Visual Arts Review: Cartoon Memoirist

By Milo Miles

Iranian expatriate Marjane Satrapi continues to expand the art of the comic book.

Back in the ’40s, the long-standing prejudice that comic books were incapable of presenting serious, adult matters was exploded by such artists as Bernie Krigstein, Harvey Kurtzman, and Will Eisner. But the discovery of how just how uniquely valuable a vehicle comics could be for autobiography was a long time in coming. In fact, it took to the ’70s and Harvey Pekar’s trail-blazing series “American Splendor.” In glorious and grimy detail, Pekar reveled in how Everyman could be a chip off the disaffected block of Dostoveysky’s Underground Man.

But it’s no accident that Pekar’s life and personality reached its fullest expression in the imaginative documentary film version of “American Splendor.”The style of his comic-book autobiography stuck to documentary realism, his plots revolving around carefully crafted characters whose minds and souls fit snugly into the panels.

This straightforward approach is eminently sensible, but it may not be the ideal mode for satiric and/or adventurous autobiography because it leaves out possibilities for a more inventive vision of living in the world. Cartoonist Art Spiegelman caused a pop-culture sensation with “Maus,” which brilliantly tackled the subject of the Holocaust as well as the challenges of living with a difficult parent-survivor. Spiegelman’s drawing style combined German Expressionist woodcuts from the ’20s with Disney funny-animal comics from the ’50s.

The grand master of that more ambitious approach, Carl Barks, argued that, while his stories featured talking ducks, they were far more grounded in harsh reality than, say, superhero fantasies. Spiegelman proved how true this could be, and his finest successor may be a woman who was formed by the impact of another wave of history, the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

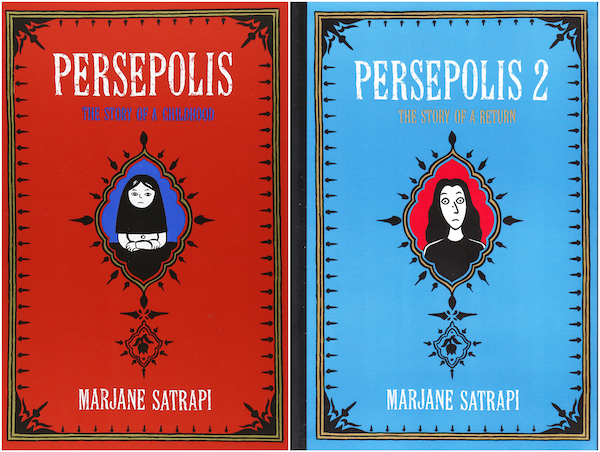

Marjane Satrapi is an Iranian expatriate living in Paris who was primarily known for her children’s books before she published the first volume of her memoir, “Persepolis,” in graphic book form. The child of intellectuals in the Shah’s Iran, Satrapi is informed by the struggle to adapt to a new country as a young adult. As a memoirist, she generates a contradictory art out of blending a kids-book drawing style with the multicultural complexity of her adult sensibility.

Even more than Spiegelman’s woodcut mode, Satrapi’s bare panels zero in on key moments, primary points, and telling faces. Sometimes there are backgrounds, sometimes not. But her panels are never predictable — in their own eccentric way her drawings replicate the lively, shape-shifting of classic Marvel comics. And she provides no fancy graphic moves just for the sake of macho self-aggrandizement. This marriage of the minimal and the maximal lets Satrapi make statements that, even in the context of her small panels, ring loud. In a deft summation of the power of everyday oppression, Satrapi shows herself, veiled, walking outside in post-revolutionary Tehran, filled with fearful thoughts:

“The regime had understood that one person leaving her house while asking herself:

Are my trousers long enough?

Is my veil in place?

Can my make-up be seen?

Are they going to whip me?

No longer asks herself:

Where is my freedom of thought?

Where is my freedom of speech?

What’s going on in the political prisons?

My life, is it livable?”

The “Persepolis” books are the main exhibits of Satrapi’s considerable talents, but anyone who enjoys them should not fail to visit the crucial side-gallery of her new “Embroideries.” Here she takes us into a no-holding-back discussion among Iranian women — including her mother and grandmother — about the nature of sex and the role of females in their lives. Satrapi suggests that frankness and clear thinking is the most subversive theology of them all. In contrast to her plain-speaking drawings, Satrapi weaves together intricate stories that are continually surprising because they don’t conform to Western ideals of feminism or stereotypes about Islamic women.

Mothers and wives of different generations talk about multiple marriages, the joys of being a mistress, faking virginity (the literal sewing-up of the title) and having children without ever seeing a penis. Satrapi is even-handed and endorses neither licentiousness nor fidelity — though seeing the humor in both gets hearty approval. How about nose jobs? Women do them, enjoy them, and worry about them, end of story.

Still, Satrapi insists that people should not believe in things they don’t understand, from “white love-magic” to MTV. She is at her most ferociously incisive when condemning the mindless, ruthless conformity to traditions of female ambition and demureness. The spineless daughter ruled by her grasping mother, the dazzled glamour-aspirant who marries a slick-talking phony — these and others are caught like bugs on pins in Satrapi’s drawings, where they make you smile and sigh.

Perhaps the explanation for her mastery of the graphic form is that Satrapi hasn’t stopped doing children’s books. Like another fearless comic-book memoirist, Julie Doucet, Satrapi is not afraid to appear childish, to portray herself in whatever way the story calls for: foolish, unladylike, mindlessly victimized, enraged, or just plain inexplicable.

What’s more she brings this uninhibited honesty to unmasking our continued belief in the fairy tales we swallowed in our youth. No matter how sophisticated we become, we can never be told often enough that Sleeping Beauty should think about waking up, and that every toad you kiss will not turn into Prince Charming. Satrapi’s brilliance is that that she draws on (as well as draws) the tragicomic realization that everybody, from liberal activists, Islamic revolutionaries, and exiled lovers, will sacrifice all for that happy ending.

Milo Miles has reviewed world-music and American-roots music for “Fresh Air with Terry Gross” since 1989. He is a former music editor of The Boston Phoenix. Milo is a contributing writer for Rolling Stone magazine, and he also written about music for The Village Voice and The New York Times. His blog about pop culture and more is Miles To Go.