The Arts on the Stamps of the World — March 12

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

For today’s Artists on Stamps of the World we salute perhaps the most famous male ballet dancer of them all, Vaslav Nijinsky, along with French landscape architect André Le Nôtre, Italian writer Gabriele D’Annunzio, and several others less familiar to most of us. Two writers, both American, who should be remembered on stamps, aren’t yet, but probably will be one day, are Jack Kerouac (March 12, 1922 – October 21, 1969) and the late Edward Albee (1928 – September 16, 2016).

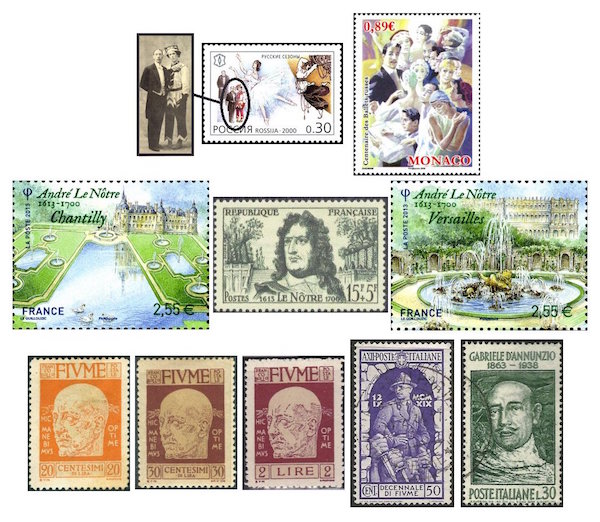

Nijinsky was born on March 12 (O.S. Feb. 28), but the year is uncertain, with 1888, 1889, and 1890 all being proposed. (At least one other source offers Dec. 17, 1889 as a further possibility.) He has no stamp specifically in his memory but appears on two dedicated to Russian ballet. The one from Russia, at left, shows a teeny-tiny Stravinsky and Nijinsky in a drawing based on a famous photo (included for your viewing convenience), and the one from Monaco presents a gathering of people associated with Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes. Nijinski is on the right (I think, wearing the yellow cap?) just above Stravinsky. Help identifying the other personages would be welcome. Poor Nijinsky was schizophrenic and danced for the last time in public in South America in 1917. Artur Rubinstein was another of the performers at that beneift concert in Montevideo and wept when he witnessed the dancer’s disorientation. Nijinsky was institutionalized repeatedly over the next thirty years. He died on 8 April 1950.

André Le Nôtre (12 March 1613 – 15 September 1700) followed in the footsteps of his father, overseer of the Tuileries Gardens under Louis XIII, so in that sense he was born with a green spoon in his mouth. He studied painting and architecture and entered the workshop of Louis’ court painter Simon Vouet. There he became friends with Charles Le Brun, with whom he would later collaborate, along with Louis Le Vau, at Vaux-le-Vicomte. Le Nôtre also studied for several years under François Mansart, father of the deviser of the Mansart roof. After work at the parks and gardens of Chantilly (see the stamp), Fontainebleau, Saint-Cloud, and Saint-Germain, Le Nôtre designed the park at Versailles (see the stamp) for Louis XIV. The stamp at center is from 1959 and is bracketed by a pair from 2013.

Say what you will of Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863 – 1 March 1938), he was undeniably a fascinating and forceful character with great gifts. The down side is that he was a protofascist, whose exploits in World War I (as a flyer he led a squadron of planes that buzzed Vienna with propaganda leaflets) made him something of a hero, but whose nationalist-miltaristic views were hardened by the conflict. (He also lost the sight of one eye in a flying accident during the war.) D’Annunzio demanded equality with the other victorious allied states for Italy and was so determined that the city of Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) be annexed that he occupied the city with an army and set up his own state, the Italian Regency of Carnaro. The three “Fiume” stamps seen here were issued during this period. A word about philatelic protocol: throughout the first century and more of philatelic history, a general rule has applied: living persons, with two exceptions, typically were not honored on stamps; the exceptions: reigning monarchs…and dictators. D’Annunzio’s approach was decidedly authoritarian. He employed the kinds of tactics from which Mussolini would learn: theatrical addresses to large crowds from balconies, public ritual, mandated conformity, the Roman salute, strongarm suppression of dissent, even use of the honorific “Duce“. In the event, Italy refused to annex the city, D’Annunzio declared war (!), and after an occupation of fifteen months (the war lasted just days), surrendered in December 1920. Apparently no prosecution followed. So now let us deal with D’Annunzio the writer. Born to privilege in Pescara (his wealthy father was the mayor), he published a volume of poetry when he was sixteen and produced a series of poetry and story collections in the 1880s. His first novel dates from 1889, his first plays from the 1890s, some of them written for his lover, the great actress Eleonora Duse. His writings (in their descriptions of violence, mental aberration, etc.) and his lifestyle bred controversy. He left for France in 1910 to avoid his debts and there worked with Debussy (Le martyre de Saint Sébastien) and Mascagni (Parisina). His play Francesca da Rimini was made into an opera by Riccardo Zandonai in 1914, and he wrote the screenplay for the movie Cabiria the same year. Despite his fascist leanings, D’Annunzio did not publicly support the Mussolini regime and tried to persuade him to avoid a pact with Hitler. King Victor Emmanuel III gave him the title of Prince of Montenevoso in 1924, and D’Annunzio became president of the Royal Academy of Italy in 1937.

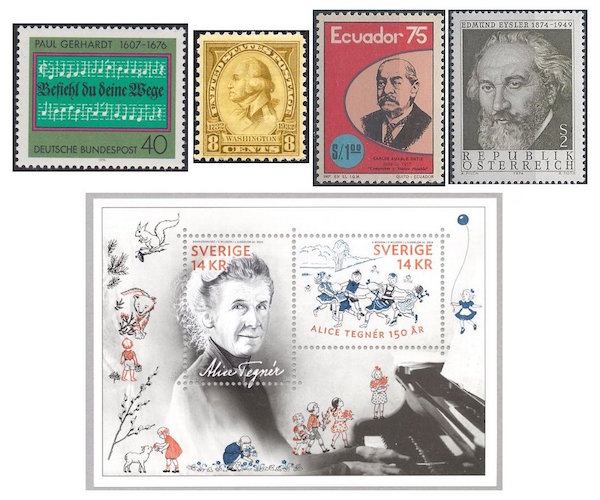

German theologian Paul Gerhardt (12 March 1607 – 27 May 1676) earns a place in the arts as the composer of hymns, some of the melodies of which found their way into compositions by Bach in the next century. Bach used the complete hymn “Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn” as the basis for his cantata of the same name (BWV 92). “Befiehl du deine Wege” (see the stamp) was repeatedly used by Bach in such works as the Saint Matthew Passion (no. 53) and the Cantatas nos. 135 and 153. (Interested parties can find exhaustive information on the subject here.)

French-born engraver Charles de Saint-Mémin (1770 – 23 June 1852) has no stamp of his own, but his work, a portrait of George Washington, can be seen on one of a set of stamps issued for Washington’s bicentenary in 1934. Born and died in Dijon, Saint-Mémin fled the French revolution and turned to engraving in the United States only when he was unable to earn a living doing anything else. Saint-Mémin was not a great artist—he used a device called a physiognotrace to limn silhouettes, but a number of distinguished persons sat for him, including also Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall.

Ecuadorean composer Carlos Amable Ortiz was born in Quito on March 12, 1859. According to the French language Wikipedia article, he attended the first conservatory founded in 1870 in his native town (“Carlos Amable Ortiz fut élève du premier conservatoire de musique fondé en 1870 dans sa ville natale.”), but this must have been a transitory institution, as the current Conservatorio Nacional de Música in Quito appears to have been founded only in 1900. In any case, Ortiz studied violin and piano and was awarded a number of prizes, and President Gabriel García Moreno gave him a scholarship to study at the Milan Conservatory. Unfortunately, the plan could not be realized because of the president’s assassination in 1875. From what I can gather, Ortiz composed mostly songs, though I found a YouTube file of his piano waltz Recuerdo del Conservatorio. For reasons that elude me, he came to be known affectionately as “Pollo” Ortiz, and the YouTube item shows a caricature of him (at about 1:17 in) with the body of a chicken. He died in 1937. A film of his life, called Soñarse muerto after one of his compositions, was made by director Micaela Rueda in 2013.

A very particular niche of the art world was carved out by Alice Tegnér (12 March 1864 – 26 May 1943), but unless you’re Swedish (or you look at the souvenir sheet) you probably wouldn’t guess what it is. Born Alice Sandström, she studied music, became a teacher, and worked as a governess. Her husband Jakob Tegnér became secretary of the Swedish Publishers’ Association, which may have greased the wheels in getting her compositions before the public. Besides classically inspired chamber and sacred music, she put out a book of hymns, Nu ska vi sjunga, that is well known in Sweden, but her main claim to fame is as a writer of many children’s songs, beloved in her homeland. Do you know “Sjung med oss, mamma!“? You have Alice Tegnér to thank for that.

Edmund Samuel Eysler (1874 – 4 October 1949) was an Austrian composer of operetta. As was the case with so many (most?) composers, he was destined for a career in another profession—for Eysler it was to be engineering—but he was drawn to music by his acquaintance Leo Fall (who would also go on to compose operetta) and studied composition at the Vienna Conservatory under Robert Fuchs. He taught piano until a string of successes beginning with Der unsterbliche Lump (The Immortal Blight) in 1910. (He had written a half dozen operettas and one opera before that.) A later work, Der lachende Ehemann (The Laughing Groom, 1913) was performed almost 1800 times in eight years! Now I love the sublime irony of this next bit: Eysler was Hitler’s favorite operetta composer until Der Führer found out that Eysler was Jewish! Boy, was his face red! But by that time Eysler had been given the title of Honored Citizen of Vienna, and he felt secure enough to remain in the city through the war, while his works, of course, were banned. He enjoyed another great success after the war with Wiener Musik (Viennese Music) of 1947, was celebrated by the city on his 75th birthday, and died just six months later.

Two painters round up our survey for today: first, Rita Angus (12 March 1908 – 25 January 1970), a portrait and landscape painter from New Zealand. She studied art extensively without ever taking a degree. Her marriage to Alfred Cook, another artist, did not flourish, but she signed much of her work Rita Cook, later using “R. Mackenzie” (her grandmother’s maiden name) for a time. Her work, inspired by such disparate influences as Byzantine art and Cubism, can be seen in a set of four New Zealand stamps issued in 1983: Island Bay, Central Otago, Wanaka, and Tree, Greymouth.

The other painter, also a sculptor, born exactly seven years after Angus, was Alberto Burri (1915 – 13 February 1995). He was a doctor, specializing in tropical medicine, and as such was sent to Libya upon being drafted in World War II. Captured in Tunisia, he was held as a POW in Texas for two years. There, denied the practice of medicine, he took up painting, using whatever materials came to hand. Thus his later work often was painted on burlap rather than canvas, and he experimented with other substances such as various plastics, adhesives, and fabrics, along with tar, charred wood, and other unconventional media. He met Klee and Miró in Paris in 1949 and soon became one of the prominent Italian artists of the post-war period. His series of what he called “cracked” paintings, or cretti, undertaken from the 1970s, culminated in his covering of most of the town of Gibellina, abandoned after an earthquake, in white concrete. Two of his more conventional abstracts are shown on stamps from France (1992) and Italy (2015).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.