The Arts on Stamps of the World — September 16

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

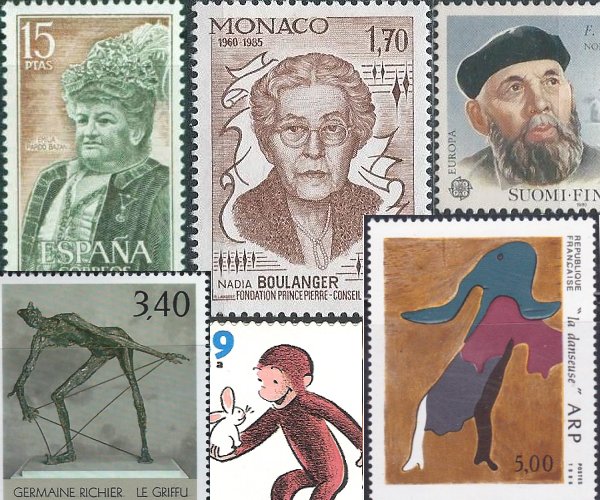

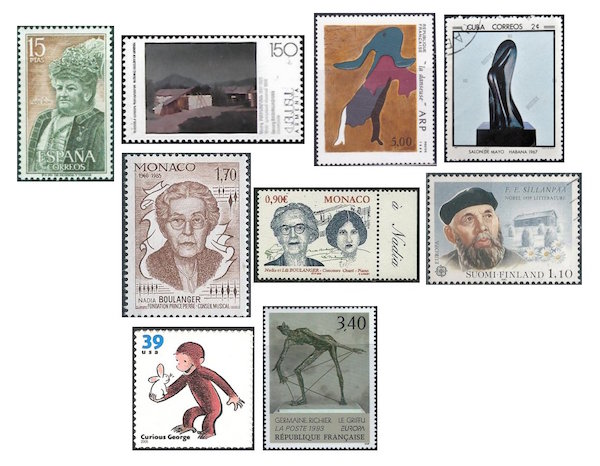

Spanish novelist Emilia Pardo Bazán (16 September 1851 – 12 May 1921) was fortunate enough to have a father who believed in the rights of women, but even so her formal education had to end prematurely, as she was not allowed to attend college. At 16 the young noblewoman married, developed an interest in political matters, and turned to writing. Already fluent in several languages, she won an essay competition in 1876 and began producing articles for a religious magazine. Her first novels, though, strove to emulate French realism and made a mark on the literary scene. She went on to write what is considered the first Spanish naturalist novel, La Tribuna, in 1883. A pioneering feminist, she achieved a number of academic firsts in the earliest years of the new century. She inherited the title of Countess in 1908 and in 1910 was appointed to the Council of Public Instruction by royal decree.

Armenian painter Gevorg Bashinjaghian (16 September [O.S. 28 September] 1857 – 4 October 1925) was born in a province of eastern Georgia. After preliminary art studies he attended the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg beginning in 1879. His focus was on landscapes, examples of which are Birch Grove (1883), Ararat (1912), and Countryside View (1888), as seen on the stamp.

An artist much better known in the West is Jean Arp, or Hans Arp—he used the names interchangeably depending on his surroundings, and this was in part due to his birthplace of Alsace-Lorraine. Arp (16 September 1886 – 7 June 1966) studied at his native Strasbourg, in Paris, where he published some poems, and in Weimar. Arp was a founding member of both the Moderne Bund in Lucerne and the Dada movement in Zürich, exhibited with Der Blaue Reiter and with the surrealists, though later he split with the latter group and joined the Abstraction-Création. He was married to the artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp. His work is represented on stamps with The Dancer (1925) and Torso of a Muse (1960-61).

The list of those who studied with Nadia Boulanger (16 September 1887 – 22 October 1979) is of such length that one is tempted to see her as the sacred fount of all musical education in the 20th century. Sometimes it seems as if there are fewer prominent musicians who didn’t study with her than there are those who did. She came from a musical family, including short-lived younger sister Lili, but curiously in early childhood had an aversion for music, until she experienced a volte face at the age of five. She herself studied at the Paris Conservatory (from the age of nine) with Gabriel Fauré and others. She won a number of firsts but decided against a career as a composer. Boulanger was active as a conductor, the first woman ever to lead some world-class orchestras, including the BSO (1938) (also the New York Philharmonic and the Philadelphia Orchestra, both in 1939). She led the premières of such works as Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Oaks Concerto and Copland’s Symphony for organ and orchestra, which was written for her. Most of her legion of students came to her flat in Paris, but Boulanger also taught at the Juilliard School, the Longy School (during World War II), and the RCM. The Principality of Monaco has issued two Boulanger stamps. We’ve already seen (last month) the one showing both sisters; it is here reprised. The other one honors Nadia alone.

The first Finnish writer to win the Nobel Prize in literature was Frans Eemil Sillanpää (16 September 1888 – 3 June 1964), who was awarded the distinction in 1939. He wrote about peasant life in his country, which he knew well from his own background. He was fortunate enough to be able to attend school and went on to study medicine in Helsinki, where he became acquainted with painter Eero Järnefelt, composer Jean Sibelius, and author Juhani Aho, whose birthday was earlier this week. Sillanpää began publishing his work as early as 1916, but it was his 1931 novel Nuorena nukkunut (published in English as The Maid Silja) that earned him his international reputation.

The co-creator of Curious George was also born on September 16th. Hans Augusto Rey (born Reyersbach, 1898, died August 26, 1977), known as H. A. Rey, was born in Hamburg, Germany, as was his wife and collaborator Margret. They met in that city and oddly enough encountered each other again in Brazil some years later. They married and moved to Paris, where they put out a children’s book called Cecily G. and the Nine Monkeys, in which one of the characters was Curious George. As they were both Jewish, in June 1940 they made a dramatic exit from Paris, carrying manuscripts with them on their bicycles. They crossed into Spain, proceeded to Lisbon and thence back to Brazil. The first Curious George book was published in New York in 1941. The couple wrote a total of seven books in the series, with Hans working mainly on the illustrations and Margret the stories, although they shared some elements of the work. One of Rey’s interests was astronomy, and he created a number of alternate configurations for the constellations. The culmination of this endeavor was the book The Stars: A New Way to See Them (1952), and Rey’s versions have caught on with a number of astronomy guides. In their later years the Reys lived near Harvard Square.

French sculptor Germaine Richier (16 September 1902 – 21 July 1959) worked with Antoine Bourdelle (birthday next month) from 1926 until his death three years later. Although she took a more-or-less classical approach to sculpture, her subject matter was often unworldly or fantastic, involving for example human-animal hybrids. But her later style was more abstract. In her attempt to capture anguish in form, Richier caused a bit of a ruckus with her statue of Christ, designed in 1950 for the church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce du Plateau d’Assy. In this work she depicted the Christ figure faceless and melding with the wood of the cross. The bishop of Annecy was not favorably disposed and ordered the sculpture removed. It was restored to its place in 1969. The stamp issued in 1993 shows Richier’s piece Le Griffu (1952). (This word is not in my Cassell’s.)

For all six of our remaining birthday people, four of whom have died within the last few years, we turn to popular culture. English director Guy Hamilton (16 September 1922 – 20 April 2016) was known mainly for his having helmed four of the James Bond movies. Following some interesting wartime experiences, Hamilton worked as an assistant director with Carol Reed and on The African Queen (1951). He was offered the first James Bond film, Dr. No (1962), and turned it down, but he reconsidered for Goldfinger (1964) and later directed Diamonds Are Forever (1971), Live and Let Die (1973), and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). He died at his home in Majorca, aged 93. As there no stamp for him personally, I show another of the plethoric 007 issues.

Of Lauren Bacall (born Betty Joan Perske; September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014), B.B. King (born Riley B. King; September 16, 1925 – May 14, 2015), and Peter Falk (born Peter Falk; September 16, 1927 – June 23, 2011), little need be said here. All the stamps, like the James Bond one I used for Guy Hamilton, are of African origin.

And so is the minisheet for West Side Story, which we use to wish George Chakiris (born September 16, 1934) a happy birthday. In addition to his appearance as Bernardo in the classic musical, Chakiris played Chopin in the fine BBC television miniseries Notorious Woman—about George Sand—filmed in 1974.

I think David Seth Kotkin (born September 16, 1956), better known by the stage name David Copperfield, is the first magician—other than Harry Houdini—we’ve had occasion to address in this column. Copperfield has garnered 21 Emmys, secured 11 Guinness World Records, and sold 33 million tickets and grossed over $4 billion, more than any other solo entertainer in history. Both the stamps come from the Caribbean, Dominica and Nevis.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.