Book Review: A Concise, Conscientious Guide to the Life and Work of Alfred Stieglitz

By Peter Walsh

The book will stand as a good first stop for anyone interested in Alfred Stieglitz, 20th-century photography, or American modern art.

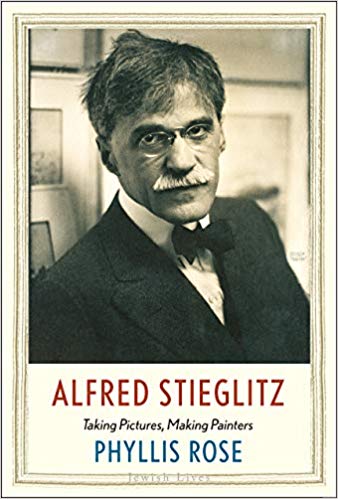

Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters by Phyllis Rose. Yale University Press, 272 pages, $26.

In 1918, photographer and gallery owner Alfred Stieglitz convinced a thirty-year old art teacher from Canyon, Texas, to give up her job, her hard-won financial independence, her teaching career, and her home to move to New York City. Her name was Georgia O’Keeffe.

Stieglitz, well past fifty and married at the time, said he was concerned for O’Keeffe’s health, poor for the past several years. He wanted her to get proper medical treatment in Manhattan. His real motivations were far more complicated. Immediately, their multi-layered and constantly changing relationship became even more so, perhaps the richest, most lasting, and most productive partnership in the entire history of modern art.

The pair quickly became lovers and each other’s inspiration and muse, O’Keeffe was the model for some of Stieglitz’s most important photographs, including a stunning series of nudes considered among his greatest work. Stieglitz became O’Keeffe’s agent and tireless promoter. He provided the encouragement and financial support she needed to become a celebrated artist. Eventually, he became her husband as well, though not always a faithful one. At first, he supported her so she could paint full time. In later years, her artistic success helped subsidize Stieglitz’s many projects to promote American art and artists.

Had they never met. Stieglitz might have slid more and more crankily into old age. O’Keeffe might have remained an obscure spinster art educator, chair of the art department at West Texas State Normal College, and been forgotten. But there is, of course, no way to know for sure.

The Stieglitz-O’Keeffe question highlights one of the many thorny issues that tend to obscure Stieglitz’s career from the public. So much of it involved promoting other artists — besides O’Keeffe, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Arthur B. Davies, Arthur Dove, Max Weber, and the early 20th-century European modernists — that Stieglitz tends to stand in his own shadow. There is, about all of this, a “It’s a Wonderful Life” lack of resolution: if Stieglitz had never lived, what would have happened? Would New York have remained just the money grubbing “city of ambition” he both loathed and loved? Would New York have become the center of world art without him? Would American art have stayed as conservative, provincial, and slavishly subordinate to Europe as Stieglitz found it?

Much as Stieglitz hated the idea and mission of the Museum of Modern Art, would that institution have ever been founded without the example of his pioneering New York gallery, 291, decades earlier?

Stieglitz’s tireless work as a gallery owner, writer, editor, tireless talker, and art evangelist also obscures his work as a photographer. So do, ironically, his long decades of working in the medium. By the time of his death, Stieglitz’s early, pictorialist photographs— path-breaking at the time they were created— seemed dated. His significant work in the technical aspects of photography had long been surpassed.

Stieglitz’s photographic career was also eclipsed by his own somewhat contradictory efforts. Always ostentatiously contemptuous of money and wealth, despite the fact that a family fortune supported his education and work, Stieglitz disliked selling his work to collectors. Instead, he asked for donations to a fund he used to support artists. In return, he made a “gift” of some original prints to the donor. On the other hand, when a museum like The Metropolitan, asked for a donation of his work, Stieglitz treated the request as a insult. Being paid was a sign of respect, both for Stieglitz himself and for his medium, which he had worked all his life to promote as a serious art form, worthy to hang alongside masterpieces of painting and sculpture in major museums.

After Alfred’s death, O’Keeffe made major donations from her husband’s archive to museums around the country. The gifts came, however, with strings attached, strings that severely limited how often the prints could travel for exhibitions or be reproduced. Thus, for years, an in-depth study of Stieglitz’s originals was a possibility mostly for specialists who were willing to travel to museums holding his work. The contrast with O’Keeffe couldn’t be stronger: her paintings and drawings, with Stieglitz’s active encouragement, always sold well, were exhibited often, and remained very popular throughout her career and after her death. Although both Stieglitz and O’Keeffe are remembered as pioneers, O’Keeffe is widely revered as the “mother of American modern art.”

Literary critic Phyllis Rose does an admirable job handling the astonishing breadth and many contradictions in Stieglitz’s life and work in her new biography, Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters. She devotes useful attention to his formative years as the son of a wealthy Jewish family in New York City’s boom years after the Civil War, his studies of the physics and chemistry of photography in Germany, and his unhappy first marriage. She also gives a strong sense of his vigorous campaigns as a promoter of photography, his efforts in early photographic associations, and his critical role as editor, publisher, and contributor for such key journals as Camera Work. She is good on navigating, for general readers, the constantly changing aesthetics of early 20th-century art and American taste.

Alfred Steiglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe. Photo: Perry Miller Adato.

But the appearance of her book in Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series does present other challenges. Yale’s apparently limitless series, which covers major Jewish figures, religious and secular, from the beginning of recorded history to the present, is clearly aimed at general audiences, not specialists. Produced in a uniform format, most volumes are pegged to a middling length, usually between 200 and 300 pages (Moses, Solomon, Trotsky and Peggy Guggenheim, for example, all clock in at 240; Stieglitz is 259, including notes and index). The typical standard scholarly biography, by contrast, can easily run three or more times this length, and even to multiple volumes. The Yale format makes for a more readable, concise presentation. But it’s a tough challenge for authors.

As Rose points out in a note, the primary and secondary sources on Stieglitz are massive: “The difficulty in writing about him,” she explains, “is not the absence of information but the abundance of it.” The archive of the Stieglitz-O’Keeffe correspondence alone runs to more than twenty-five thousand pages. The first of three projected volumes of “selections” from these letters, published in 2011, runs to almost 740 pages.

Admirably carried out, Rose’s massive efforts at compression inevitably leave her treatment of some key parts of Stieglitz’s life feeling a bit thin. Chief among these is probably the Stieglitz-O’Keeffe relationship itself — immensely long, complex emotionally, professionally, and intellectually, embracing love, passion, jealousy, resentment, inspiration, disappointment, support, distance, and remarkable endurance. Also, given that so much of Stieglitz’s work with artists involved talking — pompous, eloquent, encouraging, and dismissive at turns — one could have wished for a bit more in his own voice. Nevertheless, the book will stand as a good first stop for anyone interested in Stieglitz, 20th-century photography, or American modern art. Those readers will thank Rose for being such a concise and conscientious guide.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. As an art historian and media scholar, he has lectured in Boston, New York, Chicago, Toronto, San Francisco, London, and Milan, among other cities and has presented papers at MIT eight times. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in anthologies. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than eighty projects, including theater, national television, and such award-winning films as Spotlight, The Second Life, and Brute Sanity. He is a graduate of Oberlin College and Harvard University.