The Arts on the Stamps of the World — May 7

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

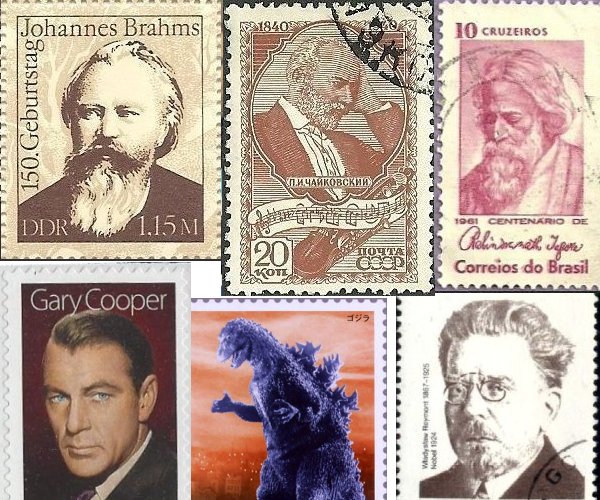

Two of the greatest masters of music, Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) and Pyotr Ilich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), happen to share this birthday. Also born on May 7 were the great Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore and several other people from the arts who have been remembered on stamps of the world. May 7 is also the anniversary of the first performance of Beethoven’s Ninth in 1824.

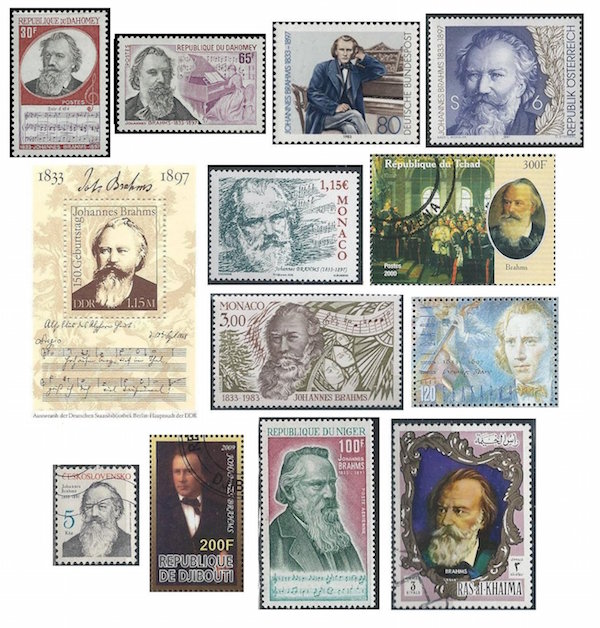

To the best of my knowledge the oldest Brahms stamps in the world were issued only as recently as 1972 (!) by the nation of Dahomey (!). I find it rather surprising that Germany and Austria have so far issued only one Brahms stamp apiece (plus one minisheet from East Germany), while there are two from Monaco (1983 and 2008). I add a further half dozen from elsewhere (a lovely item from Niger), but there are quite a few other Brahms stamps not in my collection.

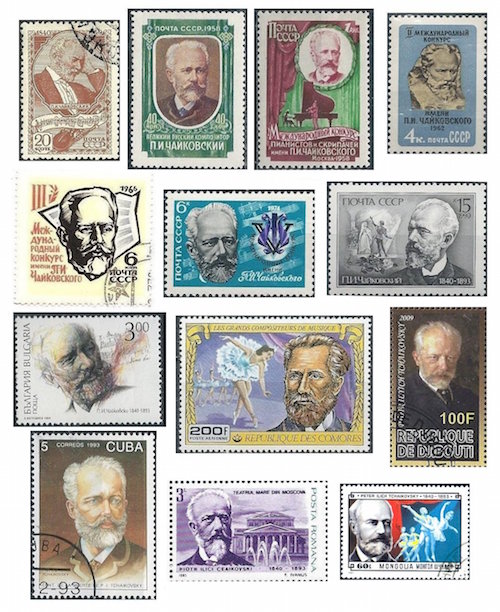

The same can be said of Tchaikovsky, who has been much more frequently celebrated on stamps than his great German contemporary. Part of the reason for this is that many stamps commemorate Tchaikovsky’s ballets, especially Swan Lake, so I limit my presentation today to portrait issues. By contrast with Brahms, the first Tchaikovsky stamps came out in Russia for his centenary in 1940. Our Tchaikovsky page begins with one of them and continues with more Soviet issues, winding up with examples from Bulgaria, the Comoros Islands, Djibouti, Cuba, Romania, and Mongolia.

I am shocked—shocked—that there appears to exist nowhere in the world a stamp honoring Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889), nor is there one for Elizabeth. O tempora, o mores!

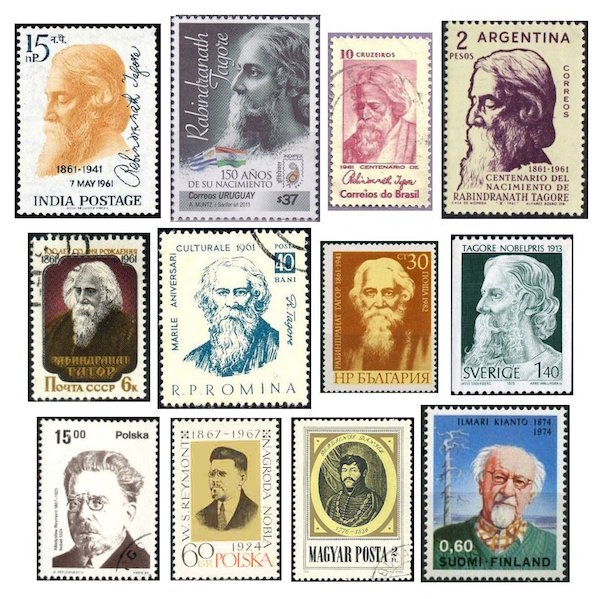

Our third stamp collage is devoted entirely to writers. The first non-European to be awarded the Nobel Prize for literature (1913), Rabindranath Tagore (7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) was a remarkable polymath who not only is regarded as one of the greatest voices in the literature of India but also composed well over 2,000 songs and, at the age of sixty, took up drawing and painting! In addition, many Western compositions owe their existence to his (translated) writings. Leoš Janáček attended a lecture given by Tagore in 1921 and wrote one of his most important choruses on the poem “The Wandering Madman”. 1924 saw the première of Zemlinsky’s Lyric Symphony on texts from “The Gardener”, which also provided material for a 1918 song cycle by Szymanowski. The worldwide breadth of his appeal can be seen in works by such ethnically and stylistically variegated composers as Ippolitov-Ivanov (Russia), Paul Creston and Gardner Read (US), Frank Bridge and the late Jonathan Harvey (Britain), Respighi, Alfano, and Casella (Italy), Milhaud, André Caplet, and Louis Durey (France), Manuel Ponce (Mexico), Hanns Eisler and Stefan Wolpe (Germany), Grażyna Bacewicz (Poland), and Hendrik Andriessen (Netherlands), to give only a partial list. This appeal is reflected also in stamps from all over the world: India, Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina, Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Sweden, and there may well be others.

It so happens that another Nobel laureate for literature was born on the same day as Rabindranath Tagore just six years after him. Polish novelist Władysław Reymont (vwa-DEE-swahf RAY-mont; 7 May 1867 – 5 December 1925) won the Prize eleven years after Tagore, in 1924. He had taken some time to find his niche. Trained as a tailor, he ran off with an itinerant theater troupe, then with a spiritualist, then with another group of actors. It seems he had no gift for acting nor for communing with the dead, but in 1892 he was able to sell some travel writing to a Warsaw journal, had some success with his stories, and turned at last to the novel. His third work in that form, The Promised Land (Ziemia obiecana, 1897) would become his best known and was twice made into films, the first a 1927 silent, the second a 1975 production directed by Andrzej Wajda. The work that won him the Nobel Prize, though (over rivals Thomas Mann, George Bernard Shaw and Thomas Hardy, yet) was his four-volume novel, The Peasants (Chłopi, 1904–1909). His last work, incidentally, The Revolt (1924), directly anticipates by some twenty years George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

One of the earliest Hungarian Romanticists, poet Dániel Berzsenyi (BAIR-zhen-yee; 1776 – 24 February 1836) sought to reconcile the farming life with the literary world. Despite recurring ill health he did well as a farmer but keenly felt the dearth of erudite conversation and grew disappointed and melancholy. He wrote little poetry after 1810 and concentrated instead on scientific and aesthetic studies.

Finnish writer Ilmari Kianto (born Calamnius, 7 May 1874 – 27 April 1970) was the son of an evangelical pastor and studied philosophy and literature in Helsinki and Moscow. Among his early writings (published under the name Calamnius) are a roman à clef of his experiences in the military, The Wrong Path (1897), several volumes of poetry, and translations of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Tolstoy. His anticlerical novel Holy Wrath (Pyhä viha, 1908) was succeeded by perhaps his finest work, The Red Line (Punainen viiva, 1909), which deals with poor farmers in northern Finland. This book inspired Aulis Salinnen’s 1978 opera of the same name. One of Kianto’s poems, “Driftwood”, was also set by Sibelius in 1902.

And a writer begins our last collage for today. The Belgian Alphonsus Josephus de Ridder (7 May 1882 – 31 May 1960) used the pen name Willem Elsschot. He began as a poet but made more of a splash with his fiction. He had studied economics and so was well equipped to start up his own advertising agency after World War I, and his experience with that gave him the idea for a novel called Lijmen (1924, translated into English as Soft Soap). His seriocomic novels such as Kaas (Cheese, 1933) and Het been (The Leg, 1938) found both critical praise and popular acclaim, and a number have been made into films.

Luxembourgian pianist and composer of light music Lou Koster (7 May 1889 – 17 November 1973) also played as a violinist and wrote music on a bigger scale than her songs and piano pieces, such as the operetta An der Schwemm (At the Baths, 1922) and her last and largest score Der Geiger von Echternach (The Violinist of Echternach, 1972), a ballad for soloists, chorus and orchestra. Koster also occasionally took to the podium as a conductor and founded a vocal ensemble, “Onst Lidd,” in the 1960s. There is a Naxos CD of her orchestral music.

Now it’s movie time. The star of Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), The Pride of the Yankees (1942), and High Noon (1952), Gary Cooper (1901 – May 13, 1961), was born exactly ten years earlier than the man who directed the original 1954 Godzilla (Gojira), Ishirō Honda (1911 – February 28, 1993), who made many other Japanese monster (kaiju) movies. But his oeuvre was not at all limited to such classics as Rodan (1956), Mothra (1961), Destroy All Monsters (1968), and his final feature, Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975). He made many other films, and both before and after his kaiju career worked as an assistant under Akira Kurosawa. Honda functioned as directorial advisor, production coordinator, and creative consultant for Kurosawa’s last five films. Guinea and Mozambique have issued some colorful sheets devoted to Honda, but I include only a purple Godzilla stamp from his native Japan.

Ma Sicong (or Ma Szu-ts’ung; May 7, 1912 – May 20, 1987) was born in Guangdong province and studied violin in Paris. He undertook a successful round of concerts on his return to China and began composing substantial chamber works (a piano trio, two violin sonatas) and popular songs. When the Sino-Japanese War erupted in 1937, he wrote patriotic songs and led the Anti-Japanese Choir. He and his family were forced to flee repeatedly from Japanese advances in 1944, yet he composed his Violin Concerto in the same year. An opponent of the Kuomintang, he escaped their prosecution by moving to Hong Kong, then on the founding of the PRC was named director of the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. He was further persecuted, this time by the Communists, during the Cultural Revolution and again escaped to Hong Kong in 1967, thence to the United States, where he wrote his only opera Rebia, in 1980. He died in Philadelphia. His best known work is the movement “Nostalgia” from his 1937 “Inner Mongolia Suite”.

Eva Perón (7 May 1919 – 26 July 1952) is here because before becoming the second wife of Argentine President Juan Perón she had worked as an actress on the stage, on radio, and in some B-movies. Oh, and because of Evita.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony had its première 193 years ago today. A Mexican airmail stamp of 1970 quotes the famous “Ode to Joy” theme.

Someday I predict there will be stamps for writers Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (7 May 1927 – 3 April 2013) and Peter Carey (born 7 May 1943).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.