Book Review: “She Come By It Natural” — Dolly Parton, Feminist Icon

By Chelsea Spear

Those looking to understand why Dolly Parton is such an icon, or searching for a thoughtful and witty alternative to Hillbilly Elegy, would do well to read this book.

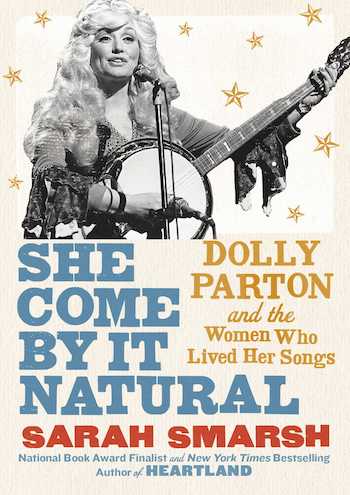

She Come By It Natural by Sarah Smarsh. Simon & Schuster, 208 pages, $22.

Buy at Bookshop

Over the past five years, Dolly Parton has been experiencing a career renaissance. The multihyphenate country music star has not only headlined the influential Glastonbury Arts Festival in England and made a special guest appearance at Newport, she’s also produced and starred in a hit Netflix series; been the subject of the blockbuster podcast “Dolly Parton’s America”; given away the one millionth book with her literacy nonprofit, the Imagination Library; read bedtime stories on YouTube during the pandemic; taken over social media with reaction GIFs and the Dolly Challenge meme; and underwritten coronavirus vaccine research at Vanderbilt Hospital. In She Come By It Natural, journalist Sarah Smarsh looks at another underrated role Parton has played — that of feminist icon.

Over the past five years, Dolly Parton has been experiencing a career renaissance. The multihyphenate country music star has not only headlined the influential Glastonbury Arts Festival in England and made a special guest appearance at Newport, she’s also produced and starred in a hit Netflix series; been the subject of the blockbuster podcast “Dolly Parton’s America”; given away the one millionth book with her literacy nonprofit, the Imagination Library; read bedtime stories on YouTube during the pandemic; taken over social media with reaction GIFs and the Dolly Challenge meme; and underwritten coronavirus vaccine research at Vanderbilt Hospital. In She Come By It Natural, journalist Sarah Smarsh looks at another underrated role Parton has played — that of feminist icon.

She Come By It Natural covers similar ground to Jad Abumrad’s Peabody Award-winning podcast “Dolly Parton’s America.” Where Abumrad went wide, spotlighting African country singers and Dollywood theme park employees alongside academics who study rural American women, Smarsh goes deep, describing the experiences of rural American women in the Rust Belt (where Smarsh grew up) and Appalachia (Dolly’s home base). For Smarsh, Parton’s feminism is personal. She frequently writes about her grandmother, who’s the same age as Parton and from a similar socioeconomic bracket, to describe how Parton’s songs speak to the lives of rural women. When Smarsh and her Grandma Betty attend a Dolly Parton concert in 2016, she reflects on how the experience was “like watching two women’s lives with roughly similar beginnings but very different experiences occupy the same space.” For women like Grandma Betty, who “come from a place where ‘theory’ is a solid guess about how the coyotes keep getting into the chicken house,” Parton sees and elevates their lived experience. Likewise, Smarsh’s observations about how her extended family’s lives dovetail with the stories in Parton’s songs give the book a credibility and illuminate the experiences of women who have been overlooked by contemporary feminist studies.

Parton has frequently deflected political statements with jokes about her exaggerated feminine appearance. When Billboard magazine asked her if she’d read Sheryl Sandberg’s female-friendly business guide Lean In, she answered, “I’ve leaned over.” Smarsh doesn’t think Parton’s feminism is expressed through political statements, but in the lyrics to her songs and the way she’s conducted herself throughout her career. At a time when Ms. magazine had only started publication and Roe v. Wade had yet to go before the Supreme Court, Parton was writing songs about domestic violence and out-of-wedlock pregnancy “that were too true to even get played on the radio,” Smarsh observes. Parton’s personal storytelling and vivid depictions of women from rural America were a way to make feminist issues accessible to women whose lives were unaffected by the movement. By writing extensively about “Tomatogate” — radio programmer Keith Hill’s controversial statements about women’s airplay on country music radio — she shows how Parton’s portrayal of women’s experiences remain relevant.

For many generations, Dolly Parton is seen as a secular saint… albeit the kind who would tell you a dirty joke or two. Smarsh’s chronicle of Parton’s good deeds supports this image of the singer. Only in the book’s final chapter do we get some fair criticism of how Parton has handled race. Smarsh explains the controversy around the Dollywood attraction Dixie Stampede and describes the singer’s cringeworthy appearance on a 2013 episode of The Queen Latifah Show. (“In inviting Latifah to battle, she referenced belonging to a ‘redneck mafia,’ apparently without realizing this might conjure for some viewers the violent and deadly horrors of white supremacy in the South.”) Like any beloved figure, Parton has a complicated side. Smarsh’s criticism might have been even stronger if she had woven it throughout the book instead of leaving it to end, where it could leave a bitter aftertaste for some. Since this isn’t an official biography of Parton, I had hoped Smarsh would look at some of the concerns Jessica Wilkerson raised about Dollywood employees. Unfortunately, those issues didn’t make the book.

Ultimately, however, She Come By It Natural is a deep examination of both a beloved American performer and the experiences of a part of the country that’s seen by many as only a convenient punchline. Those looking to understand why Dolly Parton is such an icon, or searching for a thoughtful and witty alternative to Hillbilly Elegy, would do well to read this book.

Chelsea Spear has written for the Brattle Theatre’s Film Notes blog, the Gay & Lesbian Review, and Crooked Marquee. She lives in Boston.