Book Commentary: “Fahrenheit 451” and Cultural Betrayal

It never occurs to Ray Bradbury that, by just championing the great works of Western Civilization and consigning pop culture (notably science-fiction) to the flames, he’s exercising his own pernicious brand of censorship.

By Patrick Pritchett

Book burning has been going on for a surprisingly long time. Since the invention of books, in fact. In his highly readable A Universal History of the Destruction of Books, Fernando Báez grimly observes that humans have been burning books and papyrus scrolls, (or smashing clay and stone tablets) since the invention of writing as a means for repressing ideas and asserting cultural dominance over a conquered society. Knowledge is as fragile as empire.

You might be forgiven, then, for thinking that Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 is about fighting the evils of censorship. After all, the back cover copy declares it to be a “classic novel of censorship and defiance” and it’s generally taught this way in high schools. (The theme was emphasized in the recent film version, directed by Ramin Bahrani, broadcast on HBO in May.) But Bradbury himself never took this line. According to the Christian Science Monitor, the author declared that “Fahrenheit’s not about censorship. It’s about the moronic influence of popular culture through local TV news, the proliferation of giant screens and the bombardment of factoids. We’ve moved in to this period of history that I described in Fahrenheit 50 years ago.”

This perspective places his most famous novel squarely in the middle of the Cold War’s anxiety about the status of culture. Following the same path as critics Russell Lynes and Dwight Macdonald, Bradbury was intent on creating and then policing the boundaries between highbrow, middlebrow, and lowbrow: fuddy-duddy terms that, once upon a time, before the leveling effect of postmodernism, carried considerable cultural weight. Examining Macdonald’s one-man war on the pseudo-highbrow, Louis Menand wryly notes that “the liberal highbrow, the person who favored an immediate ban on nuclear weapons and refused to have a television in the house, was a wonderful mid-twentieth-century type.” He cites his father as such a type. Ray Bradbury was another.

Fahrenheit 451 wants to be a chilling portrait of a future totalitarian state in which reading books is banned (though not the act of reading itself, oddly) and the books themselves burned. In truth, it’s a lament for the demise of high culture. Awkwardly didactic at best, the novel chastises the subscribers of Reader’s Digest and other middlebrow cultural elements, like TV, which Bradbury castigates for eroding the proud bulwarks of high culture. Seen from that perspective, Fahrenheit 451 (the temperature at which paper ignites) only touches on the terror of the modern state — Bradbury real agenda, pushed through without his trademark whimsy and lyricism, is to show how we’ve become hypnotized and passive by the empty allure of mass culture.

In Fahrenheit 451, TV, not authoritarianism, is the real villain. The hero’s hapless wife, Millie (rhymes with “silly”), is narcotized by her shows (here Bradbury anticipates the inanity of Reality TV). The world of 451 isn’t quite post-literate, but seems to be moving in that direction. Millie’s dependence on sleeping pills – when we are first introduced to her, she’s OD-ed – is made out to be no different than her addiction to TV. The gendering of middlebrow culture – TV is for anesthetizing women, and not a proper activity for viral men – is one of the novel’s more deplorably dated aspects. As Captain Beatty, the novel’s heavy, informs Guy: “Films and radios, magazines, books leveled down to a sort of pastepudding norm … Condensations. Digests. Tabloids. Everything boiled down to the gag, the snap ending.” In some ways, Beatty’s argument about rampant dumbing down anticipates the rise of social media and the Twitter presidency. Above all, though, the job of the book burners is to eradicate “those who want to make everyone unhappy with conflicting theory and free thought.”

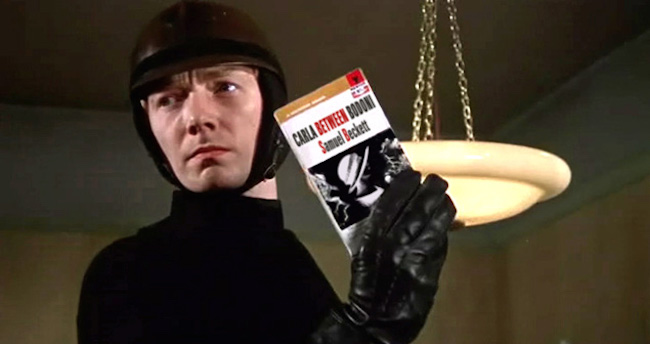

Burning up a volume of high culture (by Samuel Beckett) in François Truffaut’s 1966 film version of “Fahrenheit 451.”

But it wasn’t just Hollywood moguls who were losing sleep over the emergence of TV in the early 1950s. (In 1950 only 9% of American homes had TVs; by 1960 that number had grown to a staggering 90%). The intellectual elite worried a lot about its pernicious effects, too, even though FCC Chair Newton Minow’s “vast wasteland” speech was still eight years off. In 1954, mandarin Theodor Adorno weighed in on the subject in his essay“How to Watch Television,” in the Spring issue of The Quarterly of Film, Radio and Television. Characteristically, Adorno identifies the threat TV poses as one of reification – a form of ideologically-driven social amnesia – through the pervasive use of stereotypes on TV. Saturated by these caricatures, viewers, he warns, “may not only lose true insight into reality, but ultimately their very capacity for life experience may be dulled by the constant wearing of blue and pink spectacles.” Adorno concluded that culture “now impresses the same stamp on everything. Films, radio and magazines make up a system which is uniform as a whole in every part.” This homogenizing media sphere is 451’s true target.

In 1966, French New Wave director Francois Truffaut decided to adapt Bradbury’s novel to film. What resulted was probably his stiffest film; it’s certainly his least characteristic one. Even so, he manages to breathe some life into Bradbury’s heavy-handed social message through some inventive camera work that fetishizes the book-burning fire brigade in their black outfits and incongruously innocent looking red fire truck. Looking back, Truffaut’s 451 seems to have been the result of his desire to respond to compatriot Jean Luc-Godard’s earlier – and far superior – sci fi-noir thriller, Alphaville. Alphaville is much smarter at playing with the conceits of a modish futurism than 451, although Truffaut, following Godard’s lead, makes excellent use of present day settings to suggest the gleaming and anodyne metropolis of tomorrow.

As in the novel, the film follows the conflict of book-burner cum fireman Guy Montag as he wrestles with his conscience and gradually undergoes a conversion from powerful repressor to underground resister. Dramatically, it turns out to be a lackluster transformation, devoid of conviction and suspense. This is partly the fault of Bradbury’s narrative, partly due to the miscasting of Truffaut veteran Oskar Werner (Jules and Jim), who assays the befuddled Guy with his usual mordant Weltschmertz. Julie Christie plays a dual role here, filling in as both wife and mistress, status quo seeker and subversive agitator. It may strike one as merely a clever gimmick, but Truffaut seems to be implying that both positions contain elements of seduction and distress for the hero.

The movie is almost, but not quite, dull. Unlike the novel, Guy’s giving into the desire to read forbidden books is presented fait accompli. There’s never any genuine build up of suspense, just a vaguely ominous sense of something sinister about to happen. Only it never does. The storyline is weakly resolved – petered out would be more accurate – as compared to the slambang climax of the novel. But at least we’re spared the dreadful business of the Mechanical Hound (which sniffs out traitors) and the disgraceful eugenicist notion that humanity could be regenerated by the purgative fires of a nuclear Armageddon – the perversely optimistic note on which the novel closes.

Firemen doing their duty in 2018’s “Fahrenheit 451.”

To Bradbury’s credit, he sets out to attack intellectual and moral complacency. Though it’s doubtful that society would blossom into maturity overnight if everyone put aside Lee Child and J.K. Rowling and took up Kant and Jane Austen instead. In that sense, 451 anticipates the canon wars of the ’80s — cheering for the conservative side. Ironically, for a piece of genre fiction, it fails to take into account the vitality and subversive power of popular forms of culture (music, films). There’s no acknowledgement of the obvious: that the interplay between highbrow and lowbrow feeds into and invigorates the mainstream.

Instead, Bradbury’s vision of culture is blandly purist. There’s plenty of room for Plato, Dickens, and other elitist faves (though Dickens was often a shamelessly manipulative entertainer and Plato banned the poets). But no space for science fiction and other less respectable forms of culture. Bradbury inveighs against the evils of repressing free thought, but it never occurs to him that, by just championing the great works of Western Civilization and consigning pop culture (notably science-fiction) to the flames, he’s exercising his own pernicious brand of censorship.

Patrick Pritchett has been writing about film and literature since 1990. Before entering the academic world, he worked in script development for James Cameron and Kathryn Bigelow. He is the author of several books of poems, most recently Orphic Noise and teaches at Westfield State University.

Tagged: Fahrenheit 451, Patrick Pritchett, Ray Bradbury, culture-wars

Trust the art, not the artist. I don’t quite agree with what Bradbury said about the meaning of his book fifty years after the fact. Among many things, it is about censorship. As for sci-fi, I’m not sure that Bradbury was ever comfortable as a sci-fi writer since he admittedly knew nothing about science at all, or technology, and didn’t drive a car.

“It never occurs to Ray Bradbury that, by just championing the great works of Western Civilization and consigning pop culture (notably science-fiction) to the flames, he’s exercising his own pernicious brand of censorship.”

No. He is engaging in cultural critique, not censorship. Critiquing something one doesn’t like is not tantamount to “censorship.” I would think someone posing as a writer and literary critic would have a clearer understanding of what “censorship” actually means. Apparently you think it means “anyone or anything that disagrees with me or my literary taste.”

Read the sentence carefully. My understanding of the ending of the novel is that the literary works that will survive in the future (via the memories of men, but let’s not examine the exclusion of women) are major works of Western Civ. Genre works (including Bradbury’s) will be gone — consigned to the flames. Sounds like cultural critique crossing the wish-fulfillment line to Nazi-like censorship. Couldn’t we have a geezer or two memorize a mystery or sci-fi novel?