloucester (1934)

This was the first mural painted in City Hall, by the PWAP. The uppermost figures on the right represent the earliest European settlers on Cape Ann, sent by the English Dorchester Co. in 1623, three years after the settlement in Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Native American who watches as the Europeans unload their supplies smokes a peace pipe similar to one found in an Essex Native American archeological dig. Old Mother Ann, a rock formation thought to resemble an old woman looking out to sea, is in the background, and Norman’s Woe, an island off the coast named for the boats that had foundered there, in the distance.

In the upper left the city fathers, the first selectmen, discuss plans for the building of Gloucester. Their faces are portraits of contemporary city officials. As they plan, carpenters build stages, now called wharves, which gave the name Stage Fort Park to the site of the first settlement. Moving down on the left, a woman with a spinning wheel, and a mother with her child — painted by Alice Beach Winter a specialist in children’s portraits — symbolize Gloucester’s weaving industry and its home life.

In the center of the painting, “History,” a gray-robed woman with a quill and book, records events. To her right is the Seal of Gloucester with its fish, sail, anchor and arm and hammer that was used until 1873, the year it became a city. At “History’s” feet, almost coming off the canvas at the edge of the frame, is “Vision,” a boy looking outward and upward, into the future.

CV: So if you had to tell people in one sentence why they should come take a look at Gloucester’s WPA murals, what would you say?

SE: The works I’ll be discussing at Gloucester City Hall emblemize New Deal philosophy regarding the role of the arts. And they also remind us of what’s important about the wonderful and too-often-dismissed aesthetics of American Scene painting. They’re well worth a visit.

Tours will begin shortly after 1:00pm both Saturday and Sunday in the lobby of Gloucester City Hall and will last approximately 45 minutes. City Hall is handicap accessible and is located at 9 Dale Avenue, Gloucester. Mural tours not appropriate for children or dogs on leashes.

The Gloucester Committee for the Arts is the steward of the New Deal murals in Gloucester, as well as the City’s own art collection. For more information go here.

Helen Epstein is the author of “Joe Papp” and “Music Talks.”

Tagged: 1930s, Cape Ann, Culture Vulture, Depression artists, Essex County, FDR, Gloucester City Hall, Gloucester murals, Susan Erony, Trails and Sails Festival, art in New England, murals, public art