The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 10

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

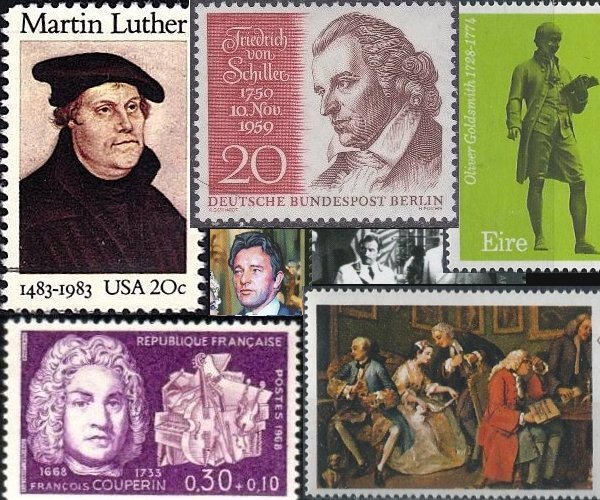

We have some very famous names today, in fact, the well-known figures in today’s lineup outnumber the less familiar ones (7 to 6). November 10 brings us Martin Luther, Friedrich von Schiller, François Couperin, William Hogarth, Oliver Goldsmith, and actors Richard Burton and Claude Rains. And our other talents come from Russia (a lexicographer), Argentina and Ireland (poets), Poland (prose writer), and Slovenia and Slovakia (painters). It’s also the 155th anniversary of the first performance of Verdi’s La forza del destino.

Besides upsetting the theological apple cart (and nailing 95 worms to the door), Martin Luther (1483 – 18 February 1546) was, of course, a prolific writer of hymns, “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” being one of the best loved, and these served as the basis for later compositions by others, notably Bach, who used several of Luther’s melodies in his cantatas. The stamps, as you might expect, really commemorate Luther as the founder of the Protestant Church and not as a composer. Most of his stamps, predictably, come from Germany (as is the case with Schiller), but there’s one (at upper right) from the US (which rarely honors foreigners philatelically, but in this case, y’know, we made a very special dispensation for reasons having something to do with, I dunno, the true holy fount of American greatness and exceptionalism, maybe), and, perhaps surprisingly, there is also one from Catholic Brazil.

Friedrich von Schiller (1759 – 9 May 1805) provided (unwittingly) not only the text for the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth, but the inspiration for a great many other composers. Schubert was especially fond of setting Schiller’s verses (more than 30 songs!), and Schumann, Brahms, Liszt, and Richard Strauss all wrote songs to Schiller poems. Schumann also wrote a Bride of Messina Overture, Brahms a choral setting of “Nänie”, and Liszt a symphonic poem (#12) on “Die Ideale“. The plays also were a rich source for opera: Rossini’s William Tell, Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda, and Tchaikovsky’s Maid of Orléans are all derived from Schiller’s plays. Verdi so admired Schiller’s dramas that he based no fewer than five (!) operas on them: I masnadieri (after The Robbers), Giovanna d’Arco (The Maid of Orleans), Luisa Miller (Intrigue and Love), Don Carlos, and La forza del destino (based partly on Wallenstein), which had its première on this date! Wallenstein also served as the inspiration for the eponymous tone poem by Smetana and symphonic trilogy by Vincent d’Indy. All of the stamps come from Germany (though two of them were issued under Allied occupation) except for the one from the Soviet Union.

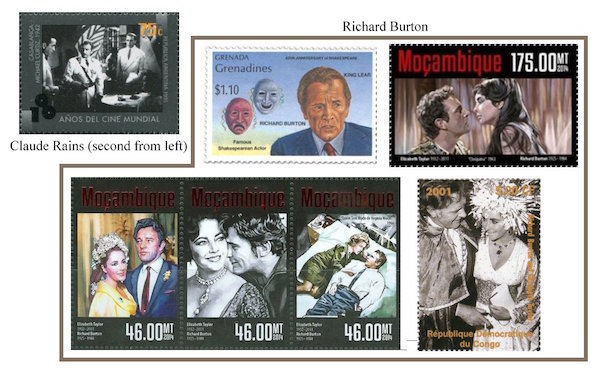

You’d never guess from his generally pleasant demeanor that English actor Claude Rains (10 November 1889 – 30 May 1967) was a child of wretched poverty. Nine of his siblings died in infancy of malnutrition, and little Claude suffered from a speech impediment. You’d also never guess that he grew up with an impenetrable Cockney accent. His father was a stage actor, and Claude did back stage chores leading to small roles. In World War I he apparently served in the same regiment as Basil Rathbone, Ronald Colman, and Herbert Marshall. Rains rose from private to captain. After the war, no less a figure than Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree paid for elocution lessons so that Rains could shed his impediment and accent. His career rose quickly thereafter. In the late 20s he appeared on Broadway, and his first film role (after a single British silent of 1920) was the lead in The Invisible Man (1933). Rains was nominated for a supporting actor Academy Award for his role in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939), and he became a naturalized US citizen in that year. He won a Tony for Darkness at Noon in 1951. He was married six times, his fifth wife being the classical pianist Agi Jambor. Shame on you if you don’t recognize the scene depicted on the stamp!

Alas, Rains was a chronic alcoholic, and so, of course, was Richard Burton (10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984). Many people believe that this affliction prevented him from fulfilling his promise as the successor to Olivier. There are other parallels with Rains: Burton was born into a large family of thirteen, he married five times (twice to Elizabeth Taylor), and he never won an Oscar despite being nominated seven times. He was born in Wales as Richard Walter Jenkins Jr. and took the name Burton from an admired mentor. Apart from the stamp issued by Grenada, Burton shares stamp space with Taylor, and it gives me no end of pleasure to see that one of the stamps uses a still from the unforgettable Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

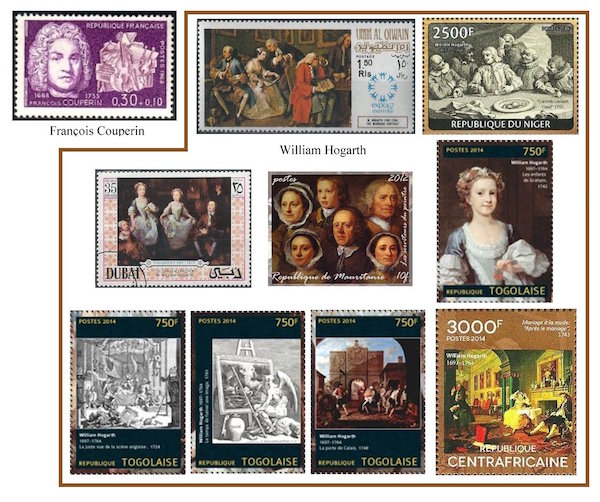

French composer François Couperin “le Grand” (1668 – 11 September 1733), the most famous member of a large musical family of the 17th and 18th centuries, was the composer of 27 suites of harpsichord pieces, two organ masses, and a variety of chamber and sacred works.

William Hogarth (10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was a Londoner who began his career in engraving. One of his earliest efforts was a satirical print mocking the victims of the South Sea Bubble, a starting point for such later series as A Harlot’s Progress (1731), A Rake’s Progress (1733-35), and Marriage à-la-mode (1743-45). The opening piece from the last-named series, The Marriage Contract, is seen on a postage stamp from Umm al Qiwain. Hogarth also painted portraits and historical and biblical scenes and wrote a book, The Analysis of Beauty (1753). One engraving from that volume is called Columbus Breaking the Egg (on the stamp from Niger). The only examples of Hogarth’s portraiture on stamps are one from Mauritania showing Hogarth’s Servants (mid-1750s) and one from Dubai offering The Graham Children (1742), with the eldest daughter also appearing on a stamp from Togo. In the bottom row we see the other Togolese stamps from the same issue: two prints, A Just View of the British Stage (1724) and Time Smoking a Picture (1761), and the painting The Gate of Calais (also known as O the Roast Beef of Old England, 1749). We hear a report about this picture from Horace Walpole, no less: “he went to France, and was so imprudent as to be taking a sketch of the drawbridge at Calais. He was seized and carried to the governor, where he was forced to prove his vocation by producing several caricatures of the French…They were much diverted with his drawings, and dismissed him.” We close with the second image from the Marriage à-la-mode series, After the Marriage.

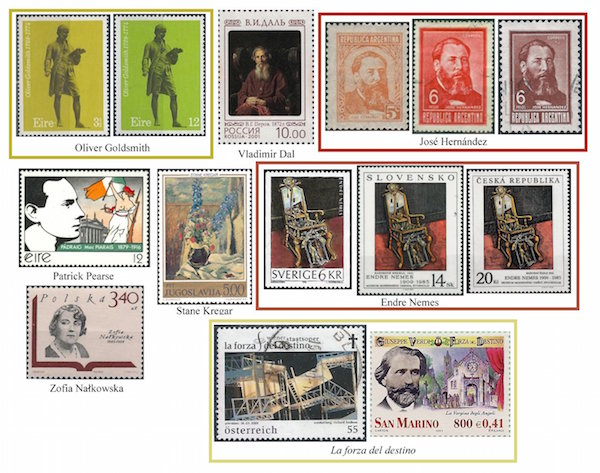

Another keen observer of the London scene was Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774), novelist, playwright, poet, and friend of Samuel Johnson. The authority for his date of birth is Goldsmith himself, and there is no confirming record. Even his place of birth in Ireland is contested. He attended Trinity College, Dublin but performed poorly and led a footloose and unsettled existence for some years. He came to London in 1756 and supported himself (and his gambling habit) with hack writing and other jobs until some of his more careful compositions caught the eye of Dr. Johnson. Again we have a quotation from Horace Walpole, who called Goldsmith an “inspired idiot” for his literary creations and his dissolute lifestyle. The greatness of four of Goldsmiths’ works is undeniable: the novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), the pastoral poem The Deserted Village (1770), and the plays The Good-Natur’d Man (1768) and She Stoops to Conquer (1771, first performed in 1773).

I find the Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dal (November 10, 1801 – September 22, 1872) most interesting not only for his accomplishments but for his associations. Both of his parents were linguists, his father, a Dane named Dahl, knowing eight languages and his mother, of German and French Huguenot ancestry, at least five. Dal himself could claim six. He was also fascinated with folklore and collected and published folk tales and proverbs from his native Novorossiya on the Black Sea. Unable to devote more time to this pursuit, he asked Alexander Afanasyev to edit the material, and the result was one of the great fairy tale collections, rivaling that of the Brothers Grimm. That’s one “most interesting” association. Another was that some of the unpublished tales were taken up by his friend Alexander Pushkin and set in verse. (Dal also sat by the great poet’s deathbed in the final hours of his life.) Dal’s magnum opus, though, was his Explanatory Dictionary of the Live Great Russian Language (1863-66). Several years later, he completed another vast project, The Sayings and Bywords of the Russian People, consisting of more than 30,000 entries. Two other interesting connections, albeit posthumous, are worth mentioning, I think. During his student years at Cambridge, Vladimir Nabokov acquired a copy of the dictionary and loved poring through its pages, and when Alexander Solzhenitsyn was sent to the gulag, the one book he took with him was a volume of Dal.

The Argentine journalist and poet José Hernández (November 10, 1834 – October 21, 1886) was also of mixed ancestry, Spanish, Irish, and French. He was also a soldier and politician and founded a newspaper. His best known work is the epic poem Martín Fierro, published in two parts in 1872 and 1879. His Wikipedia article describes this as “the pinnacle of gauchesque literature.”

If political thinking was a large part of Hernández’s life, it was central to that of the Irish nationalist Patrick Pearse (Irish: Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916). The street in Dublin where he was born is named for him today. His father was a mason and sculptor with a love for books. A fervent patriot from his early years, Patrick earned his degree in modern languages and devoted himself to the preservation of Irish, founding a school to that end. Pearse himself wrote poetry and stories in both Irish and English and plays in Irish. His political writing was of such importance that he was seen by many as the voice of Irish Nationalism. He was a leader of the Easter Uprising of 1916 and was one of the fifteen executed in its aftermath.

The Polish novelist Zofia Nałkowska (10 November 1884 – 17 December 1954) came of a family of intellectuals and progressives and was educated in what was known as the Flying University, a clandestine operation hidden from the prying eyes of the administrators of the Russian Empire. Thus from earliest youth encouraged to challenge authority, Nałkowska took on controversial topics, particularly focusing on women’s issues. Her first book, in fact, was called Women (Kobiety, 1906), but she wrote another half-dozen books before having a success with The Romance of Teresa Hennert (1923). She also composed three stage plays and many essays and was an executive member of the Polish Academy of Literature from 1933 to 1939. As for eroticism in fiction, she declared: “It has its ramifications within all domains of human life and…it cannot be isolated by prudery or relegated to science for its purely biological dimension.”

Our next artist was also a Slav, the Slovenian painter Stane Kregar (November 10, 1905 – August 1, 1973). He studied theology and was consecrated as a priest in 1929. In the next year, he went to Prague to study at the Academy of Fine Arts and became an adherent of the modernist and Cubist schools, though most of what I see online is strongly representational. He taught drawing at Ljubljana from 1935 and gave an exhibition of his own art the following year. His work became more abstract around 1950. Not surprisingly, it is centered on religious art, altar paintings, frescoes, mosaics, stained glass windows, even liturgical vestments. An exception to the rule is the still life shown on the Yugoslav stamp of 1974. A change in Kregar’s style can be seen by comparing Pilgrims (Romarji, 1939) with Boats on the Coast (Čolni na obali, 1957).

Endre Nemes (NEH-mesh, November 10, 1909 – September 22, 1985), meanwhile, went in for Surrealism. He was born Endre Nágel in Hungary, grew up in what today is Slovakia, studied in Vienna, changed his name to Nemes, and fled the Holocaust for Sweden (ultimately), where had his first solo exhibition in 1941 and where he chose to make his home, obtaining citizenship in 1948. His busy canvases often portray mannequins, harlequins, and clocks or other detailed mechanical devices as in The Baroque Chair of 1941 (which inadvertently anticipates George R. R. Martin’s Iron Throne, does it not?). Although dual issues from different countries are not unusual, this case offers three nearly identical stamps released on the same day by three different countries in 1996: Sweden, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. Nemes worked in a variety of media and genres including tapestry and mural and added ceramics to his paintings.

Finally, it was on 10 November 1862 that Verdi’s masterpiece La forza del destino had its première in, of all places, Saint Petersburg, where it was given at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater. The final revision, with the now-famous new overture, was first produced at La Scala on 27 February 1869.

I’m shocked that there’s no stamp for American-British sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 19 August 1959), and Italian composer Ennio Morricone (born 10 November 1928) is also on the waiting list.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.