Book Review: “The Ghosts of Galway” — Fighting an Irish ISIS

Jack Taylor is a Beckettian character on the skids; he can’t go on, and yet he goes on.

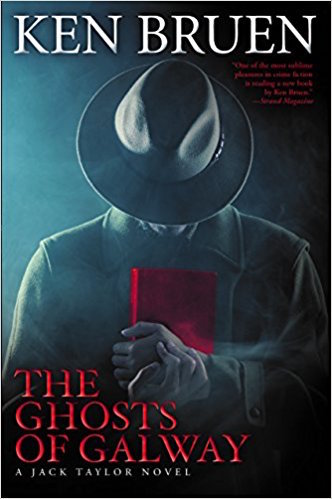

The Ghosts of Galway by Ken Bruen. Atlantic/Grove, The Mysterious Press, 336 pages, $25.

By Lucas Spiro

Former police officer Jack Taylor has had a very rough go of it. In The Ghosts of Galway, Irish writer Ken Bruen’s savage new novel, his venerable anti-hero has recently been diagnosed (wrongly, it turns out) with a fatal disease. He is also recovering from a failed suicide attempt. These two near brushes with death (which is nothing new for Taylor, if you’ve read any of the other books that feature him) are typical of his complicated relationship with survival. He is a Beckettian character on the skids; Jack Taylor can’t go on, and yet he goes on.

Taylor believes his failed suicide attempt is the culmination of his being “a sad sad fucker.” His prospects dim, he tries to pull himself out of his personal mire by taking a job as a security guard for a private company. He keeps watch over a dockland warehouse in Galway and he doesn’t hold out much hope for rising above his new occupation. For him, “the years of fuckups, pain, mutilation, grievous loss would, you think… Lead to wisdom? Like fuck. Led me to a job as a security guard. Suicide by boredom.” Deluged by addictions (primarily whiskey), Taylor is a man whose brutal life, and its many ghosts, are catching up with him.

His new job offers one consolation. He is able to read on the job. Taylor is an avid reader, and his bookish disposition provides Ghosts with a compelling sense of self awareness, without being pretentiously meta. (Bruen doesn’t want to be caught writing a “literary” story — but books, and their effects on reality, are a constant theme.) Taylor is fascinated by language (Bruen has taught English all over the world), and there is a running commentary the changing speech of the Irish, and how that transformation reflects transatlantic pressures. For example, Taylor recognizes the Americanization of Irish-English: English itself has always been an expression of hegemony, first from British colonization, and now from the import of US popular culture. In one scene, a barfly is reading a tabloid article about football (soccer) manager Alex Fergusson’s new book. When Jack asks if the volume is about soccer, the barfly explains that it is about “how to succeed in life,” which means that Fergusson has “gone American.”

A book is also what gets Taylor into trouble again. His reputation as a reader, as well as former cop and sometime dogsbody for hire, precedes him. Soon, Jack’s boss, a wealthy Ukrainian (probably an exiled oligarch) who goes by the name of Alexander Knox-Keaton, summons him. A high-ranking bishop in the Vatican has died, and his assistant, the “rogue priest” named Frank Miller, has absconded with something called The Red Book. He is hiding out somewhere in Galway. The volume itself is supposedly “the first true work of heresy,” but was actually used “by the Church as a sinister scare tactic to keep outspoken priests in line.”

This sounds like an Irish version of a Dan Brown set-up. Both Bruen and his protagonist sense the danger of a looming formula. Taylor thanks his boss for the chance to go down the “Dan Brown alley” but, at least initially, he’s not interested. The similarities stop there. For one thing, Bruen is a good writer. The point of Ghosts isn’t to whoop-up a conspiracy. Brown makes the individual feel small and insignificant in a way that invites, even demands, a hero, or worse, a god. Bruen makes the individual feel small and insignificant in a way that binds him or her to others because, ultimately, there are no heroes and everyone suffers.

Bruen’s Galway is populated with some truly deranged characters, and most of them have sinister designs on Taylor. Alliances are cheap, and life is even cheaper. A group of religious zealots (primarily disaffected young men) devoted to a rogue priest begin dumping dead animals in Eyre Square — a horse, a sheep, and a swan — and send cryptic messages to a local newspaper. These men are the titular ghosts of Galway, “a combination of Old Testament, ferocity, fundamentalism, and your plain run of the mill violence,” an “Irish ISIS” that wants “to return to the Latin Mass, parental authority, the Ireland of the fifties.”

Author Ken Bruen. Photo: Magnet Magazine.

These ghosts, however, are no match for the protean Emily, a “Goth-like crazed girl” who is either “Bipolar” or “Byronic.” She has a lengthy list of potential victims that may or may not include her parents. Emily’s unpredictability gives her a lethal advantage over Jack, the police, and other criminal elements. She’s also half Jack’s age, so there’s a youthful energy to this femme fatale’s viciousness.

For Bruen, this reactionary, populist movement is a virulent response to the alienation generated by late capitalism, to the unquestioning devotion of politicians and policy makers to the financial markets. Post-recession Ireland is one where the new “Irish pastime” is litigation. Taylor concludes that “Celtic Tigers, crushing financial reparations, and water bills killed our very spirit.” But there is no turning back. The past has either vanished or is weirdly estranged from the present. Nostalgia is being pushed aside by the new language used by the younger generation, the drinks it orders and the cigarettes it smokes.

Bruen’s prose has the immediacy you would expect from a noir novel. Many people are choosing non-genre fiction to help them deal with the current horrific political reality, but books like The Ghosts of Galway, and noir specifically, should really be at the top of their reading lists. Noir is uniquely capable of responding to the intersections of criminality and politics, of sucking the grime to the surface while pulling the seamy superstructure back down to earth. While Bruen doesn’t offer much hope or solutions, there is nothing fake in his unfiltered vision of our violent world.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Lucas:

Thank you from the bottom of my bedraggled heart

Glor agus bheannacht

Ken Bruen

Ken,

It was my pleasure to read and review your book. Thank you for writing it. I look forward to reading the next one.

Lucas