Book Review: The Land of Amos Oz

One of Israel’s foremost prose writers has penned a masterful blend of autobiography and invention.

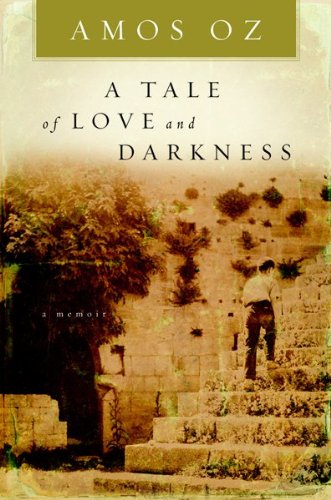

A Tale of Love and Darkness: A Memoir, by Amos Oz. Translated from the Hebrew by Nicholas de Lange. (Harcourt)

By Marsha Pomerantz

In a memoir of 538 pages, it is hard to find a single image emblematic of the whole. But here’s a possibility — Amos Oz imagining his great-uncle Joseph Klausner, renowned historian, native of Lithuania, standing at the edge of his Jerusalem neighborhood in the 1930s, contemplating the Judean Desert:

“On his lips floats a distracted, slightly bewildered smile, as when a man knocks on the door of a house where he is a regular visitor and where he is used to being very warmly received, but when the door opens, a stranger suddenly looks out at him and recoils in surprise, as though asking, ‘Who are you, sir, and why exactly are you here?”

The passage’s combination of anticipated intimacy and actual estrangement runs throughout the three tales interwoven in this memoir: the Hebrew nation returning to its homeland, a man in his sixties connecting the segments of his life before and after his mother’s suicide fifty years earlier, and the writer tangling with the many languages that shaped him and the Hebrew that he shaped in turn.

Oz, one of Israel’s foremost prose writers, is famously seamless of expression, oral and written. In this memoir, he frays and exposes the communal and the personal with insight, humor, pain, and generosity. At the center of the story are Yehuda Arieh Klausner, pale, pedantic, optimistic obsessive; Fania Mussman Klausner, dark, sensitive, imaginative depressive; and their only child Amos, astonishing in potential and burdened with his parents’ unfulfillment. At times Oz throws his voice to relatives and friends, who deliver what might be read as virtuoso arias and recitatives.

Much of the book’s structure is musical, with repetitions, variations on theme and texture, contrasts, and, after much delay, something like a resolution as Oz ventures closer to the trauma of his mother’s death. A bird that seems to chirp the opening notes of Beethoven’s “F?se” appears at a significant moment and accompanies writer and reader intermittently through the rest of the book, most movingly through the suicide scene Oz never witnessed. Some repetitions, however, seem unintentional, as if this memoir was built from a series of shorter reminiscences, and some of the overlappings were overlooked.

The history made vivid here starts with the Eastern European immigrants of the 1920s and 1930s, including the lives they left behind and the dead who pursue them. It goes on to the breathless wait for the 1947 U.N. vote on the partition of Palestine into two states, and the Arab attacks and the siege of Jerusalem that ensued. The featured characters in much of the book are not the Zionist socialists who cultivated the tan-and-muscled “new Jew” on kibbutzim — though Amos himself joined a kibbutz after his mother’s death, when he broke with his father and changed his name to Oz (strength).

For the most part the reader encounters scrawny, belligerent revisionists — shopkeepers, civil servants, and scholars who settled in Jerusalem, reading, writing, and arguing about the meaning of life and the prospects for a state in which they need no longer keep their shirtfronts stain-free so the goyim will think well of them.

Born in Jerusalem, which some of the immigrants find entirely too “Asiatic,” Amos is convinced that by being a polite and pleasant boy (those shirtfronts again) he can demonstrate to Arabs that the influx of Jews is for the greater good of all. Visiting a wealthy Arab family, Amos’s well-intentioned adult companions give their hosts a photo album of life on a kibbutz: pioneers in the fields, naked children under the sprinklers, “and an old Arab peasant, holding fast to his donkey’s halter,” left in the dust by a gigantic kibbutz tractor.

There were geographic, cultural, and emotional abysses to be bridged and the girders of choice were words. Grandpa Alexander “wrote love poems to the Hebrew language, praising its beauty and its musicality, pledging his undying faithfulness — all in Russian.” Oz’s father wrote articles on history and literature, drawing on approximately seventeen languages, and manifestoes against “perfidious Albion,” the British who ruled Palestine, clamping down on Jewish immigration. Then there was the neighbor who, unlike others in the Klausners’ circle, with their reams of “ink-stained index cards,” wrote books “out of his own head.” In fiction young Amos smelled possibility.

Smell is prominent among the book’s many sensualities: synesthesia runs rampant, stones have intricate flavors, and the retractable tape measure the author discovers as a small boy in the dark closet of a women’s dress shop emits “soft puk-puk pulses” that would intrigue any Freudian. The insistence on permeable borders between the senses has a parallel in reciprocity between the animate and the inanimate. As his father points out, in Hebrew the word for “desire” is the same as the word for “object.” Amos wants to be not a writer but a book when he grows up — less vulnerable, more likely to survive. Yet the piles of books in his uncle’s study take on the look of sheep huddled in fright. This mingling of things and beings, so effectively reinvented, seems part of the author’s attempt to reconcile what pulls him apart.

Memoir as reinvention: it can’t be anything else, though questions about verity are tempting. The one chapter that has been excised in the English translation is the author’s tirade against the “bad reader,” who wants to know, after finishing a book, what the real story is. The real story is the inseparability of fact and fiction, and we don’t need that chapter to tell us.

Nicholas de Lange is the longtime translator of Oz’s fiction. His work here is for the most part superb — not easy where flesh and blood is evoked through vernacular, silence, and learned refrains. A few lapses in the English version have to do with the language of everyday life; “a woman who barely came up to [her husband’s] ankles” is the literal rendering of an idiom that’s about character rather than physical stature, and should have been something like “she couldn’t hold a candle to him.”

On the matter of llumination — and verity, and the desert sun’s searching question, “Who are you, sir, and what exactly are you doing here?” — the answers may be found in musings Oz attributes to his mother. “Nobody knows anything about anyone else…,” she says, concluding one of her shadowy tales, “or even about ourselves.” And that’s just as well, “because it’s better to live without knowing than to live in error.” Then she has second thoughts: “Maybe … it’s much easier to live in error than to live in the dark?”