The Arts on Stamps of the World — November 1

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

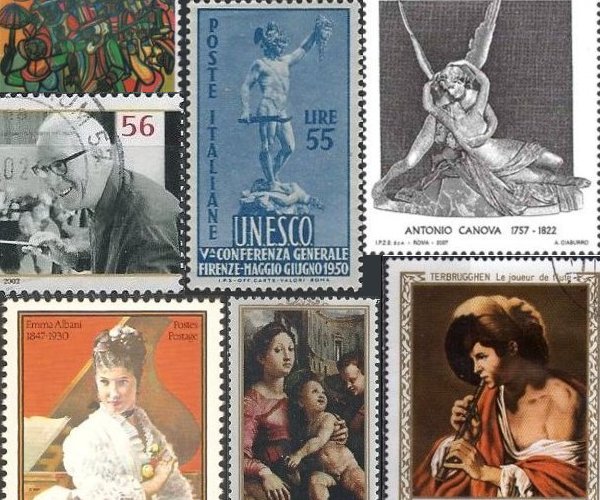

Painters rule the roost today, and we have them aplenty, a swelling baker’s dozen, if you can believe it. We begin with three Italian artists of the 16th and 17th centuries—Benvenuto Cellini leads the pack—and add an 18th-century one, the great sculptor Antonio Canova (also one of the painters), a bit later. Other highlights today are Dutch painter Hendrick ter Brugghen and German conductor Eugen Jochum, and we note the first performances of two Shakespeare plays.

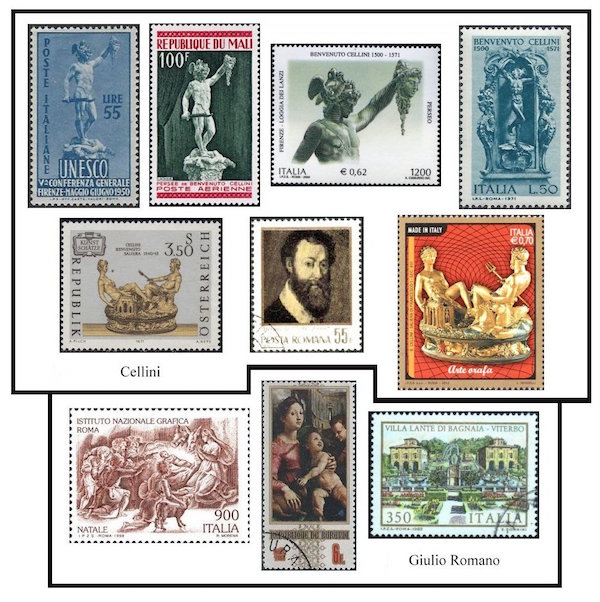

Benvenuto Cellini (1 November 1500 – 13 February 1571) was a goldsmith, sculptor, draftsman, soldier, musician, rogue, and braggart and the author of a “legendary” autobiography as well as some poetry. He was a Florentine, born to a musician and instrument builder, which is how Cellini got his start in music as a flute player. He was apprenticed, though, to a goldsmith, first in Florence, then in Siena, where he ended up after being banished from his hometown for some teenaged hell-raising. When he was 19 he moved to Rome and fashioned some pieces in silver that caught the eye of Pope Clement VII. Later a certain boy caught Cellini’s eye, and he was fined for sodomy. The year 1527 brought the infamous sack of Rome, in which Cellini claimed to have fired the shot that killed the commander of the besieging forces, Charles III, Duke of Bourbon. Whether that was true or not, it seems he did distinguish himself to the extent that Florence declared all forgiven and invited him back. A mere two years later, Cellini murdered a man who had killed Cellini’s brother in self-defense and had to skedaddle again, this time to Naples. Pardoned for that killing, he committed another soon afterward, and then one or two more. While at the court of French King Francis I a woman accused him of…sodomy. And so it went. Yet when Cellini died he was buried with great ceremony. Which brings us to his greatness as an artist and, at last, to our stamps. Perhaps the finest of his works is the magnificent Perseus with the Head of Medusa made between 1545 and 1554. It’s on two stamps of Italy, one from the year 1950, one from 2000, with a Malian issue in the middle. (We have another great Perseus, the one by Canova, further down the page.) Dating from the same period is Cellini’s Mercury, also on an Italian stamp, this one from 1971. In the next row are two stamps devoted to the gorgeous saltcellar made in Paris in the early 1540s. Between these stamps of Austria and Italy (the latter quite recent, from 2013) is a portrait of unknown provenance (that is, unknown to me). And let us not forget the masterpiece by Berlioz, an entire opera based on the rapscallion’s adventures.

Painter and architect Giulio Romano comes second despite having been born just a bit earlier, probably, than Cellini, some time around 1499. He died on this date in 1546. Originally named Pippi, his birthplace of Rome determined the name by which he became known. Romano was one of Raphael’s students and after the master’s death helped complete projects Raphael had left undone. He moved at the request of Federico Gonzaga to Mantua, and remained there from 1524 to the end of his life. Romano took over a number of restorations, designed a Church of San Benedetto, and opened a successful studio. Like Cellini, he also went to the France of Francis I. Although Romano was rather more important as an architect than as a painter, two of the three stamps show a drawing and a painting. The drawing is an Adoration of the Shepherds (Romano also painted this subject at least once, around 1535), and the painting is a Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist. The third stamp shows one of his architectural treasures, the Villa Lante al Gianicolo (1520-21), shown here from the loggia side. Another building I’d like to show you is the first one he built for Mantua, the Palazzo del Te (1524-34). It houses an extraordinary fresco, also by Romano, The Fall of the Giants, so remarkable for the verisimilitude of its illusory dome, from which the giants really do appear to be tumbling right into the room. Giulio Romano may be less well known than Cellini, but he has one laurel his contemporary lacks: he is the only Renaissance artist mentioned in a Shakespeare play. In Winter’s Tale, V, ii, Queen Hermione’s statue is said to have been made by “that rare Italian master, Julio Romano,” despite the fact that Romano was not a sculptor. (He did also design tapestries, though.)

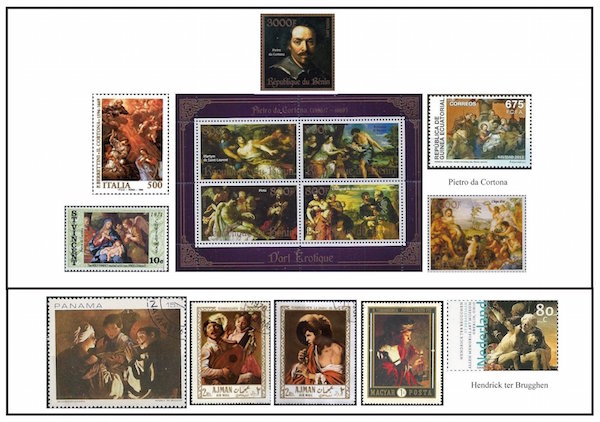

Pietro da Cortona (1 November 1596 or 1597 – 16 May 1669) was also both a painter and an architect. In his case, the painting tended to come earlier in his career, the architecture later on. Like Romano, his name, originally Berrettini, derives from his birthplace. From a family of artisans in Tuscany, he did most of his work in Rome and Florence. Another parallel with Romano is Cortona’s grand ceiling fresco, The Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power, another tour de force that tricks the eye by suggesting the open sky with figures within the building and others apparently elevated above it. On the stamps we see a Self-Portrait above the Beninese souvenir sheet, which contains, clockwise from upper left, The Martyrdom of St Lawrence, Romulus and Remus Given Shelter by Faustulus (c1643), The Alliance of Jacob and Laban (1630-35), and a Pietà (1620-25). Outside the sheet at upper left is an Annunciation, beneath it a detail from Holy Family with Two Angels. At the top on the other side is The Age of Gold, one of a group of frescoes representing the four ages of man that was commissioned by one of the Medici for the Palazzo Pitti in 1637. (Cortona completed the Bronze Age and Iron Age frescoes in 1641.) For the same palace Cortona also began a series of mythological/cosmological frescoes on the gods/planets. (These were completed by his pupil Ciro Ferri in the 1660s.) To wrap up, here are links to two examples of Cortona’s architectural work, the Church of San Luca e Martina and the façade for Santa Maria della Pace, both in Rome.

We keep to painting but move north to the Netherlands, although Hendrick ter Brugghen (or Terbrugghen, 1588 – 1 November 1629) was one of the Dutch followers of Caravaggio–the so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti. Luckily for me, very little is known of his life. He was born, actually, at The Hague, but his father was a secretary at the Court of Utrecht, serving William the Silent. We do know that ter Brugghen spent some years in Rome, stopped at Milan in 1614 on his way home, and once back at Utrecht, got married and worked with Gerard van Honthorst (whose birthday is three days away) until his death at the age of 42, possibly as a result of the plague. One of ter Bruggen’s works, The Concert (1627), comes from the same Panamanian stamp set we featured yesterday with Vermeer’s Lady Seated at a Virginal. Two other musical paintings are The Duet (1628) and The Flute Player (1621). (Another Flute Player by ter Brugghen dates from about 1624.). We see the politically incorrect Boy with Pipe (1623) on a stamp from Hungary and a detail from St Sebastian Tended by Irene and her Maid (1625) on one from the Netherlands.

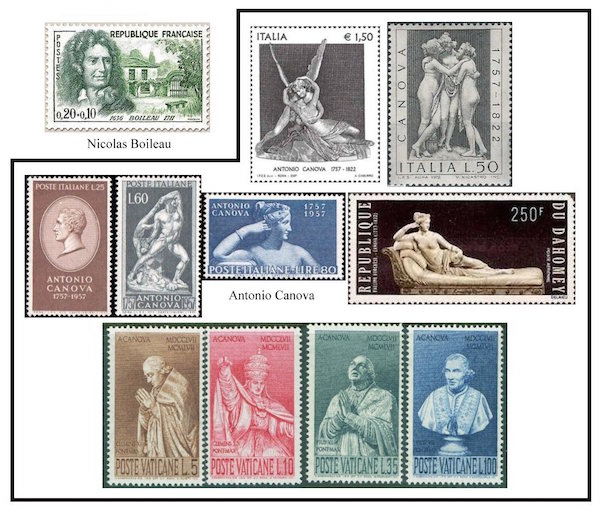

Now we leave the visual arts, just for a moment, to visit with French poet and critic Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux (1 November 1636 – 13 March 1711). His father, too, was an official at court, a clerk in the parliament, and Nicolas was his fifteenth child. Boileau is known for his twelve poetical satires, modelled on Juvenal, and The Art of Poetry (L’Art poétique, 1674), written in imitation of the Ars Poetica of Horace).

And we bounce back to the visual arts—and to Italy—for the great sculptor Antonio Canova (1 November 1757 – 13 October 1822). One of his most striking creations is not on a stamp, so I thought we’d get a running start with it: Theseus and the Centaur (1805-19). Rather like Pietro da Cortona, whose father was a mason, Canova’s was a stonecutter, and after his father’s death in 1761, Canova was brought up by his grandfather, also a stonemason; he owned a quarry and was a sculptor who made statuary and low reliefs for altars. Canova’s rise was rapid. In 1779, he opened his own studio. He took no pupils, but was extremely generous to young or struggling artists. In later years he was famous throughout Europe, and his reputation spread beyond the Atlantic, as he was asked to make a statue of George Washington for North Carolina in 1820. Two of his most beautiful creations are Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787) and Three Graces (1813-16). Earlier Italian stamps (from 1957) show a medallion of Canova’s profile (a self-portrait?), Hercules & Lychas, and a detail from Venus Victrix (1805-08). The complete sculpture is seen on a stamp from Dahomey. Certainly Canova did execute a self-portrait, this one on canvas, in 1792. In the final row, on stamps from the Vatican, we have four portraits, some of them cenotaphs, of popes: Clement XIII for St. Peter’s Basilica, Clement XIV, Pius VI, and Pius VII. I mentioned above in the paragraph on Cellini that there was also a Perseus by Canova (c1800), not on a stamp, but here it is, and it’s a splendid one.

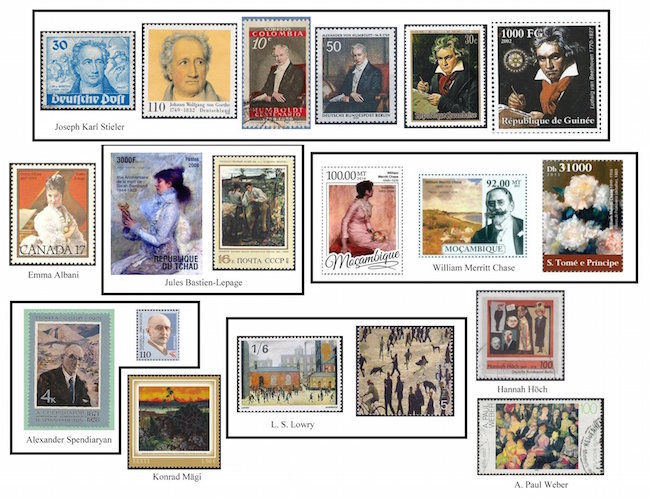

Yet another painter is next, this one from Germany, less famous in his own right than for his sitters, who included King Ludwig I of Bavaria (1826) and his mistress Lola Montez (1847), Goethe (1828), Alexander von Humboldt (1843), and Beethoven (1820), in what is probably the most famous likeness of the great composer. The last three portraits have all been used, more than once, on postage stamps of the world. The artist? Joseph Karl Stieler (1 November 1781 – 9 April 1858), painter at the Bavarian court from 1820 to 1855. He came from a Mainz family of engravers and started out painting miniatures. He was already past thirty when he went to the Academy of Fine Arts at Vienna. Here is his Self-Portrait of 1806. His son Karl (1842–1885) was a well known writer after Stieler’s death.

Soprano Emma Albani (1847– – 3 April 1930) was the first Canadian opera singer to achieve international recognition. She was born Marie-Louise-Emma-Cécile Lajeunesse. After spending some time in New York state, she went to Paris and Italy, where she changed her name to Emma Albani and scored a number of successes in various cities. She then went to Covent Garden, where she made her debut in the spring of 1872 in La sonnambula. She performed before Tsar Alexander II in St. Petersburg, Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, and Kaiser Wilhelm I at Berlin. Her first tour of the US took place in 1874, but she didn’t perform opera in Canada until 1883, when she sang in Lucia di Lammermoor in Toronto. She appeared at the Met in 1891 and 1892. Her retirement from the stage came in 1911, and she and her husband lived the rest of their lives in London. The stamp issued on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of her death is one of the very few Canadian stamps to honor classical musicians.

Don’t look now, but we have another painter. Jules Bastien-Lepage (1 November 1848 – 10 December 1884), son of a painter, was indulged by his not especially affluent parents, who would buy prints for him to copy. Jules studied at Verdun and at Paris (again the École des Beaux-arts). He was a soldier in the Franco-Prussian war and resumed painting while recovering from his wounds. An 1874 portrait of his grandfather received rave reviews. He was in Italy between 1880 and 1883 and hoped to regain his health in Algiers, but he fell victim to cancer at the age of 36. One of the two paintings we have on stamps we saw just recently, Bastien-Lepage’s Portrait of Mlle Sarah Bernhardt (1879), which earned him the Legion of Honor in 1874. The other picture we have, on a Russian stamp, is L’Amour au Village (Young Love, 1882).

Did I mention we have a lot of painters today? The American William Merritt Chase (November 1, 1849 – October 25, 1916) came from Indiana. At 20 he went to New York and studied with a student of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Facing financial difficulties, he joined his family in St. Louis, Missouri, where wealthy collectors arranged for him to visit Europe for two years, in return for which Chase would provide his own paintings and acquire European ones for their collections. Chase studied in Munich and came back to the US in 1878 to open a studio in New York. This was Albert Bierstadt‘s old studio on Tenth Street, which Chase turned into a lavish repository of exotica that in the end he couldn’t maintain. He had to auction everything off in 1895. In the meantime, though, he had opened in 1891 a summer school on Long Island, where he taught until 1902. His many students included George Bellows, Charles Demuth (birthday one week from today), Joseph Stella, and Georgia O’Keeffe (birthday two weeks from today). Chase is probably best known for his portraits and representations of his wife and children, still lifes, and, from the late 1880s, landscapes. We have three stamps: from Mozambique Surprise (1883-84) and Idle Hours (c1894) and from São Tomé a small detail from Spring Flowers (Peonies). I also found online his Portrait of Miss Dora Wheeler, which has a most eye-catching color scheme.

Armenian composer and conductor Alexander Spendiaryan (known in Russia as Spendiarov; 1871– May 7, 1928) is held to be the founder of Armenian symphonic music. He studied with Rimsky-Korsakov and won the Glinka Prize three times, the first time with his symphonic poem “Three Palms” in 1908. His other well known works include the opera Almast (1923) and the Yerevan Etudes (or Yerevan Sketches; 1925). Aram Khachaturian said of him, “I am profoundly convinced that Spendiarov and Komitas are the patriarchs of Armenian classical music.” The USSR honored him with a stamp in 1971, his centenary year. I have also included a tiny image, the best I could find online, of an Armenian issue from 2000.

Now, I know we mustn’t stray too far from painters today, so we have four more in a row for you. Meet and greet the Estonian Konrad Mägi (1 November 1878 – 15 August 1925), who produced mainly landscapes. His pieces are considered to be among the first modern Estonian nature paintings. Mägi studied at Tartu from 1899-1902, in Saint Petersburg (1903-05), and in Paris (1907). He lived in Norway from 1908 to 1910. Back at home in 1912, he worked as an art teacher. On the stamp we can see his Landscape with a Red Cloud (1913-14). Two other examples of his interesting work are Portrait of a Woman (c1910) and Venice (1922-23).

The Englishman L(aurence) S(tephen) Lowry (1 November 1887 – 23 February 1976) had a penchant—if not an obsession—for painting bustling crowds of people in urban or industrial landscapes. Most of these he executed in his native Lancashire and environs, where he lived for forty years. The UK has issued two postage stamps showing his work. The first is of Coming Out of School (1927). The other celebrates The Lowry, a gallery of his work in the city of Salford in Manchester, but I can’t name the picture. For the L. S. Lowry Centenary Festival, a ballet was commissioned from the Northern Ballet Theatre by the City of Salford and the BBC. A Simple Man, with choreography and direction by Gillian Lynne and music by Carl Davis, featured dancers Christopher Gable and Moira Shearer (in her final dance role).

German Dada artist Hannah Höch (November 1, 1889 – May 31, 1978) is celebrated for photomontage, which she and her lover Raoul Hausmann practically invented. Höch was born at Gotha and attended the School of Applied Arts in Berlin from 1912, interrupting her studies to work with the Red Cross for the first months of World War I. Her difficult relationship with Hausmann lasted from 1915 to 1922, but she made friends with a number of other important artists, such as Kurt Schwitters and Piet Mondrian. Her works were declared “degenerate ” by the Nazis, but she remained in Germany and lived quietly through the war years. Again, I was not able to identify the piece on the stamp.

Another German artist, a lithographer, engraver, and, yes, painter, was A(ndreas) Paul Weber (1893 – 9 November 1980). As a member of the back-to-nature hiking group Jung-Wandervogel (Young Wandering Birds), he crisscrossed much of Germany on foot. During his time on the Eastern Front in World War I he made engravings and caricatures for his corps’s newsletter. He continued in this line of work between the wars, regrettably finding grist for his satirical mill in consistent antisemitism, but at the same time the National Socialists were his target—he contributed illustrations to the book Hitler—A German Misfortune (1932). As a result of this and other criticisms he spent the latter half of 1937 in prison. In 1944, at the age of 50, he was called up for war service. After the war he practiced his art as a book illustrator and painter until his demise eight days after his 87th birthday. His personal antisemitism notwithstanding, Weber is sufficiently well regarded to have had a museum opened in the town of Ratzeburg in 1973 and a stamp showing his painting Audience issued in 1993.

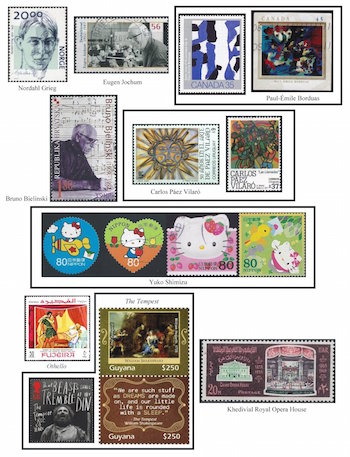

Yes, the Norwegian writer Nordahl Grieg (1 November 1902 – 2 December 1943) was related to the composer, albeit distantly. Born in Bergen, like his namesake, Grieg went to university at Oslo and Oxford, where he wrote a poem called “The Chapel in Wadham College” (“Kapellet i Wadham College“). Grieg had already had a volume of poetry about his experiences as a sailor published in 1922, and another followed in 1924. Three years later he was in China as a journalist, and in that same year two of his plays were produced. Moved by the plight of the poor, he joined the Communist Party and even lived in the USSR from 1933 to 1935. His enthusiasm for the cause led him to write a novel in defense of the Stalinist purges. He started a magazine, but his rather strident support for Uncle Joe alienated his contributors, both literary and financial, and the enterprise lasted only a year or so. In that year, 1937, he wrote two more plays, one about the Paris Commune and the other about the Spanish Civil War. You get the idea. Only after the Nazi-Soviet Pact and the German invasion of Norway did Grieg begin to find fault with Stalin. He served with the Norwegian army, then fled to the UK on the same ship that carried the royal family. As a war correspondent, Grieg flew with air missions, and it was on one of these that he was shot down over Berlin. His friend Graham Greene wrote about him in his autobiographical book Ways of Escape.

Eugen Jochum (1902– 26 March 1987) was one of the most highly regarded German conductors and the father of the distinguished pianist and NEC teacher Veronica Jochum, one of whose students was (is) our dear friend Cathy Fuller of WGBH and WCRB. Eugen Jochum’s brothers Otto and Georg Ludwig were also conductors. He made his debut in Munich in 1926 and was named music director of the Berlin Radio Orchestra in 1932, moving on in 1934 to Hamburg. Because that city remained, to quote Jochum, “reasonably liberal”, he was able to conduct music by Hindemith and Bartók, which was elsewhere banned by the Nazis. In 1949, he became the first music director of the newly-founded Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, where he remained until 1961. He left a large number of superb recordings, his idiomatic and finely judged Haydn “London” Symphony set being among my particular favorites.

Today’s last painter—oh, no, wait there’s one more to come—is Paul-Émile Borduas (November 1, 1905 – February 22, 1960) of Québec. He left school at 12 but at 16 was taken on as an apprentice by Ozias Leduc and resumed his education, which included a spell in Paris in 1929-30. Before and after this he worked as an art teacher. His first abstract paintings were executed in 1941. Later in that decade his criticisms of the Catholic Church made it difficult for him to find work. He moved to New York in 1953 and to Paris in 1955, where he died of a heart attack five years later. Canada has issued two stamps showing his work: Untitled No.6 and Joie lacustre (Joy of the Lake).

The Croatian-Jewish composer Bruno Bjelinski was born Bruno Weiss in 1909. According to English-language Wikipedia, he was interned in a concentration camp, but escaped in 1943 and joined the partisans. (I can find no mention of this on the Wiki pages in other languages, the Croatian version, the most extensive article, saying merely that he “escaped from Zagreb in the Italian zone” and spent the rest of the war on the island of Vis.) He wrote five symphonies after the war and a further nine in his later years, along with many concertos for various instruments. Several of his works for the stage (operas, puppet operas, ballets) were written for children, including versions of The Jungle Book, Pinocchio, Peter Pan, and The Ugly Duckling. He died on 3 September 1992.

The multitalented Uruguayan artist Carlos Páez Vilaró (1 November 1923 – 24 February 2014), who really is our final painter today, also worked as a sculptor, a writer, and a composer, among other things. Born in Montevideo, he moved to Buenos Aires in 1939 and worked as a printer’s apprentice. On his return to Montevideo in the late 1940s, he became interested in Afro-Uruguayan culture and explored numerous artistic avenues in the succeeding years. As a composer he wrote a considerable number of dances in the genres of Candombé and Comparsa and led an orchestra in their performances, some of the instruments being decorated with his drawings. Further studies took him to Brazil and Senegal, and in Paris in 1956 Páez Vilaró was invited to present an exhibit at the Modern Art Museum. While in the city he made friends with Brigitte Bardot and Pablo Picasso. He painted a huge mural for the Pan American Union building in Washington, DC in 1959. Many other murals were created for many countries: Argentina (12), Brazil (16), four each in Chad and Gabon, the United States (11), and no fewer than thirty in his native Uruguay. Not content with all of this, in 1967 Páez Vilaró founded a film production company! As a matter of interest, it should be mentioned that one of his children was among the survivors of the famous Andes plane crash recounted in the 1993 feature film Alive.

We wish a happy birthday to the Japanese designer Yuko Shimizu (born 1 November 1946), the creator of—wait for it—Hello Kitty. The Japanese have an inordinate love of cartoons, if postage stamps are any indication. There seem to be hundreds of them, and no small number featuring Shimizu’s 1974 creation. Apparently the popularity brought her little remuneration. She continues to work as a freelance designer and has also published some picture books.

As mentioned at the outset, two Shakespeare plays, and two of the greatest, had their premières on a November 1st, Othello in 1604 and The Tempest in 1611, both at Whitehall Palace. Stamps exist for both, as you can see.

For the opening of the Khedivial Royal Opera House in Cairo, built on the order of the Khedive Ismail to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal, Verdi’s Aida was the planned inaugural opera, but because of the Franco-Prussian War the sets and costumes could not be shipped from Paris in time, and Rigoletto was given instead. This was on 1 November 1869. Aida received its world première in the same house two years later, on 24 December 1871. Almost exactly one century after that, on 28 October 1971, the hall was destroyed by fire. It was replaced by the new Cairo Opera House in 1988.

And another wag of the finger at the USPS for neglecting Red Badge of Courage author Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.