The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 29

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

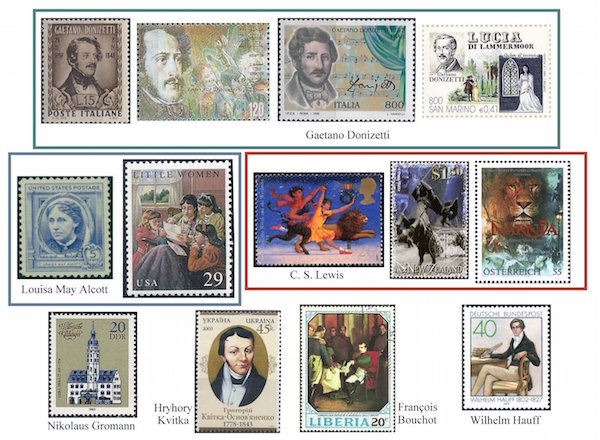

Pride of place today goes to Hans Holbein the Younger, Gaetano Donizetti, Louisa May Alcott, and C. S. Lewis. The important German architect Gottfried Semper will receive a fair amount of our attention, too, and we’ll spend time with quite a few more.

Hans Holbein the Younger was born around 1497 or so. His date of death is not known either, except insofar as it has been narrowed down to “between 7 October and 29 November 1543” (Wikipedia). So today is our last chance to fall within the window of opportunity. (Actually, German Wikipedia specifies the 29th, and that’s good enough for my purposes.) He was born in Augsburg and went with his older brother Ambrosius (you know who their father was) to Basel. There they provided woodcuts (and similar cuts on metal plates) for printers. One of the books they worked on was The Praise of Folly by Erasmus, whom Hans would paint more than once in the following years. The first stamp we see after the Self-Portrait of 1542-43 is indeed one of the Erasmus portraits of c1523 (on a stamp from Bhutan!). It’s believed that Ambrosius must have died around 1519, and Hans remained in Basel—professional trips to Lucerne and possibly Italy aside—until Erasmus recommended him to Thomas More. Holbein went to England in 1526 and made his famous portrait of More, reproduced on a stamp from the Vatican, in 1527. After a return to the continent he was back again in 1532, and it was during this period that he painted King Henry VIII and members of and visitors to the court. One of these was the Hanseatic League merchant Georg Giese (or Gisze), captured in 1532 and seen on a stamp from Burundi. A double portrait called The Ambassadors (1533) included the French envoy Jean de Dinteville, as shown on a stamp from the Kathiri State. Another French diplomat, Charles de Solier, the Count of Morette, was painted in 1534, and that piece is found on a monochrome stamp from the GDR. The less familiar portrait of Henry VIII precedes the more famous one from about the same time (c1537), very similar in pose to the one from 1540, seen on stamps of Micronesia and the UK. Several stamps make use of the famed portraits of Henry’s third (and favorite) wife Jane Seymour and his fourth, Anne of Cleves, though the latter was painted prior to her marriage to the king. Holbein survived the fall of his patrons Thomas More, Anne Boleyn, and Thomas Cromwell and received commissions from surviving courtiers until his own death, possibly from plague, in the autumn of 1543. We leave him with views of two of his sacred paintings, the Darmstadt Madonna (c1526-28) on a stamp from the Saar and the Solothurn Madonna (1522) on a pair of stamps from the Vatican. Since the birth and death dates of Hans Holbein the Elder (c1460 – 1524) are imprecisely known, I was planning to do a concurrent feature on him until I found that there were so many others demanding inclusion today that we must put off the old man until another time.

Italy has twice recognized Gaetano Donizetti (1797 – 8 April 1848) on its stamps, the first time in 1948 on the centenary of his death, then again fifty years later. One year earlier (1997), Bulgaria issued a stamp for the bicentenary of his birth. The San Marino stamp comes from a set of sixteen released in 1999, each one depicting an opera composer and a scene from one of his works.

November 29 is the birthday of Louisa May Alcott (1832 – March 6, 1888), whose early education was augmented by lessons from family friends like Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Fuller. A staunch abolitionist, Alcott was a “station master” on the Underground Railroad. She also did nursing service for six weeks at the beginning of the Civil War and would have worked longer had she not fallen dangerously ill with typhoid. As a writer she first published with the Atlantic Monthly in 1860. Prior to that she had written a book of children’s stories and a novel, but the latter work, The Inheritance, would not see publication until 1997. In the years to come she would produce many more novels and stories. Born in Philadelphia, she remained unmarried and died in Boston. Alcott’s most famous novel, Little Women, was made into an opera by American composer Mark Adamo in 1998. The portrait stamp is from a 1940 series honoring American writers, and the Little Women stamp derives from a 1993 group celebrating children’s classics.

C. S. Lewis was the author of more than thirty books, many in defense of Christianity, which he had renounced in his youth but to which he returned partly through the influence of his dear friend J. R. R. Tolkien and the book The Everlasting Man by G. K. Chesterton (who has no stamp!!). But the Lewis books that have been the biggest sellers are the Chronicles of Narnia series, and it is these that have been recalled on postage stamps of the UK, New Zealand, and Austria. The New Zealand stamp comes from a set issued to capitalize on the release of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe from the 2005-2010 film series, largely shot in that country. The Austrian stamp is also connected with the films, but I don’t know why it was issued, as none of the filming took place there. Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was born in Belfast. He lost his mother to cancer when he was nine. He briefly attended Oxford before being swept up in World War I, during which he was wounded by a British shell that killed two of his comrades. On being demobilized he returned to school. Much later in his life, Lewis met the American writer Joy Davidman Gresham, whom he married in 1956, adopting both her sons from her previous marriage. On her death, also from cancer, Lewis brought up the two boys. (The story is poignantly told, albeit with only one son represented, in the fine 1993 film Shadowlands, with Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. Sadly, Lewis’s death—and that of Aldous Huxley—was obscured by the Kennedy assassination, which happened about 55 minutes after Lewis’s collapse. Peter Kreeft has written an imaginative book (disclaimer: I haven’t read it, but it must surely be imaginative) called Between Heaven and Hell: A Dialog Somewhere Beyond Death with John F. Kennedy, C. S. Lewis, & Aldous Huxley.

Let’s return now to the century of Holbein and to his countryman (by modern standards).

Nikolaus Gromann. (While Holbein was from Augsburg, Gromann was active in Thuringia as master builder in the service of the Elector of Saxony.) Born about 1500, Gromann is credited with having built the first Reformation Protestant Church, the chapel at Schloß Hartenfels in Torgau, in 1545. The building shown on the East German stamp is the town hall of Gera, likely built to Gromann’s plan but not completed until 1576, after the architect’s death on this date in 1566 in Gotha. Under his supervision many castles, churches, fortifications, roads, bridges, and fountains were put up.

Two centuries on, we come to Ukrainian writer Hryhory Kvitka (November 29 [O.S. 18] 1778 –August 20 [O.S. 8], 1843), who called himself Osnovyanenko after the village where he was born. Kvitka was primarily a playwright, as he was appointed director of a newly opened theater in Kharkov, but he was also a journalist and penned a History of the Kharkov Theater in 1841. Kvitka was a stout proponent of Ukrainian as a literary language, though he also wrote in Russian. He was a friend of Nikolai Gogol.

The French painter and engraver François Bouchot was born in Paris on this date in 1800. In 1823 he won the Prix de Rome and set off for Italy, where he remained seven years. He was awarded the Legion of Honor in 1835. At the command of Louis-Philippe he created a number of historical paintings, including one on The Battle of Zurich (fought between the French and Austrians in 1799). The Liberian stamp shows Bouchot’s Napoleon Signing His Abdication at Fontainebleau. The artist was married to a daughter of the opera singer Luigi Lablache. After Bouchot’s death on 7 February 1842 Francesca Bouchot married the virtuoso pianist Sigismund Thalberg.

German poet and novelist Wilhelm Hauff (29 November 1802 – 18 November 1827) was rather an interesting figure. He was born in Stuttgart and lost his father at age seven, whereafter he taught himself in the library of his maternal grandfather at Tübingen, later attending that city’s university. After completing a four-year course of philosophy and theology he became tutor to the children of the Württemberg minister of war. It was for these children that Hauff composed his Märchen (fairy tales), some of which, such as “Der kleine Muck” (“The Story of Little Muck”) and “Das kalte Herz” (“The Cold [or Marble] Heart”) remain very popular in German-speaking countries today. The latter story was made into an East German feature film in 1950. (The director, Paul Verhoeven, is not to be confused with the eponymous Dutch director of RoboCop.) Some of Hauff’s poems would also became favorites. His rich imagination also concocted the playful or parodistic The Man in the Moon (1825) and Memoirs of Beelzebub (1826). Also in 1826, under the inspiration of Sir Walter Scott, Hauff wrote Lichtenstein: a Romantic Saga from the History of Württemberg, which not only proved a great hit but also prompted Duke Wilhelm of Urach to reconstruct the castle of Lichtenstein, which had lain in ruins for centuries. A novella, Jud Süß of 1827, is not to be confused with the novel on the same topic by Lion Feuchtwanger. Hauff’s masterpiece is considered to be the novella The Wine-Ghosts of Bremen (Phantasien im Bremer Ratskeller, 1827).

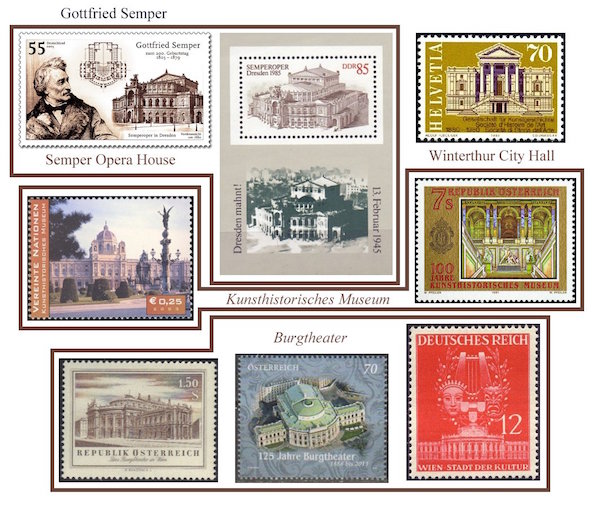

I found so many interesting biographical tidbits about the life and work of German architect Gottfried Semper (29 November 1803 – 15 May 1879) that I’ll beg your pardon in advance for my longwindedness. He came of an affluent industrialist family in the Altona borough of Hamburg. He studied at Göttingen, took up the study of architecture in Munich, and began to practice as a subordinate in Paris in 1826. He was still in the city during the July Revolution of 1830. He traveled to Italy and Greece to examine ancient architecture and took part in archaeological research at the Acropolis. He became a professor of his subject at Dresden in 1834, and there he began his independent creative work. One of his earlier projects was a synagogue, known as the Semper Synagogue, which combined a romanesque exterior with a Moorish Revival interior. Curiously, Semper’s good friend the notoriously anti-semitic Richard Wagner was entranced by a silver lamp Semper had designed for the synagogue and went to great pains to have a copy made. The synagogue, alas, fell victim to the violence of Kristallnacht, when it was burned down by Nazi vandals. Nothing remains but the Semper-designed Star of David, saved from the roof by a fireman and restored to the congregation in 1949. (A New Synagogue, erected on the same location, was completed in 2001.) One of Semper’s other great buildings burned during his own lifetime and was rebuilt in accordance with his design. This was the famous Semper Opera House, built between 1838 and 1841. Fire claimed it in 1869, and Semper’s plans for the replacement, completed in 1878, were realized by his son Manfred. But we get a bit ahead of ourselves. Having been merely an observer of the 1830 revolution, Semper (like Wagner) was actively involved in the succeeding one of 1848-49. A wanted man, he left Dresden never to return, though he was given a broader German amnesty along with other revolutionaries in 1862. An exile in Zurich and London (Semper had a hand in the design of the Duke of Wellington’s funeral carriage), he wrote the important volume The Four Elements of Architecture (1851). He lived mostly in Paris after that, until invited to judge entries for a polytechnical school in Zurich (which he ended up designing himself). While in Switzerland he also built the The City Hall in Winterthur (1865-69), seen on a Swiss stamp of 1980. But magnificent undertakings were still to come. For Vienna he created, in collaboration with Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer, both the Kunsthistorisches Museum (Art History Museum) and its twin Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum) between 1871 and 1891, with the Burgtheater (Imperial Court Theater) seeing completion in 1888. This, too, faced almost total destruction when bombed by the Allies on March 12, 1945, with a subsequent fire the next month worsening the damage. The Burgtheater was restored between 1953 and 1955. As for Semper, he died while on a visit to Italy and is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome.

Icelandic organist Pétur Guðjohnsen (1812 – August 25, 1877) was a teacher of choral singing who worked for many years on a volume of hymns that was published posthumously in 1878. His teaching sparked a revival in the singing life of the nation.

We have another architect of public buildings, this one a Czech named Václav Roštlapil (29 November 1856 – 23 November 1930). From the Prague Technical University he went to Vienna to pursue a course in architecture. Most of his buildings were designed for Prague, typically for scientific and educational institutions. One such was Straka Academy, shown on the stamp issued just this year by the Czech Republic.

Prague was also the site where actress Hana Kvapilová (née Johanna Kubesch, 1860 – 8 April 1907) was born and died. Musically inclined, she taught piano and played in the orchestra of the Provisional Theater. She started acting in 1884 and did well enough to be invited by the dramaturg Pavla Švanda to turn professional. From 1888 to the end of her life she was a member of the National Theater. She came in for some criticism for her progressive views and feminism. Kvapilová died suddenly of hereditary diabetes at the age of 46.

The Greek opera composer Spyridon Samaras (1861 – 7 April 1917) was born on Corfu and studied at the Athens Conservatory. After the première of his first opera in 1879 he went to Paris for further study and became a favorite of Massenet. He also studied with Delibes and Gounod. Following a few years in Paris he moved on to Italy in 1885 and became a significant figure there. In all he wrote some fifteen works for the stage, including operetta, and he provided the anthem for the first modern Olympic Games in 1896. This hymn (not to be confused with the famous Olympic Fanfare by John Williams) has been sung at every Olympic ceremony since the 1960 Winter Olympics.

Polish painter Józef Pankiewicz (29 November 1866 – 4 July 1940) was a student of Wojciech Gerson at the School of Fine Arts in Warsaw, then, on a scholarship, he went to the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. In 1889 he and a fellow painter decided to go to Paris to participate in the Universal Exposition. Pankiewicz won a silver medal for one of his pieces and became enamored of the country and the impressionist art he found there. He would make numerous return visits to France over the years. On his return to Poland in 1890 he tried to expose his countrymen to impressionism but was rebuffed by critics, one of whom suggested he should consult an optometrist. He went his own way, in more ways than one. Besides keeping to the style he believed in, he also traveled a great deal throughout Western Europe, winning another medal at the 1900 Paris Exhibition, a gold one this time, for his portrait Mrs. Oderfeld and her Daughter. Pankiewicz accepted a position at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts in 1906 but continued his excursions to France. During World War I he lived in Spain, there meeting Robert Delaunay, who introduced him to fauvism. After a return to the Kraków Academy in 1923, he was named director of its Paris branch and happily painted still-lifes (one of these is seen on the Polish stamp) and landscapes. The French rewarded him by making him a member of the Legion of Honor in 1927.

Danish composer Jacob Gade (1879 – February 20, 1963) is apparently not related to his 19th-century namesake Niels Wilhelm Gade. The name, I believe, is pronounced more or less like English “gather.” Jacob was a violinist and composer, mostly of light orchestral music. He is remembered today for a single tune, the tango “Jalousie”, written in 1925. The first recording was made by…wait for it…the Boston Pops under Arthur Fiedler in 1935! Frankie Laine sang it for a 1951 recording, and ten years later Billy Fury put out a new version with new lyrics that reached No.2 on the UK singles chart for 1961.

By an odd alignment of the stars, our next two subjects are both Polish stage and film actors. The elder of them was Franciszek Brodniewicz (frahnt-SEE-shek brod-N’YEH-vitch; 29 November 1892 – 17 August 1944). He worked in theater in various Polish cities during and after World War I, ending up in Warsaw. He had started in films in 1922 and switched exclusively to film work in the years leading up to World War II, but refused to appear in any movies made under the auspices of the occupying power. Instead, he worked exclusively at a Warsaw cabaret, augmenting his income by waiting tables until promoted to hall manager. The heroic Brodniewicz also hid a Jewish woman in his apartment and helped a neighbor escape from the Gestapo. He died of a heart attack during the Warsaw Uprising when a bomb exploded outside his apartment building.

One of the films Brodniewicz turned down was the outrageous propaganda vehicle Heimkehr (Homecoming, 1941), which portrayed the Poles as viciously and murderously abusive toward the pre-war German minority. The casting for this film had been the work of pro-Nazi Polish actor Igo Sym, who plays a role in the life of our next Polish actor, Elżbieta Barszczewska-Wyrzykowska (elzh-B’YAY-ta barsh-TCHEFF-ska vizh-i-KOFF-ska). Born on November 29, 1913, she made her stage debut in 1934 playing Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. In the succeeding years before the war she played leading roles in thirteen films as well as continuing her work on the stage. Like Franciszek Brodniewicz she waited tables during the war, also working in underground theater, but she was arrested by the Gestapo as a possible conspirator in the murder of our old friend Igo Sym, who had been assassinated by the underground on March 7, 1941. I wasn’t able to learn whether she was released or held captive until war’s end (21 hostages were murdered by the Germans in retaliation for Sym’s assassination). (Incidentally, I found that Sym had acted opposite Jerzy Pichelski, whose stamp we just saw a few days ago, in a 1933 picture.) In any case, Barszczewska resumed working on stage after the war at the Polish and National Theaters and took part in only one more film in 1977. She died ten years later, on October 14, 1987, aged 73.

The Danish director Erik Balling (29 November 1924 – 19 November 2005) created two of the most popular Danish television series, The House in Christianshavn (comedy, 1970-77) and Matador (drama, 1978-82). He also directed the first fourteen of the fifteen films in a comic series featuring The Olsen Gang (1968-81), and he wrote the script for the last one. Balling’s directorial debut was with Adam & Eva (1953), which was nominated for Denmark’s Bodil Award for best film. In 1956 he directed Kispus, the first Danish feature to be filmed in color.

Austrian painter, sculptor, and graphic artist Gottfried Kumpf turns 87 today (born 29 November 1930). He gets a mention here on account of the various postage stamps he has designed for Austria and the United Nations, but first I’d like to draw your attention to the elephant sculpture he made that sits outside Gottfried Semper’s Natural History Museum in Vienna. Most of his paintings are landscapes executed in a naïve style, as can be seen on the Austrian stamp of his Evening Sun in Burgenland (where the artist has lived since 1968), as well as on the UN stamp celebrating International Youth Year in 1995. For more, see his website.

An important member of Duke Ellington’s circle, composer, pianist, lyricist, and arranger Billy Strayhorn (November 29, 1915 – May 31, 1967), lacks a stamp.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.

Do you know much about the ancestry of Hans Holbein? I have many Holbein ancestors from Hessigheim and Kilchberg Tübingen .

I have an old stamp album my father gave me.