The Arts on the Stamps of the World — March 9

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

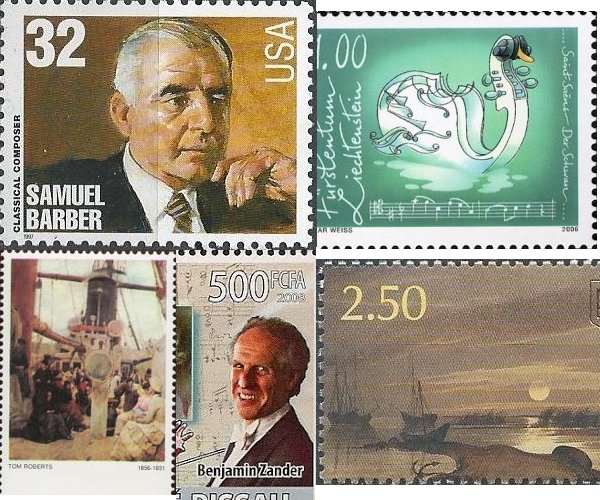

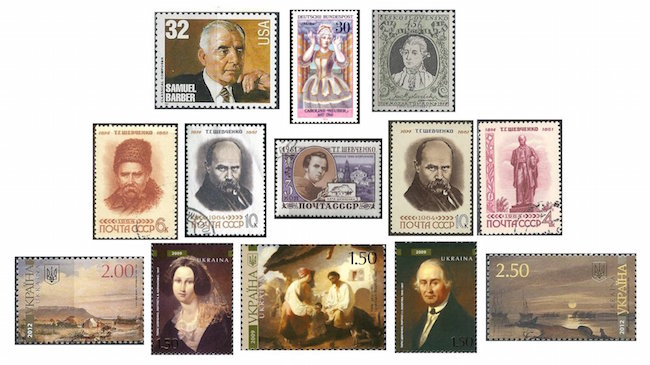

Top place on the Arts on Stamps today goes to one of the finest American composers, Samuel Barber (March 9, 1910 – January 23, 1981), who twice received the Pulitzer Prize for Music: for his opera Vanessa (1956–57) and for his Piano Concerto (1962). Born in Philadelphia, his aunt was the famed Metropolitan Opera contralto Louise Homer. His first composition, written when he was 7, was a 23-bar piano piece in c-minor called Sadness. Barber entered the Curtis Institute at 14 and studied voice with the renowned baritone Emilio de Gogorza. It was while at Curtis that he met his life partner Giancarlo Menotti. His works met with acclaim from his youth until the time of his much criticized opera Antony and Cleopatra, after which he suffered from depression and alcoholism. He also devoted himself to working for musicians and their organizations.

The German actress Caroline Neuber (9 March 1697 – 30 November 1760) was a remarkable force in the theater of her day and one whose influence changed the course of German drama. Born Friederike Caroline Weissenborn in Saxony, she lost her mother at age ten and only escaped the brutality of her father ten years later by eloping with his clerk Johann Neuber. The couple married and set up their own acting troupe. Within a few years they had made a name for themselves, forming a partnership with the critic and drama reformer Johann Christoph Gottsched. Together they worked to improve the quality of German theater by emulating the French and ridding comedy of coarse figures like “Hanswurst”, a buffoonish character that appealed to the canaille. (We could use a woman like Neuber on today’s political scene.) Not only did Neuber impress with her acting ability, but she was one of first women to become the manager of a theatrical company, and she is credited with having “discovered” Gotthold Lessing, who translated French plays for her and wrote his own first play, The Young Scholar, produced by her in 1748. Every two years, as it has done since 1998, the city of Leipzig awards the Caroline Neuber Prize (with €6,000) on her birthday to a woman who has demonstrated excellence in German-language theater arts.

Bohemian composer Josef Mysliveček (1737 – 4 February 1781) was already 24 when he abandoned his father’s lucrative trade as a miller and turned to music. As a person of independent means, he never took employment at a princely court or nobleman’s household, but he was, like Mozart, fiscally irresponsible and died in poverty. He lived in Italy from 1763 and there met the 14-year-old Mozart. One of Wolfgang’s songs, “Ridente la calma”, KV 152 (210a), is based entirely on a melody taken from one of Mysliveček’s operas. In a grotesque accident, an incompetent surgeon burned off Mysliveček’s nose while treating him, probably for syphilis, in 1777. Mysliveček wrote 26 operas, most of which were very successful, oratorios, concertos, some 55 symphonies, and much chamber music, including pioneering works for wind ensemble and string quintet.

A figure who makes me shake my head in wonder was Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (March 9 [O.S. February 25] 1814 – March 10 [O.S. February 26] 1861), a man of keen mind and great gifts who overcame the disadvantages of his birth to achieve distinction, albeit mostly posthumously, in the arts. He was a serf who possessed a natural gift for drawing and somehow attended school and somehow encountered the works of the eighteenth-century philosopher Hryhoriy (Gregory) Skovoroda. As early as 1822 Shevchenko was (somehow) painting horses and soldiers. His mother died in 1824, when he was ten, and his father the next year, whereupon Taras ran away from his guardians in hopes of finding a painting teacher. Three years later he began to work for a nobleman named Engelgardt and after that lord’s death went with his son, Shevchenko’s new master, to Saint Petersburg. There he took up writing poetry. In 1833 he painted a portrait of Engelgardt and assisted as an apprentice in decorating the Bolshoi Theater. Shevchenko met the prominent artist Karl Bryullov, who awarded the young man one of his own paintings as a prize. With the proceeds from the sale of the painting, Shevchenko was able to purchase his freedom, and he began to attend the Imperial Academy of Arts, where he won three silver medals. In the meantime his first book of poetry (1840) was published, to be followed the next year by an epic poem and then plays. He revisited the land of his birth, Ukraine, and saw his relatives, who of course were still living under serfdom. He associated with a liberal society that was suppressed, its members, Shevchenko among them, arrested and sent into exile in the army. With a particularly cruel twist of the knife, Tsar Nicholas I, offended by Shevchenko’s mockery in a poem of the Tsarina, insisted that he not be allowed to write or paint, but these strictures were ignored by Shevchenko’s commander, the naturalist Karl Ernst von Baer, who put Shevchenko’s talents to good use sketching landscapes and nomads around the Aral Sea. Alas, when word of this got back to the higher-ups, the unfortunate Shevchenko was imprisoned in the wretched fortress of Novopetrovsk. Six years in that hellhole ruined his health, and he died, aged 47, one week before the Emancipation of the Serfs. His legacy, though, of both painting and literature, puts him high in the minds of Ukrainians all over the world. Indeed, he is seen as one of the fathers of modern Ukrainian literature (he wrote both in Ukrainian and Russian). Given his Ukrainian nationalism, the Soviets would have suppressed his work, but it was too popular, and many viewed him as a Russian writer, so the authorities downplayed the ethnic strain and emphasized the struggle against the Tsarist monarchy. Among numerous monuments to him are a statue in Washington, D.C., a park in Elmira Heights, New York, and the name of a street in the East Village. As for stamps, he has been honored by both the USSR and independent Ukraine, which released a handome set of reproductions of Shevchenko’s paintings in 2012.

Happily, the life of English-born Australian artist Tom Roberts (1856 – 14 September 1931) is more agreeable in the telling. Born Thomas William Roberts in Dorset, he went at age 13 with his family to Australia, settling near Melbourne and working in a photographer’s studio. After study back in England and travel in Spain and France, where he was introduced to Impressionism, he set up his own studio in Victoria and painted the Australian landscape and scenes of rural life. He is represented on the stamp, however, with his Coming South of 1886.

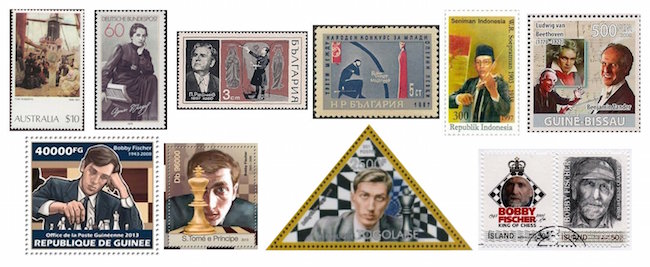

The controversial Agnes Miegel (1879 – 26 October 1964) started writing her poetry in her mid-teens, taught school for a while, and abandoned pursuit of a degree to return home to care for her parents. She received the Kleist Prize in 1916 and was awarded an honorary doctorate from University of Königsberg in 1924. With the appearance of Hitler she became enamored of Nazism and was an enthusiastic supporter of the party, garnering much approval during the Reich. For years after the war, however, the work she produced during that time, including two odes to the Führer, was not included in books of her poems. After a four-year publication ban, she was exonerated by a denazification committee and continued to receive numerous distinctions, her later poetry and stories dealing primarily with the East Prussia of her youth and with loss. Streets and public schools were named for her, and the stamp we see was issued in 1979. In the 1990s the internet made her Nazi associations more public, and some of those streets and all of the schools changed their names, one of them becoming Anne Frank Street. (It should be said that Miegel never demonstrated any tendency to anti-Semitism and was apparently not resentful toward the Russians, writing in a 1951 poem that one should “hate nothing but hate.”) A monument to her in her postwar residence in Bad Nenndorf was removed in 2015, but her house there is still a museum. Should I include her in today’s line-up? I asked myself. Why not just play it safe, delete the stamp image from the collage, save myself some work, and pretend I’d never heard of her (which until a few days ago was true)? I have never read any of her work, which, with all those awards, pre- and post-fascist as well as swastika-smeared, must be at least pretty good. In the end I decided I am not fit to judge, either the work or the woman, and in any case, it’s an instructive story.

Bulgarian tenor Petar Raichev (1887 – 31 August 1960), despite being held in high regard by lovers of the voice, is not well known in the West: his Wikipedia pages are in the Bulgarian and Russian languages only. As a young man he was a cartoonist for local periodicals until the beauty of his voice was recognized, and he was admitted to the Moscow Conservatory after an audition for Ippolitov-Ivanov. He studied further in Naples on a scholarship. He made his debut in 1909 in Sofia and went on to perform throughout Russia until 1920, spending the next fifteen years touring Europe and South America. He also worked as an opera director from as early as 1919. Raichev returned to Bulgaria in 1935/6 and helped to found and direct an opera company in his native town of Varna in 1947. In the last ten years of his life he taught vocal students at the State Academy of Music. His son Ruslan Raychev has made a number of recordings as a conductor.

Raichev’s countryman Konstantin Iliev (1924 – 6 March 1988) was a composer and conductor who studied with Pancho Vladigerov in Sofia and Alois Haba in Prague. In the late 40s he helped in the founding of the Ruse Symphony Orchestra and Ruse Opera. Iliev led the Varna Philharmonic from 1952 to 1956 and then the Sofia Philharmonic, a post he held for nearly 30 years. There is no stamp for Iliev himself, the one we see being one of a pair issued in 1967 on the occasion of the 3rd International Competition for Young Opera Singers and showing a scene from one of Iliev’s two operas, The Master of Boyana (1962). His other works include a ballet, six symphonies, choral works, four string quartets, and music for film and theater. His three books include a biography of Bulgarian composer Lyubomir Pipkov.

Wage Supratman (or Soepratman; 1903 – 17 August 1938) learned guitar and violin and formed a jazz band called Black & White in 1920. Among his songs is “Indonesia Raya,” which has been the national anthem of Indonesia since its independence in 1945. The patriotic language of the song (Supratman also composed the lyrics) led him to be investigated and harassed by Dutch colonial police. He was arrested while suffering from an unspecified illness in 1938 an died in prison days later.

I first met Ben Zander (born March 9, 1939) while working weekends at WCRB, when seasonally a portion of a broadcast day would be given over to a Boston Philharmonic Marathon (fundraiser). Ben founded the orchestra in 1979 and its offshoot, the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, in 2012. Born to German-Jewish parents who fled the Third Reich for Britain in 1937, Zander had the great distinction of studying as a child with his namesake Benjamin Britten and, later, with Imogen Holst. He was himself a member (the youngest, indeed) of a youth orchestra, the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, in which he played cello at age 12. Among his other early teachers was the great Spanish cellist Gaspar Cassadó. He joined the NEC faculty in 1967 and has lived in the Boston area ever since. He has made a number of critically acclaimed recordings, notably a Mahler cycle with the Philharmonia Orchestra for Telarc, and is co-author with his wife Rosamund Stone Zander of the book The Art of Possibility. The tiny West African nation of Guinea-Bissau has been issuing many colorful (and rather pricey) souvenir sheets of composers in recent years. In 2008 the country produced a sheet of four stamps of conductors paired with composers, one of the pairings being our own Ben Zander with Beethoven.

I have long regarded an elegant game of chess as in some respects a carefully crafted work of art, so we honor the eccentric but brilliant Bobby Fischer (1943 – January 17, 2008). He was the eleventh World Chess Champion. The three African stamps are selected from a number of souvenir sheets celebrating his accomplishments. The Icelandic pair represents him in his later years, which he lived in that country. Iceland gave him citizenship so that he could evade deportation to the United States for a variety of violations. Certainly he suffered from some form of personality disorder, but no doubt about it—he was a great genius.

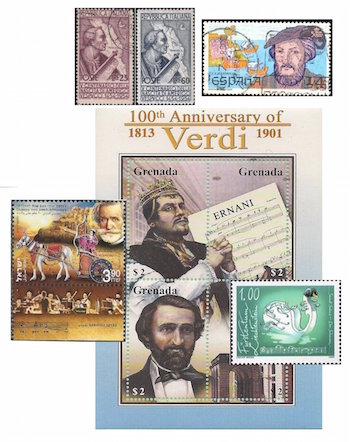

Having paid tribute here recently to an explorer who was a cartographer, as well as to Gerardus Mercator, it would seem churlish to neglect Amerigo Vespucci (1454 – February 22, 1512), who was also a mapmaker. So here is a pair of Italian stamps (in which he is holding a map), along with one from Spain. You may see an irony in the fact that there is no American Amerigo stamp.

Two Verdi operas had their premières on this date: Nabucco at La Scala on 9 March 1842 and Ernani at La Fenice in Venice two years later to the day.

Carnival of the Animals, perhaps the most famous of the works of Camille Saint-Saëns, was written while he was on vacation in Austria and had its first performance at a private concert on this date in 1886, followed by another on April 9th that was attended by Franz Liszt. Saint-Saëns regarded the piece as a slight diversion and allowed only the “Swan” movement, in an arrangement for cello and piano, to be published during his lifetime. It is that movement in particular that is celebrated in this clever 2006 stamp from Liechtenstein, one of a set honoring famous classical compositions. The first public performance of Carnival of the Animals was given on 25 February 1922 by Concerts Colonne in Paris (the composer had died just two months before).

There is some uncertainty about Ornette Coleman’s birthday, with some claiming he was born on March 9, 1930. He just died a year and a half ago on June 11, 2015, and I predict he will have a stamp before long.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse.