The Arts on Stamps of the World — September 1

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

We usher in the month of September with the Bohemian Baroque architect Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer (1 September 1689, Prague – 18 December 1751). He came of a family of architects and brought to completion some of the projects his father Christoph Dientzenhofer left unfinished at the time of his death, just as Kilian’s son-in-law Anselmo Martino Lurago would in turn do for him. Dientzenhofer worked under Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach and Johann Lucas von Hildebrandt, two of the foremost Austrian architects of his day, and left his mark on the city of Prague and environs (as well as in Moravia and Silesia). Examples on stamps include, from left to right, the St. Nicholas Church on Prague’s Old Town Square (1732-35; stamp of 1931) and his redesign of St. Loreto in Hradčany (1723; stamp 1996). In addition another issue prettily shows two windows from Dientzenhofer’s Michna Palace (1712-20), his first building in Prague. This summer palace, sometimes called Villa Amerika after a restaurant that once occupied it, now (since 1932) houses the Antonín Dvořák Museum. (Dvořák’s birthday is a week from today.)

If the name Engelbert Humperdinck (1854 – 27 September 1921) within the context of opera surprises you, you may not know that the original possessor of that name was a German composer best known for his Hänsel und Gretel (1893) and his association with Wagner. Since 1965, when the British crooner Arnold Dorsey adopted the name, Humperdinck has probably been spinning in his grave, thinking, “Please release me, let me go.” Though Hansel and Gretel (premiered under Richard Strauss’s baton) is the only work by EH still in the repertoire, there is another lovely fairy tale opera called Die Königskinder (The King’s Children) of 1897, which received a fine recording eighty years later. In that opera, Humperdinck was the first composer to employ the technique of Sprechgesang (literally “speak-singing”), well before Schoenberg and “Pierrot Lunaire”. Not only is a pop singer named for him, so also is the main belt asteroid 9913 Humperdinck, discovered in 1977, the same year, coincidentally, of the appearance of the aforementioned recording of Königskinder. On 26 September 1921, Humperdinck went to see a performance of Weber’s Der Freischütz that was directed by his son Wolfram, the young man’s first effort as a stage director. The composer had a heart attack during the performance and died the next day.

For me, one of the rewards of this project is the discovery of names of fascinating creative talents for the first time, and one such (for me) is Russian Symbolist poet Innokentiy Annensky (September 1, 1855 – December 13, 1909). He is most important for having paved the way for Symbolism in Russia, at first by providing sensitive translations of the French exemplars of the movement such as Baudelaire and Verlaine, then by writing his own poems in their style, but in his own individual voice. The resulting influence he had on the subsequent generation, poets like Akhmatova (one of his students) and Mandelstam, was of great importance. He himself began writing poetry in the 1870s but was determined not to publish any of it until he had achieved maturity. Annensky studied philology with a concentration on comparative linguistics at St. Petersburg University. He became a teacher of classical languages and literature at Tsarskoe Selo and directed the school there from 1886. He translated all of Euripides starting in 1890 and then began a series of modern plays inspired by ancient Greek models. Annensky also wrote criticism on Russian authors in language that was itself highly expressive. His first poetry collection appeared only in 1904, when he was nearly fifty, and even then he used a pseudonym. (This was “Nik. T.-o”, suggesting Nikolai as the first name, but nikto in Russian means “nobody”.) His second book, Cypress Box, was considered more valuable, but Annensky did not live to see its publication, which occurred just days after his death from a heart attack at the Tsarskoe Selo railway station in Saint Petersburg. He has no stamp, but appears on a Russian postal card of 2005.

Tarzan creator Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) just got his first American stamp three years ago, although we’ve seen Tarzan stamps from other nations in our tributes to Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan. Burroughs was born in Chicago to a family that had been in North America since his ancestor Edmund Rice settled in Massachusetts in 1638. Burroughs went to Phillips Academy, drifted, worked on a ranch in Idaho, and began writing fiction in 1911. He had read stories in pulp magazines and knew he could do better. The readers were certainly happy, and Burroughs met with success early on, such that he could devote himself to writing full-time. Tarzan was an early creation, first appearing in the novel Tarzan of the Apes, serialized beginning in October 1912. Within a few years he was able to purchase a ranch in California that he called “Tarzana”. The name was adopted for the community that rose up around the ranch when the town was incorporated in 1927. Burroughs, as you may know, never saw Africa, but he did get as far as Hawaii, where he happened to find himself when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. He became a war correspondent despite being over 60 years of age. Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote almost 80 novels, among them the Mars (or Barsoom) and Pellucidar series. (He had never been to those places, either.)

Swiss composer and conductor Othmar Schoeck (1886 – 8 March 1957) concentrated on art songs and song cycles, but he also wrote five operas, chamber music, and several works for orchestra. I particularly recall a very appealing Horn Concerto (1951).

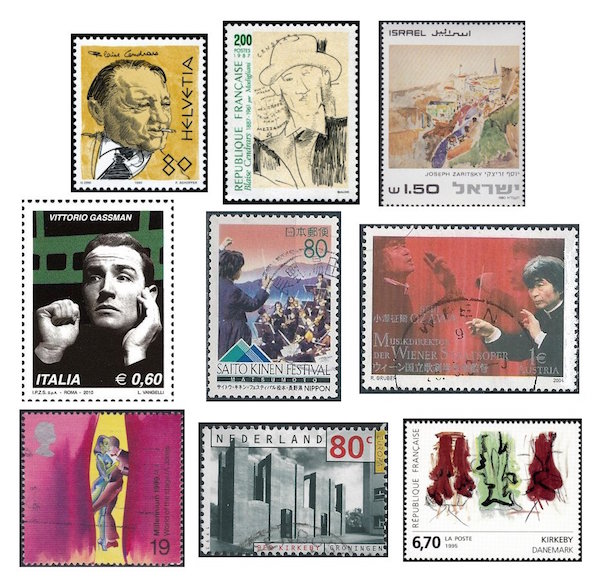

Another Swiss born on September 1 was the writer who used the nom de plume Blaise Cendrars (1887 – 21 January 1961). He was born Frédéric-Louis Sauser and would come to have an influence on European modernist literature comparable to that of Annensky on Russian Symbolism. An underachiever at school, Sauser was apprenticed to a Swiss watchmaker in St. Petersburg, Russia, where he began to write poems. Back in Switzerland, he was a medical student at the University of Berne, then traveled to Paris and New York. There he wrote what is considered one of the first modernist texts, his long poem, Les Pâques à New York (Easter in New York, 1912), using the pseudonym Blaise Cendrars for the first time. Back in Paris he met many prominent artists and had a mutually productive friendship with Guillaume Apollinaire. After the war, in which Cendrars lost his right arm while fighting in Champagne in 1915 (he became a French citizen the next year), he formed friendships with Chagall and Léger and, under their influence, wrote innovative abstract short verse published with the title Dix-neuf poèmes élastiques (Nineteen Elastic Poems) in 1919. He gathered more distinguished artistic friends, Henry Miller, Amedeo Modigliani (who painted his portrait, which can be seen on the French stamp), and John Dos Passos, who introduced Cendrars’ work to an American audience with his translations of the long poems “The Transsiberian” and “Panama”. Cendrars survived the Occupation despite being on the Gestapo’s watch list and after the war became fascinated with film, as well as trying his hand at short stories and novels, including an admired four-volume autobiographical series.

The important Israeli artist Joseph (Yossef) Zaritsky (September 1, 1891 – November 30, 1985) came from the Ukrainian part of the Russian Empire. Zaritsky attended the Academy of Arts in Kiev and served in World War I from 1915 to 1917. With the pogrom of 1919 he and his family fled to Bessarabia and four years later immigrated to Jerusalem. He spent some time in Paris in the late twenties and brought the French influence back when he returned. Many years later there was a contretemps when David Ben-Gurion made a slighting remark about one of Zaritsky’s paintings, and it was shifted from its more central location in the exhibition, as a result of which there was a very public brouhaha, and Zaritsky destroyed the painting. A decade later, though, he was awarded Israel’s prestigious Sandberg Prize. The stamp shows one of the artist’s views of Jerusalem.

The well-known Italian actor Vittorio Gassman was born on this date in 1922 in Genoa. His father was German, and the name was originally spelled with two Ns. He attended the Accademia Nazionale d’Arte Drammatica in Rome and made his stage debut in Milan in 1942. His first film, from 1946, was Preludio d’amore, after which his movie career took off. He continued working on the stage, too, with Luchino Visconti’s company, in plays by Shakespeare (As You Like It), Ibsen (Peer Gynt), and Tennessee Williams (he played Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire; I love the Italian rendering of this title: Un tram che si chiama desiderio). In 1952 he co-founded the Italian Arts Theater, which put on the first unabridged Hamlet in Italy, and the Bottega Teatrale di Firenze. Gassman had a success with a television series called Il Mattatore (Spotlight Chaser), a title that stuck with him as a nickname. He was married, among others, to Shelley Winters. Late in his career he provided the voice for the character of Mufasa in the Italian version of The Lion King. Vittorio Gassman died on 29 June 2000. He was remembered on an Italian stamp ten years later.

Former BSO conductor Seiji Ozawa turns 82 today. The stamp at bottom left was issued in 1996 for the Saito Kinen Festival, co-founded by Ozawa four years earlier. Although not named on the stamp, and with his back turned to us, the conductor is clearly Seiji. (Another conductor, Patrick Botti of the Waltham Symphony Orchestra, tells me that Ozawa could easily be recognized from the picture, if not by the hair, then by the conducting stance.) Another Japanese stamp depicting Ozawa appears on one of a large set of millennial stamp sheets issued in 2000 (not shown). He is featured, too, on an Austrian stamp honoring his association with the Vienna State Opera, of which he was principal conductor from 2002 to 2010.

British pop artist Allen Jones (born 1 September 1937) is exactly two years younger than Ozawa. Jones works in painting, sculpture, and lithography and has taught in Germany, the US, and Canada. His best known work, and one that is representative of his preoccupation with eroticism, fetishism, and BDSM, is Hatstand, Table and Chair, which drew opprobrium for its apparent objectification of women, though Jones declares he was attempting to draw attention to that very issue. A much less controversial piece is the design he provided for one of Britain’s extensive series of millennium stamps, this one representing the “world of the stage”.

Another artist active in both painting and sculpture, as well as in poetry and filmmaking, is Per Kirkeby, born in Copenhagen a year to the day after Jones. He studied arctic geology, a discipline that makes itself felt in much of Kirekby’s work, particularly his quasi-architectural pieces like the one in Groningen shown on the Dutch stamp of 1993. Less reflective of that influence, perhaps, is the French stamp from 1995, showing one of Kirkeby’s abstract paintings.

Worthy of mention, I think, if not of a stamp, is the English writer Eleanor Hibbert (1 September 1906 – 18 January 1993), who wrote 200 books—romances and historical fiction under the pen names of Jean Plaidy, Victoria Holt, and Philippa Carr.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.

I saw Gassman in “Viva Vittorio”– and, yes, it was an ill advised venture and disappointing. But still, I got something out of it. It was one of those learning experiences….