Fuse Remembrance: Heda Kovaly

Translating what became Under a Cruel Star was a labor of love as well as a work of feminism. There were few memoirs around of a life that spanned Nazism and Stalinism. None was written by a woman.

Readers of today’s New York Times found a remarkable story on the obituary page: the eyewitness account of a twentieth-century life by a Central European, literary woman who survived both Hitler and Stalin.

I met Heda Kovaly in 1985 through a mutual friend, Wellesley history professor Jerry Auerbach, who knew her from the Harvard Law Library where she was a beloved resource for hundreds of students and professors.

Like Heda, I was born in Prague. Like my mother, Heda had been deported from that city during the Nazi Occupation, survived the camps, and returned to Czechoslovakia. Like my mother, she hoped that the worst part of her life was over and that she could start afresh.

Then came the Communist putsch of February 1948. Unlike my parents who were able to bundle me up and get to the United States that summer, Heda remained in Prague. Her husband became a member of the Communist government until that government turned to a series of Stalinist show trials. Rudolf Margolius became one of the 11 Jews hanged after the infamous Rudolf Slánský trial.

Our mutual friend thought we should meet and so we did. Heda had written an account of her life in Prague until 1968 in Czech. As Andre Orzoff wrote in a review, “Kovaly’s moving story was first published twenty years ago, in the shadow of the Prague Spring. Initially, Kovaly’s book served only as an extended pro-logue to a philosophical treatise on the events of 1968 by emigre philosopher Erazim Kohak. In an unsuccessful attempt to make these two texts more parallel, Kovaly’s work was given the same chapter headings and subheadings as Kohak’s: an artificial and un- wieldy division of Kovaly’s tense, sparely told story. ”

Alfred Kazin, reviewing the English-language edition for the New York Times Book Review in 1973, noted the imbalance in the volume. His review all but ignored the treatise, commenting that “[Kohak’s] chapers are rational, sensible and intellectually admirable without touching the heart. Heda Kovaly’s chapters are the burning facts.”

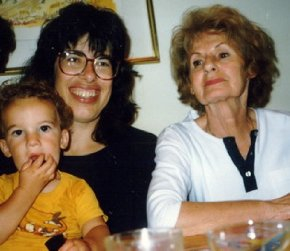

I agreed and agreed as well to work with Heda on a new translation, in fact a new version, of her memoir. I was not a translator, but I was pregnant with my first child and unable, I then thought, to generate any more creation of my own.

Translating what became Under a Cruel Star was a labor of love as well as a work of feminism. There were few memoirs around of a life that spanned Nazism and Stalinism. None was written by a woman. And there was another subtext: I had grown up in New York City, among children of black-listed Communists who were using the same survival strategies that Heda used in Czechoslovakia.

Working with Heda was not a piece of cake. She was an accomplished translator with a long bibliography of credits to her name. She was also a woman of the Zsa Zsa Gabor generation—petite, elegant, flirtatious, and self-effacing, insisting that I drop my feminist ideas and recognize my husband for the saint she thought him to be.

I, often despite her, was engaged in the project of writing women back into history, improving my Czech, and learning about the fate I’d so narrowly escaped when my father declared that the Communists were Nazis in a different colored uniform and got us out of Prague in 1948.

Heda and I translated her work at our dining room table. A year later, my husband and I published it ourselves and wrapped 6,000 copies in mailers at that table. Then we hit the phones, got people to read it, and were able to interest Anthony Lewis in reviewing it. It was his review that helped sell the book to Penguin in the U.S. and many publishers abroad.

Critic Clive James called it “necessary” reading, and over the years Under A Cruel Star has been adopted as a university text in international relations and European history as well as in memoir courses. It has been inspiration to readers everywhere but particularly, after the Velvet Revolution, to those in her beloved Prague.

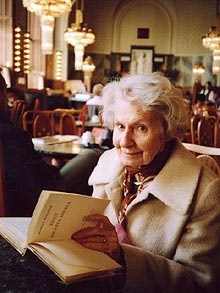

Heda returned to live there in 1996. Although she spent nearly three decades in the Boston area and made several deep friendships here, she never stopped missing her home. She was able to live in a beautiful apartment near the center of town and to walk the streets she had walked as a girl.

May her memory be a blessing. May her book continue to inspire readers and writers.

=======================================

Helen Epstein has written a biography of Joe Papp. Her translation of Heda Kovaly’s memoir of Stalinism, Under A Cruel Star, is also available on amazon.com. Order though the link below and The Arts Fuse receives a small percentage of the sale.

Deeply touched by your memories of your friendship with this extraordinary witness to history and excited to read Under A Cruel Star!

Unlike Heda and Helen Epstein I was not born in Prague but in Holland.Later I moved to Canada where I read Under a Cruel Star in 1997.

Via a remarkable series of coincidences and circumstances we met in Prague and became friends.

We wrote and saw each other every time I visited Prague.

I bought at least 25 copies of her book to pass on to friends and colleagues and it never failed to make a deep impression on all who read it.

I will miss Heda terribly. I did not speak to her for several years due to her illness. But she was never far from my thoughts.

Her strength, her courage and love will remain with me until the end of my days.

Rest in Peace dear Heda.

Love you.

Titi