The Arts on Stamps of the World —October 25

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

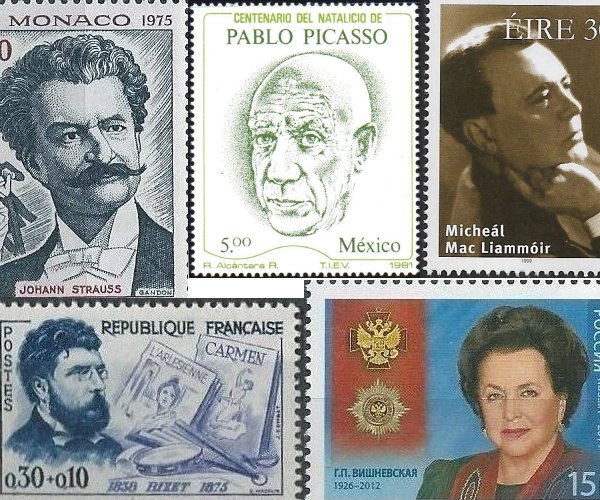

It’s Picasso’s birthday. Not content with that, the Natal Fates preordained to share the birthday blessings with Johann Strauss Jr and Georges Bizet. And for the icing on the (non-birthday) cake, Geoffrey Chaucer may have died on this date 617 years ago.

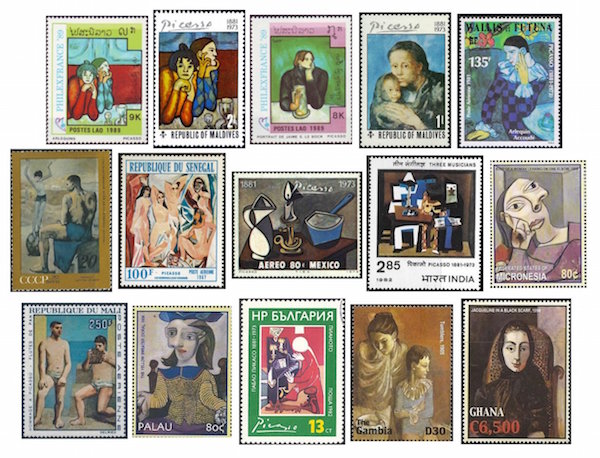

My highly unscientific independent survey concludes that Pablo Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) wins the prize for most stamps by any artist of all the arts. In preparing my Picasso collage for your edification and diversion I’ve had to omit literally dozens of stamps. By careful winnowing (in truth, by entirely arbitrary selection predicated solely on what I liked best and what fits most aesthetically into the assemblage), I have managed to limit the presentation to thirty items. I thought to begin with stamps showing the artist himself, and the first of those is a very early self-portrait, executed in 1896, when Picasso was a mere 15 years of age, a fetching lad with tousled hair. The stamp is Bulgarian and is followed by another self-portrait from ten years later, 1906, on stamps of Monaco and Spain. In the second row are images of the artist that are not drawn from self-portraits, these on stamps from Poland, Monaco, Mali, and two from Russia, of which the latter is a minisheet showing Picasso with one of his Peace Doves, designed for posters for the World Congress of Peace Partisans. This image, made in 1949, was already so pervasive that it was used for a design issued by the People’s Republic of China in 1950! (I think this must be the earliest Picasso stamp in existence.) And yet the very next year saw the issuance of another (different) Picasso dove, Flying Dove, on stamps of both Czechoslovakia and the PRC (the triangular stamp). A much later stamp from Malagasy (1981) shows the artist’s 1962 Dove of Peace. Probably the most famous of Picasso’s anti-war works, of course, is the haunting Guernica (1937), seen on stamps of Spain, Czechoslovakia, and Cameroun. We begin the second collage with examples drawn from the famous Blue Period (1901-04): Harlequin and his Companion (Les deux saltimbanques), The Glass of Beer, or Portrait of [the poet] Jaime Sabartes (Le bock or Portrait de Jaime Sabartes), and Motherhood (known variously as Desemparats, Maternité, Mère et enfant au fichu), all on stamps of Laos and the Maldives, and finally, the very blue Leaning Harlequin (1901). For the rest I threw up my hands and went random. The middle row offers Acrobat on a Ball (Acrobate à la Boule, 1905), Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907, a work that marked Picasso’s shift into his African-inspired and proto-Cubist period—see figures at right), Jug, Candle, and Enamel Pan (1945), Three Musicians (1921), and Woman Leaning 1 (1939); and the bottom row Pan’s Flute (1923), The Yellow Sweater (1939), The Piano (1957), Les Baladins (Mother and Child Acrobats, 1904-05), and Jacqueline in a Black Scarf (1960).

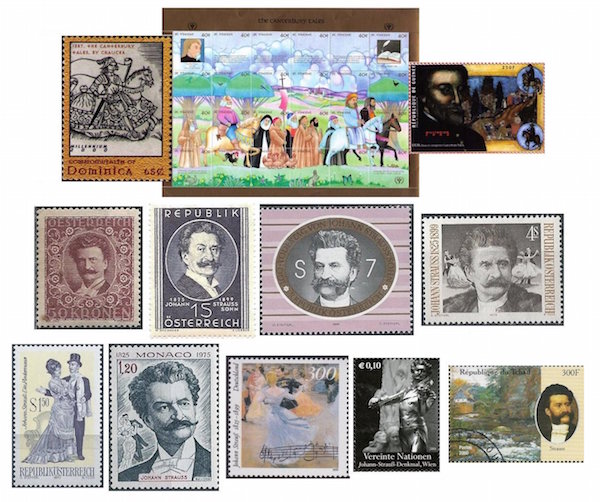

The birthday baked-meats do coldly furnish forth the funeral tables. The tombstone of Geoffrey Chaucer (b. c1343) states that he died on 25 October, 1400, but the stone was put up a century after his death, and the date cannot be authenticated. Postage stamps from Dominica and Guinea bracket a nice Canterbury Tales souvenir sheet from St. Vincent. As for musical settings of Chaucer’s poetry, we find them by Vaughan Williams (the short song cycle “Merciless Beauty” for high voice, 2 violins, and cello of 1921), George Dyson (a 90-minute choral work with soloists, “The Canterbury Pilgrims”, from 1931), and Peter Racine Fricker (a ballet, Canterbury Prologue, from 1951), among others.

I’ve mentioned before (ad nauseam?) that the earliest postage stamps ever issued to commemorate composers came out in 1922 in a Austrian set of seven. The Waltz King, Johann Strauss Jr (October 25, 1825 – June 3, 1899), was one of them (at far left). Of the bouquet (that’s a pun) of nine Strauss stamps displayed, five, not surprisingly, are Austrian. The other four are from Monaco, Germany, the United Nations, and Chad.

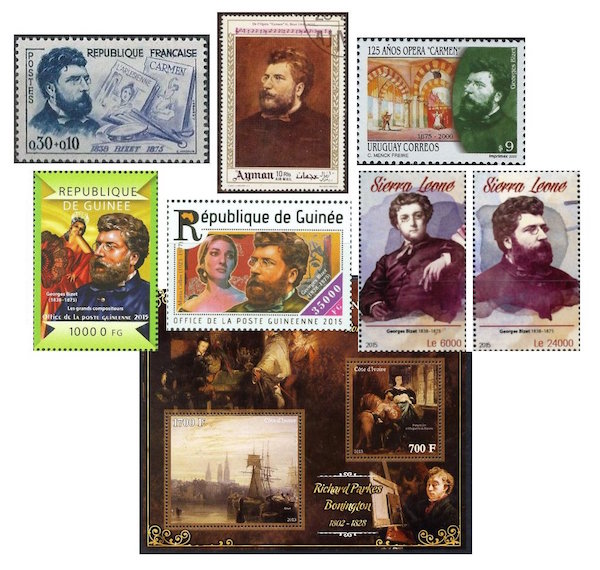

Georges Bizet (1838 – 3 June 1875) has almost as many, but their provenance is a bit more diversified. The earliest is the French one from 1960, and the others come from Ajman, Uruguay, and two each from Guinea and Sierra Leone. Monaco issued a beautiful set of Carmen stamps, but I already posted those back in March on the anniversary of the first performance of that opera.

Bizet’s early death at 36 was a great loss to music, but the English landscape painter Richard Bonington (25 October 1802 – 23 September 1828) died even younger, at 25. Born near Nottingham, he was taught painting in watercolors from his father, who had at one time been a drawing master. Young Richard had some of his pictures shown at the Liverpool Academy when he was all of 11. When he was 15, the family moved to Calais, his father having set up a lace factory there. In 1818, they opened a lace shop in Paris, where 16-year-old Bonington found a friend in Eugène Delacroix, himself only 19 at the time. After further study, Bonington exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1822 (he won a gold medal two years later) and began working in oils and investigating the process of lithography. For a time he and Delacroix shared a studio in Paris. Hitherto Bonington had concentrated on landscapes, and Delacroix suggested historical subjects. The sheet from Côte d’Ivoire shows one example of each: Rouen (1825) and François I and Marguerite de Navarre (1827). The art world was robbed of Bonington by the scourge of tuberculosis. Certainly he is not forgotten: he has a statue outside the Nottingham School of Art, and in his home town of Arnold both a theater and a primary school are named for him.

Russian author Dmitry Mamin-Sibiryak (October 25, 1852 – November 2, 1912) was born in the Urals and wrote his most famous fiction about life in the region. After going to seminary, Mamin-Sibiryak seemed to follow the same old story of artists in the 19th-century—the study of medicine, then of law, then tuberculosis, but luckily his health stabilized, and he was able to live what was then a reasonably long life. His first pieces, travel sketches called From the Urals to Moscow (1881-82), were published in a Moscow newspaper. More such matter came from his pen before he turned to fiction the next year with his popular novel The Privalov Fortune (1883). A second novel, Mountain Nest (1884), secured his reputation. He also wrote several books for children, including Tales for Alyonushka (1894–1896) and Summer Lightning (1897).

German artist and critic Walter Leistikow (1865 – 24 July 1908) managed to get himself removed from the Prussian Academy of Art in Berlin for “lack of talent”, but, undeterred, he took private lessons and a few years later, in 1886, held his first exhibition at the Berlin Salon. In 1892 he joined a group of anti-establishment artists calling themselves The Eleven (Die-XI, or Vereinigung der XI). Soon he tried his hand at fiction writing with a novella (1893) and a novel (1896), but his main area was in the visual arts, not only with painting but also graphic design and design of furniture, carpets, etc. He had a great fondness for painting the outdoors, as exemplified by From the Grunewald (c1907). The stamp shows another Berlin landscape, Am Schlachtensee. In the last year of his life, suffering terribly from syphilis, he committed suicide with a firearm.

Belgian bass-baritone Hector Dufranne (25 October 1870 – 4 May 1951) was the first Golaud (as seen on the stamp) in Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande in 1902, the first Don Iñigo Gomez in Ravel’s L’Heure espagnole (1911), and the first Don Quixote in the stage première of Master Peter’s Puppet Show by Manuel de Falla (1923). He appears in the first complete recording of L’Heure espagnole (1931) and can also be heard in a number of recordings made between 1904 and 1928.

Turkish folk musician and poet Âşik Veysel Şatiroğlu (25 October 1894 – 21 March 1973), more commonly referred to without the final name, was a virtuoso on the bağlama, a stringed instrument illustrated on a stamp I’ve placed adjacent to his. Misfortune seems to have dogged Veysel all his life. At seven he contracted smallpox and lost the sight in his left eye, some time thereafter suffering an accident that left him totally blind. Shortly after his marriage his first child died after just ten days, his wife left him for another man, his parents died within a couple of years of each other (while Veysel was still in his twenties), and his daughter also died young. It’s hardly surprising that his music tends to the melancholy with a focus on mortality. Greatly admired as a minstrel, songwriter, and folk poet, he was a founder of the Association for Preservation of Folk Poets in 1931, which organized the Fest of Folk Poets that year, and he taught the bağlama for decades.

From neighboring Greece, but of a later generation, comes Panagiotis “Takis” Vassilakis (October 25, 1925 in Athens), an artist whose work has been very popular in France. His early life having been disrupted by the occupation during World War II and the immediately succeeding Greek Civil War, he was almost entirely self-taught as an artist. He expanded to the plastic arts in 1946. In 1953-54 he was in London, after 1955 in Paris. He is in a sense both an inventive follower of the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk of the 19th century and a pioneer, combining art forms (and science) as early as 1957, when he anticipated what we now call “Street Art”. Around that time he began working with magnetic fields, creating sculptures he described as “télémagnétiques“. By 1963 he had taken a new approach by collaborating with American composer Earle Brown in a piece entitled the “Sound of Void”. In the late 60s he was at MIT, where he developed a new idea, Sculpture hydromagnétique, wherein liquid is suspended by electromagnetic forces. Continuing to explore the combinations of light and sound, he worked with a ballet company and began writing his own music. He wrote the score for Costas Gavras’ film Section spéciale in 1974. The French stamp from 1993 seems to eschew multimedia and keep things simple with one of Takis’s two-dimensional abstracts.

Russian soprano Galina Vishnevskaya (25 October 1926 – 11 December 2012) became a member of the Bolshoi Theater in 1953. Two years later she married her third husband, Mstislav Rostropovich, with whom she made many recordings (he on such occasions temporarily putting aside his cello for the piano or the conducting baton). Vishnevskaya made her Met debut in 1961 (Aida) and her La Scala debut in 1964 (as Liù in Turandot). The couple left the USSR in 1974. Their daughter Elena is a pianist, composer, and philanthropist. Russia issued this Vishnevskaya stamp just three years ago. The medal shown is the Russian (not Soviet) order “For Merit to the Fatherland”, awarded to the soprano in the last week of her life by the otherwise not so nice Mr. Putin.

French actress Annie Girardot (25 October 1931 – 28 February 2011) was thrice chosen for the César Award, the first time for best actress in 1977 for Docteur Françoise Gailland, then for best supporting actress in 1996 for Claude Lelouch’s film of Les Misérables (1995) and in 2002 for The Piano Teacher. Girardot was a resident actor at the Comédie Française from 1954 and entered the film world the next year. In 1960 she appeared in Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers (1960). (Visconti’s birthday is eight days away.) By the 1970s, she was the highest paid actress in France, with her portrayals of strong, hardy, independent women making her a symbol of the feminist movement. Her career went into decline in the 80s, but the Les Misérables performance signaled her comeback. She was afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease in the last years of her life.

The multiple professional hats of Micheál Mac Liammóir (25 October 1899 – 6 March 1978) cover acting, writing, and painting, among other things. His birth name was Alfred Willmore, and under that name he was one of the foremost child actors on the English stage of his day. He performed in Peter Pan (along with age-mate Noël Coward) for several seasons. As a young man he studied painting, an art he pursued all his life. On tour in Ireland, Willmore fell in love with the country and with fellow actor Hilton Edwards, with whom Willmore would spent much of his life. He also changed his name to Micheál Mac Liammóir and learned the language, writing much of his work, including three volumes of autobiography, in Irish (later translating them into English himself). Mac Liammóir and Edwards co-founded Dublin’s Gate Theatre in 1928. Many years later his performances included, most notably, the role of Iago in Orson Welles’s film version of Othello (1952; Hilton Edwards also had a role in the film), a one-man show, which Mac Liammóir wrote, called The Importance of Being Oscar (1960), and the narration for Tony Richardson’s 1963 film Tom Jones.

This day (October 25) is called the feast of Crispian, and so we conclude, we few, we happy few, with a stamp for King Henry V.

No stamps for seminal French film director Abel Gance (25 October 1889 – 10 November 1981), nor for three superior writers in English: John Berryman (October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972), Anne Tyler (born October 25, 1941), and Zadie Smith (born 1975).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.