Dance Review: Revolution in Reverb – Bolshoi Postmodern in HD

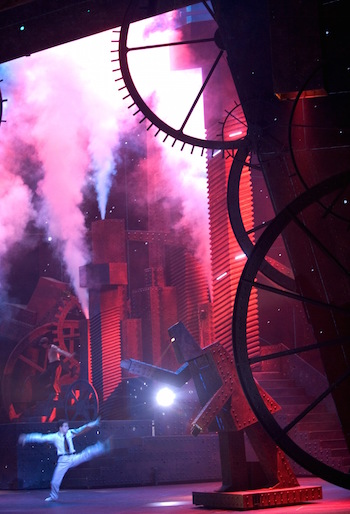

Introduced by gigantic moving set-pieces and robots with prison searchlights for eyes, Bolt often looks like poster art, but Alexei Ratmansky is a smart, subtle choreographer with a gift for double-entendre.

Bolshoi Postmodern: Innovative Performance in HD at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, March 3 through 6. Bolt will be screened on March 5.

A scene from the Bolshoi Ballet production of “Bolt.” Photo: Mikhail Logvinov. Copyright: Bolshoi Theatre.

By Marcia B. Siegel

Bolt, the famous Soviet ballet that never officially opened, was given a 21st century remake in 2005 by Alexei Ratmansky. One of the most important choreographers working today, Ratmansky was then the artistic director of the Bolshoi Ballet, and his production will be shown on a Bel Air recording this week at the Museum of Fine Arts, under the sponsorship of the Ballets Russes Arts Initiative. The film had a preview screening at Boston University on Thursday, preceded by an introductory panel discussion on dance innovation between local choreographers Peter DiMuro, Rebecca Rice, and David Parker, with Katerina Novikova, press secretary to the Bolshoi Theater. Moderator was Dawn Simmons of Boston Center for the Arts, where DiMuro is currently an artist in residence.

Why was Bolt notable if it didn’t get seen after its dress rehearsal? Hard to say. It had a pretty routine score by the young Shostakovich, semi-constructivist choreography by Feodor Lopukhov, and a politically correct libretto by Viktor Smirnov. All three creators incurred the disfavor of the authorities in those days of early Stalinism for their work on Bolt. According to a program essay by Simon Morrison for the DVD (released in 2007), the first Bolt was criticized for being superficial and vulgar. Morrison maintains Lopukhov and Shostakovich intended it as a satire.

All three creators managed some degree of survival after Bolt‘s censure. Lopukhov began as an experimenter who incorporated acrobatic moves and popular social dances into his choreography, but after official disapproval of The Bright Stream in 1935, he was sidetracked into minor companies and a teaching career. Smirnov, the librettist, was a party member who did the party’s bidding in films but quietly wrote ballets until 1945, when he was sent away for making remarks critical of the regime. In a DVD interview, Smirnov’s son maintains that everything had to be coded under the Soviet regime. Treated as a major composer till he died in 1975, Shostakovich was either a successful party hack or a secret dissident. The jury is still out on that.

I don’t know anything about Ratmansky’s politics or how his Bolt was received when it emerged from the troubled Bolshoi ten years ago. He already had an international reputation when he came to the US in 2008, and he’s been remarkably productive ever since; he’s now the resident choreographer of American Ballet Theater.

In some ways, the history of Bolt is a story of protest in disguise. Its real meaning lies underneath the dual abstractions of music and movement. Ramansky’s ballet isn’t meant to be an authentic reconstruction. Even if the actual steps could be recovered, the look and performing style of Bolt depended on the culture of the early Soviet period.

A scene from the Bolshoi Ballet production of “Bolt.” Photo: Mikhail Logvinov. Copyright: Bolshoi Theatre.

Ratmansky’s Bolt follows the original plot outlines, and if Lopukhov and Shostakovich were aiming a criticism at the bureaucratic Soviet state, he’s left that in place. According to recent accounts meant to restore Shostakovich’s reputation, the composer was inserting dissidence into his music as early as this work. Ratmansky has choreographed Shostakovich several times, including The Bright Stream, another Soviet story that’s even more far-fetched than Bolt, and comic in a vaudeville sense.

Bolt‘s plot makes a curious U-turn after the first act. What we take to be the hero, a nonconforming factory worker, gets fired for smoking on the job. During a visit to a disreputable bar, he encounters a street urchin and the two of them dream up the idea of sabotaging the factory. They throw a bolt into the machinery and shut down the works. But the urchin is pressured by the authorities to accuse his former pal. The “hero” is taken away and the urchin is adopted by the hero’s erstwhile girlfriend and her new lover, both of them clean-cut bureaucratic types. The newly established family are then treated to a grand parade of the factory workers.

This synopsis comes from the recording of Ratmansky’s version on DVD; I’m not sure how closely it resembles Smirnov’s. Ratmansky does pick up on Lopukhov’s machine dances and acrobatics. When the factory grinds into action, groups of people clamp together to form slowly revolving wheels that speed up into spinning and running circles. At the beginning of the day the workers, dressed identically in white undershirts and black shorts, line up in rows and do calisthenics as a white-clad individual high above them yells instructions into a megaphone.

One man can’t keep up with the masses and eventually gives up: the hero. The program doesn’t identify him as such, but his timing is off from the start of the exercises; he resumes the pace but does the wrong moves and finally walks off. Later, his drunken solo in the bar is a reckless version of the perfect classical leaps and turns of the good-guy factory worker who gets the girl.

In the culminating Red Army Dances, unison groups stream in representing different branches of the military. Ratmansky’s Defense Workers charge around in gas masks, Aviators are lines of women who swoop past with tilting outstretched arms, and the Cavalry gallop through, as if aiming rifles with one hand and holding imaginary reins with the other.

Introduced by gigantic moving set-pieces and robots with prison searchlights for eyes, Bolt often looks like poster art, but Ratmansky is a smart, subtle choreographer with a gift for double-entendre. He can make movement that expresses character and advances the plot without overthrowing the classical idiom. His humanistic choreography makes the anti-hero and the other main characters sympathetic types. Ratmansky turns the conventional ballet love-scene into an ambiguous struggle. The girl keeps approaching the hero even though she pulls away when he tries to embrace her in a pas de deux. Throughout the ballet, he conveys the idea of the regimented masses versus the individual with strategic use of unison versus solo dances. The contradictions show you there’s more than one story being told.

•••

The other films in this week’s MFA series will include Ratmansky’s remake of the Vasily Vainonen Flames of Paris (1932), a 2010 Bolshoi production of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck, and a performance of Tchaikovsky’s Onegin (the opera) in the Bolshoi production from 2006. Coincidentally, Boston Ballet will be performing John Cranko’s version of the Onegin ballet this week, and it should be fascinating to compare them.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.

Tagged: Alexei Ratmansky, Ballets Russes Arts Initiative., Bolshoi Ballet, Bolt, Feodor Lopukhov, Marcia B. Siegel, Museum of Fine Arts Film