Rethinking the Repertoire #6: Felix Mendelssohn’s “Die erste Walpurgisnacht”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the sixth in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

Composer Felix Mendelssohn — Not all sweetness and light.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Sinister, demonic, and subversive are adjectives that might describe plenty of Romantic-era music (especially many of the period’s Faust settings), but they’re probably not the first words to spring to mind if asked to characterize the music of Felix Mendelssohn. No, if anything, Mendelssohn is often viewed as one of two things: the writer of some of the 19th century’s most delicate and pristine music (his incidental score to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, with its spectacularly transparent evocations of Shakespeare’s fairies and their world, is second-to-none just because of that quality) or, in Bernard Shaw’s cutting (and unfair) quip, guilty of “kid-glove gentility…conventional sentimentality and…despicable oratorio-mongering.” But neither view – and especially the latter one – comes close to providing Mendelssohn the composer a full measure of justice. The fact is, Mendelssohn remains one of the West’s most underrated composers, though, since his death, his music and reputation have faced down some pretty long odds.

When he was alive, everything seemed to come easily to him. Born to wealth and privilege, he lacked for little in terms of education and financial support. Mendelssohn’s teenaged triumphs – the brilliant Octet and the extraordinary Overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream – established him as Europe’s most remarkable composer since Mozart and set an almost-impossible bar for his subsequent work to overcome.

And yet the best of his later music, even if it doesn’t surpass those two landmark scores, at least comes awfully close to matching them. His five numbered symphonies succeed to mixed degrees, though the middle three pack a pretty powerful punch and demonstrate as forward-looking a mind as one found in German symphonic music of the 1820s through ‘40s. In the Third, Mendelssohn’s toying with structure – each of its five movements are connected and related, thematically – foreshadowed the work of Schumann, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, and others. The Fourth, perhaps, chronologically, the most popular symphony to turn up in the repertoire between Beethoven’s Ninth and Brahms’ First, follows one of the weirder harmonic schemes of the canon, proceeding from A major (in the first movement) to A minor (in the last).

Mendelssohn’s chamber music – and there is a tremendous amount of it – remains impressive and potent, particularly the E and F minor string quartets, the latter of which was composed over the last months of Mendelssohn’s life in 1847. The eight books of Songs without Words (whose immense popularity seem to have, paradoxically, rendered it something suspect) remain among the most charming, fluid, and idiomatic collections of music for the piano.

And, despite Shaw’s carping to the contrary, Mendelssohn’s two completed oratorios, Paulus and Elijah, offer, between some tedious passages, episodes that thrill as much as much as anything Liszt, Berlioz, or Wagner were composing around the same time. There’s simply nothing despicable about them – unless, like Shaw, you’re an anti-Mendelssohn Wagnerite with a political agenda.

Indeed, after his death from a stroke at thirty-eight, Mendelssohn’s reputation – particularly the fact that he was a converted Jew – was subject to the whims of any number of political agendas. For leading German nationalist thinkers, especially, it became something of punching bag and any discussion of the ebbs and flows of his popularity over the second half of the 19th- and first half of the 20th centuries must take that context into account. It surely helps explain what is perhaps the most notorious posthumous slight Mendelssohn received: inclusion in Richard Wagner’s odious pamphlet Das Judenthum in der Musik (Judaism in Music). In it, Wagner argued that Mendelssohn’s music was “sweet and tinkling [but] without depth,” and demonstrated “that a Jew can possess the richest measure of specific talents, the most refined and varied culture…without even once through all these advantages being able to bring forth in us that profound, heart-and-soul searching effect we expect from music.” These remain shocking words to read – ironic ones, too, considering the inability of the Nazi regime to find a suitable, Aryan-composed replacement for Mendelssohn’s (then-banned) score to A Midsummer Night’s Dream – but they carried plenty of weight for those of a certain era and mindset who were offended or threatened by Mendelssohn’s ancestry. And while such sentiments might be appalling, in this case, at least, they weren’t entirely surprising: in terms of musical philosophy and outlook, Mendelssohn and Wagner were antipodes and Mendelssohn’s essential conservatism made his music, especially during the most radical phase of Wagner’s career as polemicist and composer, anathema to the (slightly) younger man.

Yet the more one digs into Wagner’s kvetch and tries to apply (or understand) his elusive standards, what becomes increasingly apparent is the pathetic mix of unalloyed jealousy and naked insecurity at its root. The fact is, if you want to topple Wagner’s screed and the subsequent arguments it spawned, you needn’t look far into Mendelssohn’s music to do so; in fact, you may as well start with his secular cantata, Die erste Walpurgisnacht (premiered in 1833, but revised and published a decade later), as excellent, profound, and evocative a piece as any he wrote and (it may as well be added) a good deal more focused than anything Wagner composed at or around the same age.

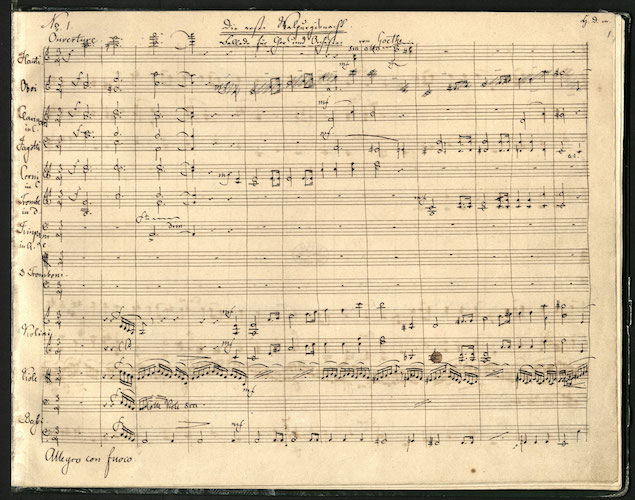

A manuscript page from Felix Mendelssohn’s overture for “Die erste Walpurgisnacht.”

Walpurgisnacht sets a text by that greatest of German Romantic authors, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Mendelssohn met Goethe on three occasions; after their last meeting in 1830, he began setting Goethe’s 1799 ballad that tells of an 8th-century pagan ritual celebrated in the face of Christian oppression. Topically, it’s the antithesis of Mendelssohn’s later big sacred pieces, but thematically, there’s a relationship between all of them, their studies in dualities likely driven by Mendelssohn’s own complex upbringing, part Jewish, part Christian.

For Goethe, too, the poem addressed something of a timeless theme. “The principles on which this poem is based,” he wrote, “are symbolic in the highest sense of the word…in the history of the world, it must…recur that an ancient, tried, established…order of things will be forced aside…and…pent up within the narrowest…limits. The intermediate period, when the opposition of hatred is still possible and practicable, is forcibly represented in this poem, and the flames of a joyful and undisturbed enthusiasm once more blaze high in brilliant light.”

The ballad’s – and Mendelssohn’s cantata’s – approach to these themes, though, isn’t grim or macabre. On the contrary, they’re laced with humor and irony. In terms of plot, the story follows a group of Druids who, banned from celebrating May Day, contrive to scare off their deeply superstitious Christian occupiers by throwing a masquerade in which they dress as devils, demons, and the like. The ruse succeeds, the oppressors (temporarily) flee, and, as the poem and piece end, the Druids are left alone to celebrate their old rituals and the new season in the warmth and light of the sun.

In musical terms, Mendelssohn crafted a score of great subtlety and depth. The music is strikingly moody, seamlessly moving from the storm-tossed turbulence of the Overture to the melancholy lyricism of the opening chorus, “Es lacht die Mai” (which relates the oppression of the Druid traditions). Within its nine movements (excepting the Overture), there’s a remarkable concentration of expression: “Es lacht die Mai” shifts effortlessly from its opening lament to a defiant lighting of sacrificial fires (“Die flamme lodre durch den Rauch”) to a coda of unwavering hope (“So wird das Herz erhoben”) with extraordinary fluency and direction – not a gesture is wasted. You can listen to this opening sequence below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cpap8xkJorY

Mendelssohn’s “elfin” style is often present, but in this context it often sounds more mischievous than ever, as in the chorus “Vertheilt euch hier.” There are echoes of Weber and Berlioz in his scoring – not to mention a neat anticipation of Verdi’s writing for the witches in Macbeth – in the chorus, “Kommt mit Zacken und mit Gabeln,” during which the Druids begin to put their plan into action. Indeed, “Kommt mit Zacken” must rank among the most exciting five minutes or so of music Mendelssohn wrote (and there are quite a few superb five-minute-long selections or excerpts in his output from which to choose).

Walpurgisnacht also packs a hefty dose of irony: the noble chorales given to the Druids and their priest at several points (including in the work’s finale) would not be out of place in Elijah or, especially, Paulus. In fact, this closing touch once provoked an audience member who evidently wasn’t paying close-enough attention to approach Mendelssohn after a performance of the piece and thank him for the “beautiful, redeeming, and elevating Christian chorus at the end” – though, of course, it’s anything but. Now listen from where the previous excerpt leaves off through to the end.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HH_QLJKk3n0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N9guCNkXdQg

So where does all of this leave us? Die erste Walpurgisnacht surely doesn’t reinvent the musical wheel: in terms of form, instrumentation, and harmonic vocabulary, it’s essentially traditional. Yet it’s a piece that, thanks to Mendelssohn’s close identification with the themes of the text and its author, lives and breathes in a special, intense way. If anything, Die erste Walpurgisnacht suggests, to degrees that the oratorios don’t always do, just how potent an opera composer Mendelssohn might have been had he perhaps lived longer. Unlike Elijah or Paulus, which can meander a bit, Walpurgisnacht’s dramatic sense (helped, no doubt, by the directness of Goethe’s verse) is remarkable for its focus. The music, too, with its wide stylistic breadth and total integration with the story it accompanies, is among the finest and most inspired Mendelssohn wrote, fully worthy of comparison with the marvelous Midsummer Night’s Dream score with which it shares not a few similarities. For those reasons alone it ought to be accorded much wider hearing than it’s yet received.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Die erste Walpurgisnacht, Felix Mendelssohn, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Rethinking the Repertoire

A great work. One of Mendelssohn’s finest, I believe.

Choral music in general is performed far too infrequently, particularly since its Romantic heyday. Only now is Schumann’s ‘Paradies und die Peri’ becoming better known and is, in my opinion, the greatest oratorio of the 19th century. Mendelssohn does not suffer alone.

Also, Mendelssohn’s Symphony no. 3 has four movements, not five. (Schumann’s no. 3 has five movements, though.)

A fine and perceptive article. I have a bit of personal history with Die Erste Walpurgisnacht. As a high school sophomore in the early seventies, I was dying to hear a recording of it but there was none available stateside. I was thrilled to locate it finally in Berlin, though it was an inferior performance (Waldman) compared to what has been available since. I excitedly told my local record shop owner (Missoula, MT) of my acquisition, and he said, “Buying from the competition, eh?” I was too young to see what a great, snarky comment that was.

My only disagreement (apart from the five movement error for the Scottish Symphony — Prof. Blumhofer was no doubt casually thinking of the grand coda as an entity) is that I think Elijah moves smartly along in one great arc with no meandering at all! But I do agree that Paulus meanders a bit.

It,s good you are trying to hear Mendelssohn’s music with fresh ears, (and text-reading eyes) but I think you have managed to reinforce the mischaracterization of his music as elfin even while stating it is wrong. If Wagner disliked Mendelssohn, it is because he was hopelessly-indebted to him – many, if not most of the instrumental elements people consider Wagnerian, such as the monumental, martial horn-crested melodies (see movement 1 of M’s 5th symphony) swirling and rising undercurrents (see the piece of music you,re describing here, especially the overture and kommt passage, which the Ride of the Valkyries obviously imitated, and which Mussorgsky clearly-loved) wave motifs like in the Dutchmen (Hebrides overture), etc. can be found in Mendelssohn’s overtures, of which A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an outlier. Consider his Melusine overture – you will even hear “Wagner’s” Rhine motif – and the tail of it “anticipates” W in his more sentimental moods.

(In my humble opinion, only Beethoven was a heavier composer than Felix Mendelssohn)

I would say Mendelssohn’s and Wagner’s reputations are reversed, but Wagner isn’t elfin but sentimental. Most of the storming in W can be found in his bellowing singers and his own megalomaniacal propaganda – extra musical effects. He was politically and polemically radical, for sure, but his music was Mendelssohn’s.

I agree with Shaw’s estimate of M’ s oratorio-mongering as it applies to Paulus, which is very bland like most religious music, and owed much of it’s popularity to a captive religious audience, but if there is a greater piece of choral orchestral music than Elias (without the awful recitative bits, easily skipped) i,m not aware of it.