Visual Arts Commentary: The Berkshire Museum Violates Ethics to Sell 40 Works for $50 Million

Why is The Berkshire Museum a sinking ship?

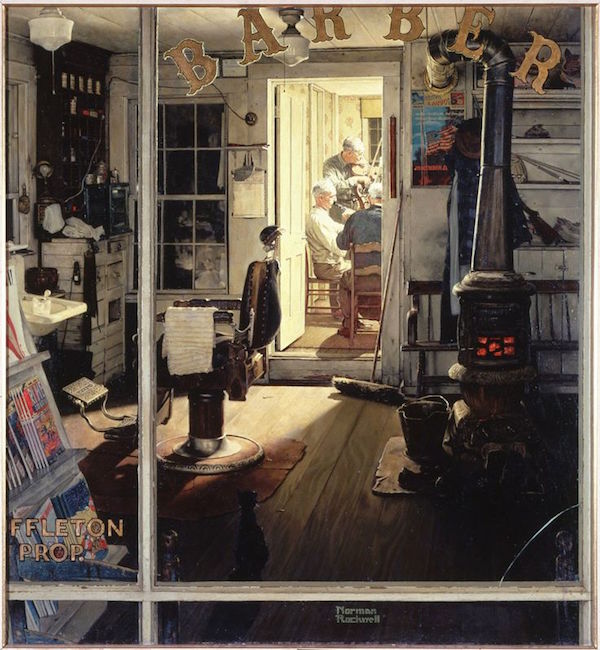

Norman Rockwell’s painting “Shuffleton’s Barbershop” is on the auction block.

By Charles Giuliano

114 years ago Zenas Crane founded the Berkshire Museum in the tradition of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum — a self-consciously eclectic mix of fine arts, science, and natural history.

There were hefty annual checks from the wealthy Crane family (of paper-making fame). For years there was free admission. Eventually that stopped, as well as the yearly Crane donations.

Initially it was The Berkshire Museum, but today it would be more accurate to call it A Berkshire Museum. Per capita there are twice as many cultural institutions and non-profits than the national average in the Berkshires. And that means there is a fierce competition among arts organizations for support. And the sources are limited. Another factor hampering the Berkshire Museum: mediocre management, marketing, and programming.

For the past ten years the museum has run an annual $1 million deficit. The board talked about shutting down the institution after eight years of debt. Under director Van Shields there have been cutbacks for the past six years. The museum cannot afford a curator, which has brought about lackluster programming and expensive rented shows. Some other reasons for the museum’s troubles: studies show a declining Berkshire population. Cutbacks in the schools make the area unattractive to young families.

Still, at the same time, other Berkshire cultural institutions — Tanglewood, Jacob’s Pillow Dance, four equity theater companies, Norman Rockwell Museum, MASS MoCA, and the Clark Art Institute — are thriving to the point that they have dramatically expanded. There has been a steady increase of arts tourism and a hotel building boom. Two more museums are planned for North Adams.

In this rising tide, why is Berkshire Museum a sinking ship? Less than ten years ago, under former director Stuart Chase, there was a $9 million renovation. He worked closely with artists. That stopped with the hiring of Shields, who has shown little or no interest in fine arts and regional artists. Thus the drastic decision of Shields and the museum’s board to sell 40 choice works from the collection and “reboot” as an interactive science and natural history museum that caters to children and school groups.

Given a presale estimate of $50 million from auction house Sotheby’s, the board plans to raise another $10 million. The aim is to retire the debt, spend $20 million for renovation, and pocket $40 million for the institution’s endowment. The Berkshire Eagle reported, at first, that these strategies to save the museum — for “the next 114 years” — were met with enthusiasm, including a glowing editorial in the newspaper.

Information about the museum’s approach was revealed slowly. Two beloved Norman Rockwell paintings are set to go on the auction block. Years before there was a museum in his name, Rockwell gave Shuffleton’s Barbershop and Shaftsbury Blacksmith Shop in 1959 and 1966, respectively, to his Berkshire neighbors.

Ethical issues have surfaced, pouring some rain on the museum’s lucrative parade. I wrote a letter to the Berkshire Eagle quoting from the guidelines of Association of American Museum Directors. They state that museums may deaccession only for the sake of refining and enhancing their collections. Money from the sales of art may not be applied for any other purpose — without evoking sanctions.

The letter was posted online and the museum lobbied, successfully, to have it deleted. Shields told the Eagle editors that he was not a member of AAMD; neither was he the director of an art museum. Several days later the Eagle ran a revised version of my letter. The local conflict became national news when Laurie Norton Moffett, director of the Rockwell Museum, passionately urged the museum to “pause” and reconsider the sale.

There have been — above the fold — op-ed pieces and letters in the Eagle on a daily basis ever since. There has been coverage of the art sale in the NYTimes, Boston Globe, Wall Street Journal, and on NPR.

A thumbs-up game changer came in the form of Joe Thompson, director of MASS MoCA, who waded in with support for the sale. His key phrase was “Let’s get real.”

An Eagle editorial, however, decried the museum for stonewalling and refusing to answer key questions about what it was up to. The museum has had a PR firm on salary for eight months and has upgraded its presence, supplying air-brushed replies to a barrage of negative stories and commentaries.

Under pressure, the museum released a list of 38 works, in addition to its Rockwells, that are to be sold. These include paintings by landscape artists Albert Bierstadt, Ralph Albert Blakelock, Frederick Edwin Church, George Inness, and Thomas Moran. George Henry Durrie painted scenes converted into lithographs by Currier and Ives.

In addition are 18th and 19th century works by Benjamin West, Charles Willson Peale and Rembrandt Peale, John LaFarge, impressionist Thomas Wilmer Dewing, and sculpture by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. There are two Calders, Dutch Masters and French salon artists as well as examples of impressionism, fauve, modernism, Chinese, and Japanese art.

If Shields no longer is running an art museum, what will become of its collection? Under Chase there were exhibitions and acquisitions of works by established and emerging Berkshire artists. These included shows featuring photographer Gregory Crewdson, who has used Pittsfield for elaborate set pieces. Painter Stephen Hannock exhibited major works and studies, simultaneously in Pittsfield and Newcastle, England in a series commissioned for his hometown by the artist’s musician mate, Sting. Works by Hannock and Crewdson sell for six figures. The museum owns one by each.

Under the intense media scrutiny, arguments running pro and con, Shields and The Berkshire Museum have waffled on their message.

Other than announcing the strategy of ridding the museum of 40 saleable works (cherry-picked from the collection), there has been no straight talk regarding the future of what remains. It has been admitted (via dribs and drabs) that the institution owns 40,000 objects, including 2,395 art works. The breakdown of the latter: 440 paintings, 91 sculptures, 248 Asian works, and 277 works on paper.

Frederic Edwin Church’s “Valley of the Santa Ysbel.” Up for sale.

An astute director and keen curator should have deaccessioned and upgraded the collection long ago. In the oligarch-fueled art market, Chase sent two of the museum’s Russian modernist painting to auction, raising $7 million. Much of that money went for climate control in the museum, which was a legitimate use for the sales money — to preserve and protect the collection.

Current Berkshire Museum renovation plans include ripping out the historic, art deco Crane room, as well as the auditorium, with its two early (and iconic) Calder mobiles. That redesign will create an enormous lobby with a soaring atrium and aquarium.

A letter recently published in the Berkshire Eagle, signed by Rockwell’s three sons (Peter Rockwell, Thomas Rockwell, and Jarvis Rockwell) as well as his grandsons (Barnaby Rockwell, Geoffrey Rockwell, and John Rockwell) critiqued the decision: “Norman Rockwell didn’t give Shuffleton’s Barbershop to finance the Museum’s renovation plans. He gave it hoping the people of the Berkshires would see it and enjoy it.”

“This is not easy. I love these works of art,” Shields spins in his reply. “We are very excited about what we are doing. But we totally understand why some people are not.”

Charles Giuliano is publisher/ editor of Berkshire Fine Arts. He will soon publish his fourth book since 2014, Gloucester Poems: Nugents of Rockport. This summer he will jury the annual show for Boston’s Galatea Gallery.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Stuart Chase, The Berkshire Museum