Arts Feature: When Aretha Franklin Snapped Me

[Editor’s Note: Just over a year has gone by since Aretha Franklin passed away. On September 14 and 21, Bostonians have a terrific opportunity to experience her brilliance at screenings of the powerful 2018 documentary Aretha Franklin: Amazing Grace at the MFA Boston. It seems like an appropriate time to post this personal reminiscence of the singer. — Bill Marx]

By Daniel Gewertz

Looking at that photo now, soon after the anniversary of her death, Aretha’s shutter-snap of connection with me seems a blessing.

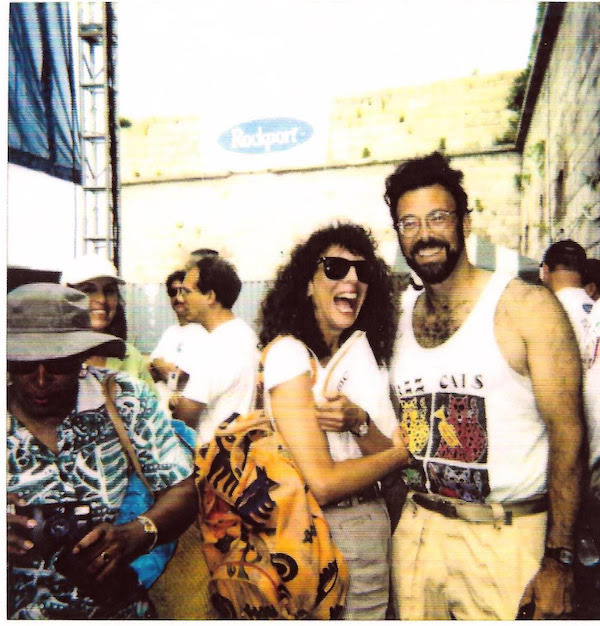

The picture that Aretha Franklin took.

I never met Aretha Franklin, but once, in the late ’90s, she took my picture.

The scene was the briefly-lived Newport R & B Festival. As a music journalist, I was allowed backstage, or, more accurately, to a portion of the back that shrank as the wattage of star increased. With Aretha, it was more like side-stage. Before Aretha’s set, I was lucky enough to catch a good look at her as she exited her trailer and climbed the steep stairs to the stage. She wore a dress of nearly phosphorescent pink, a gaudy wedding-cake of an outfit that made her seem mountainous.

It was about an hour after her show that word spread in the press-pit that Ms. Franklin was about to descend her trailer steps and exit the Fort Adams grounds.

My inner-fan overpowered my journalist role. Along with a friend, I darted from the front of the stage and scurried over to a good spot in back, directly in front of a provisional wooden railing: the perfect position to see the Queen of Soul walk among us.

We barely recognized Aretha when she emerged. The elaborately constructed pink dress was replaced by a simple pastel pants suit. The transformation startled – the woman before me looked of medium height, little more than medium weight, a calm presence, nondramatic in demeanor. She could have been a suburban matron. As she approached the wooden railing and faced the perhaps 50 fans and festival workers, she flashed what seemed to be a mischievous smile Her assistant handed her a Polaroid camera. And then Aretha proceeded to snap a few photos of her fans, glancing at each newly ejected Polaroid print before her assistant collected it. Then the process would repeat: a look, a snap, a glimpse of the picture as it exited the device.

I looked, questioningly, at Aretha’s assistant. “It’s just something she likes to do sometimes after shows,” the small woman said to me with a shrug. At that moment, Aretha pointed her Polaroid directly at me and my friend and snapped the shutter. She smiled at me, or at least in my general direction.

Within moments, her assistant sidled up to me, conspiratorially, at the railing. “Do you want your picture?” she asked, Polaroid in hand. I said yes, and she maneuvered the small photo toward me, behind her back, her left wrist curled up, the very model of surreptitiousness. Her stealth may have been partly theatrical, but it was clear she only chose to covertly slip the occasional photo to a fan instead of delivering it to her boss. “She has a lot of them,” she whispered to me. “She won’t miss it.”

Aretha appeared to be enjoying herself. This picture taking may have been eccentric, but the odd turnabout of the star/fan roles didn’t seem a satirical move on her part. (It was quite unlike the deadpan antics of Leon Redbone, a droll revivalist of ancient music who took photos of his audiences mid-performance.) Aretha wasn’t out to make an absurdist statement about the nature of idolatry. It seemed she was merely recording the moment.

Given enough time, memories can become as distilled as snapshots. They exist in the mind as a single captured image, a still photo of the brain’s limbic system. Looking at Aretha’s photo from the vantage of 22 years, I am struck that this may be the only photo taken of me at a rare time of animal peak, what I remember as the fittest summer of my life. I am 47 here, unusually slender, toned by daily bike-riding and gym attendance. It is less than a year before the first serious illness visits my life. It may be my ego talking, but I can’t help but wonder if Aretha Franklin was drawn to the happy, thriving fellow who stood before her, that it was not a complete accident that her Polaroid viewfinder found my thrilled, grinning face. Looking at that photo now, soon after the anniversary of her death, Aretha’s shutter-snap of connection with me seems a blessing.

Was Aretha’s picture-taking penchant a simple desire for the same fun her fans had? Or did it run deeper? Known for her superstitions, perhaps she wished for a pictorial record in order to make her fan-base, and its love, more solid, more abiding. In that pre-smart-phone era, the Polaroid was the lone (near) instant way to capture a two-dimensional evidence of life. Maybe Aretha – a woman who knew the rough and dark of life long before she became a luminary – desired a confirmation of her stardom not merely from photos of herself, those records of glories, but also of blemishes. Perhaps she wanted proofs of a perfect, permanent fandom, her own image out of the frame entirely.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the l970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.