The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 10

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

February 10 is the birthday of two great writers, Boris Pasternak and Bertolt Brecht, two great sopranos, Adelina Patti and Maria Cebotari, writers Guillermo Prieto, William Allen White, Joseph Kessel, and Zdeněk Nejedlý, and American actor Lon Chaney Jr. It’s also the 135th anniversary of the first performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Snow Maiden today.

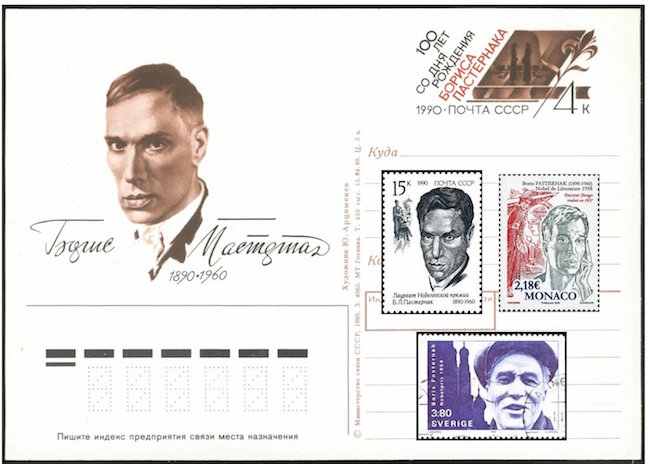

Boris Pasternak ([O.S. 29 January] 1890 – 30 May 1960) might have become a composer. He studied with Scriabin and did write a number of pieces in his youth. (A few of his piano works are available on a Bis CD.) I daresay it’s just as well that he turned to literature instead. In a household that makes one salivate with envy, Pasternak’s painter father and concert pianist mother mingled with the likes of Tolstoy, Rachmaninov, and Rilke. Pasternak began as a poet, which, despite the huge popularity of Doctor Zhivago and his excellence as a translator, was always Pasternak’s métier. The Soviet Union compelled him to decline his Nobel Prize in 1958, humiliated that Zhivago, which had been rejected for publication in the USSR, had achieved such notoriety abroad. With glasnost, the government finally permitted his descendants to accept the Nobel in his name and issued both a stamp and a postal card for him. I display other Pasternak stamps from Monaco and Sweden.

Eugen Bertolt Friedrich Brecht (born 10 February 1898) always went by Eugen as a child. It was only after July 1916 that he styled himself “Bert Brecht” as a theater critic. He escaped dangerous service in World War I only because he wasn’t drafted until the autumn of 1918. That very same year he won the Kleist Prize, a prestigious award for new writers, and just a couple of months later his second play, Drums in the Night, was produced. In that year, 1919, he met Lion Feuchtwanger, with whom he would work in 1924 on an adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II. 1927 brought his first collaboration with Kurt Weill. Their Threepenny Opera of 1928 caused less of a fuss than did their Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, which met with noisy condemnation from Nazis in the audience when it premièred in Leipzig in 1930, but was an unqualified success in Berlin the next year. Brecht fled Germany right after Hitler assumed power in early 1933, moving about Europe and settling in Stockholm for a year before getting his US visa in 1941. He worked on just one Hollywood film script, for Hangmen Also Die!, directed by fellow expat Fritz Lang. An avowed Marxist but never a member of the Communist Party, Brecht was blacklisted and interrogated by the HUAC in 1947 and left for Europe the next day. He died of a heart attack on 14 August 1956.

One of the principal sopranos of the 19th century was Adelina Patti (1843 – 27 September 1919). Born to Italian parents (tenor and soprano) who happened to be working in Madrid at the time, Patti was taken at a young age to New York. Her home in the Bronx still stands. She was already singing professionally as a child and gave her first operatic appearance at 16 in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. Two years later she was invited to Covent Garden, where she made a great success. The stories about Patti are legion. Here are a few. At the height of her career she insisted on being paid $5000 a night, in gold, before the performance. She sang before Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln at the White House in 1862. Verdi declared in 1877 that she was possibly the finest singer who had ever lived, a “stupendous artist.” She became an accomplished billiards player. When she first heard her voice played back on gramophone recordings, she cried, “Maintenant je comprends pourquoi je suis Patti!” (Her first two husbands were French, and she carried a French passport.) And a local one: in 1893, Patti created the title role in a now-forgotten opera called Gabriella by one Emilio Pizzi at its world premiere in Boston. Her final public performance was a Red Cross benefit concert on October 24, 1914 for victims of World War I. She lived long enough to see the Allied victory.

As with Patti, the gods gave Maria Cebotari (1910 – 9 June 1949) a gorgeous voice and a beautiful face, but they allotted Cebotari a life of only 39 years. Her birthplace was the city of Chişinău (pronounced kee-shi-NOW, more or less), and she studied singing at the Conservatory there. Her first operatic performance, as Mimì in La Bohème, took place in Dresden in 1931; then, at the invitation of Bruno Walter, she sang at the Salzburg Festival. She created the role of Aminta in Richard Strauss’ Die schweigsame Frau in 1935. On his recommendation she joined the Berlin State Opera, remaining with them through the war years, then moved on to the Vienna State Opera. Cebotari had a sweet and remarkably versatile voice and was one of the biggest opera stars in Europe. She also worked as an actress in several films, one of them, Odessa in Flames (1942), celebrated Romanian resistance to the Soviet occupation of 1940 and as such was banned and thought to be lost for half a century until a copy was found in the Cinecittà archives in Rome. It was shown for the first time in Romania in 2006. Cebotari’s second husband and the father of her two sons, the Austrian actor Gustav Diessl, died of cardiac arrest in 1948, and she herself succumbed to liver and pancreatic cancer the next year, leaving her two little boys orphaned. With admirable and heartwarming generosity, the great British pianist Clifford Curzon and his wife adopted the children.

Guillermo Prieto Pradillo (1818 – 2 March 1897) was a Mexican writer who served in various capacities (congressional deputy, Minister of Finance, Minister of Foreign Affairs, etc.) in various Liberal Mexican governments. He once saved the life of President Benito Juárez by interceding with rebellious guardsmen. Active from his youth in journalism, at the age of 18 Prieto co-founded an academy to promote Mexican literature. In time he came to be seen by some as Mexico’s national poet. He also taught political economy and national history and wrote novels, short-stories, at least seven plays, and two volumes of memoirs, published in 1906 as Memorias de mis tiempos.

Just a quick word about William Allen White (1868 – January 29, 1944), who was much more significant as a newspaper editor and political figure than as an author, but he did write several novels and short story collections, along with biographies of Woodrow Wilson and Calvin Coolidge. A devoted Progressive, White earned a Pulitzer in 1923 for an editorial he wrote after being arrested standing up for free speech (specifically, this had to do with the Great Railroad Strike of 1922). The United States honored him with a postage stamp four years after his death.

French novelist Joseph Kessel (1898 – 23 July 1979) was born in Argentina and spent his early childhood in Orenburg, Russia before the family moved to France in 1908. He was a flyer in both World Wars. Perhaps his best known work is the novel Belle de Jour (1928), because it was made into a film by Luis Buñuel in 1967. Some of his other writings were also translated to the screen: Le coup de grâce (1931) became Sirocco with Humphrey Bogart in 1951. Kessel was a member of the Académie française and an officer of the Legion of Honor. Since 1991 there has been a Prix Joseph Kessel awarded to books “of a high literary value” written in the French language.

Zdeněk Nejedlý (ZDEN-yek NEH-yed-lee; 1878 – March 9, 1962) was not a nice man. Son of a composer, Nejedlý started out as an opera reviewer for Prague newspapers. In 1903, he published a shot across the bows with his History of Czech Music, in which he condemned the “old” style of Dvořák in favor of the more “modern” Smetana. Not content with promulgating his opinions, Nejedlý set about to destroy the careers of anybody who disagreed with him, attacking composers like Vítězslav Novák and Josef Suk while advocating the music of his friends Josef Bohuslav Foerster and Otakar Ostrčil. He wrote extensively on music, including a biography of Mahler (1913). When the Czechoslovak Communist Party was legalized in 1921, Nejedlý joined at once, fled the country for the USSR during the Nazi occupation, and became Czech Minister of Culture and Education after the war. (His son Vít had died of typhus during the fighting in January 1945). Nejedlý asked to be buried near Smetana, Ostrčil, and his son.

Lon Chaney Jr., born Creighton Tull Chaney on this day in 1906, took the name of his great actor father from 1935. By that time his father, who had discouraged him from an acting career, had died—he never saw any of his son’s work in film. No stamp has honored Lon Chaney Jr. by name, but his face, more or less, appears on one of a group of movie monster stamps issued in 1997. He is seen in his signature role as The Wolf Man. (One of the other stamps depicts his father in his Phantom of the Opera makeup.) Lon Chaney Jr. died of heart failure on July 12, 1973.

The stamp depicting a scene from The Snow Maiden comes from a block of four issued in remembrance of the opera’s composer, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Snow Maiden (Russian: Snegurochka) was first presented on February 10 (O. S. January 29) 1882.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse