Book Review: Don’t Fear the Cyborg

An engaging new memoir explores how the fusion of man and machine is about maintaining humanity, not creating monsters.

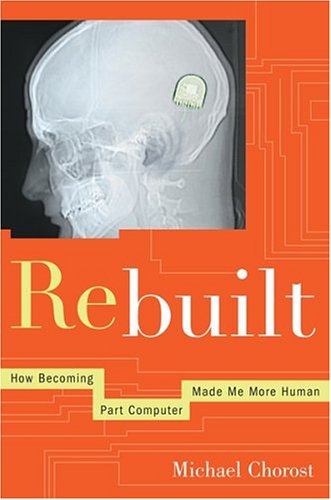

Rebuilt: How Becoming Part Computer Made Me More Human by Michael Chorost. Houghton Mifflin, 240 pages.

By Harvey Blume

Rebuilt is an engaging and entertaining book about our senses and our sense of identity, about sound and silence, and about being digital and remaining human.

The story begins on a day in July, 2001, when Michael Chorost, then 36-years-old, found that his world was being quickly drained of sound. Traffic noises went from their “decisive ‘vrump,’ he wrote, to a whisper. Voices became unintelligible. “Minute by minute,” he scribbled down in panic, “I am going completely deaf.”

To be sure, this wasn’t Chorost’s first brush with deafness. As a young boy he had been a loner who didn’t respond when his parents called him and had only a pint-sized, mispronounced, vocabulary. These symptoms could be explained by retardation, but Chorost’s parents refused to accept that diagnosis for their son. Ignoring one doctor who assured them the boy’s hearing was fine, they consulted an audiologist who found otherwise, and fitted Michael out with a hearing aid.

When, three decades later, deafness struck again, Chorost naturally assumed the hearing aid he was using at the time was at fault. But no amount of tinkering or battery changing helped. He learned soon enough that the problem was now beyond the power of a hearing aid to fix. A hearing aid, he explains, is nothing but a powerful amplifier, transmitting beefed up sound waves to 15,000 tiny hairs in the cochlea, which, in turn, communicate with nerve endings in the brain. Amplification suffices if there are some working hairs in the cochlea, as had been the case when Chorost was a boy. But on that awful day in July, all the hairs in Chorost’s ears were failing for good. The only way he would ever hear again was by accepting a cochlear implant.

Cochlear implants, as Chorost explains them, are fascinating pieces of technology. “For thousands of years,” he writes, “people have dreamed of making the deaf hear. Only in the last twenty-five years,” by means of the implants, “has that become possible and only in the last five has the technology really taken off.” Chorost’s implant consists, first of all, of a microphone that conveys sound waves to a waist-worn microprocessor, which digitizes them and sends the data by wire to a small headpiece on his skull. That headpiece, in turn, radios the data through the bone to another microprocessor — the implant proper — that had been surgically placed inside the skull. Through electrodes, the implant gives the brain the cues it needs to build up sound.

When improvements to the implant are available, more surgery isn’t necessary. Software does the trick. Chorost compares getting implant upgrades to “changing a computer’s operating system from DOS to Windows, or Windows to Linux.” Like anything driven by software, his hearing, he writes, would “always be provisional: the ‘latest’ but never the ‘final’ version.”

Chorost had been a computer geek for much of his life, the kind you might expect to jump at a chance to reroute hearing from fallible wetware to programmable processors. A chip in the head (and one on the belt) are tickets to join the ranks of the fabled cyborgs of our culture — the Six Million Dollar man, for example, Star Trek’s Data, and the Terminator. But Chorost, by the time his hearing gives out, is conscientiously post-geek. Sure, computers have their “pleasures and seductions,” he writes, but he’s discovered that “their remorseless logic” has a serious downside — loneliness and isolation.

Much has been written, since the Internet boom, about geeks and geekdom. Chorost delivers a more up-to-the-minute report: Geeks are looking for something better, more integrated with emotions and other people. In other words, there is life after geekdom. And so, when the time comes, Chorost argues at length with himself about getting a chip in the head, and going the way of the cyborg.

To start with, he hates the definition of cyborg that prevails these days, thanks, in large part, to Arnold and “The Terminator.” He quotes Reese, the good guy from the future in that film, who explains to Sarah that the Arnold monster hunting her is, “microprocessor-controlled, fully armored. Very tough. But outside, it’s living human tissue. Flesh, skin, hair … blood. Grown for the cyborgs.”

No! Chorost all but howls at the movie: “Reese was ‘completely wrong’ in calling the Terminator a cyborg.” The creature played by Arnold was merely a robot, the skin just skin-deep, only a disguise. “Cyborgs,” Chorost insists, “are human beings.” He fine-tunes the definition along the way: Cyborgs are technologically modified, and possibly enhanced human beings. They are hybrid organisms, of a sort, but their humanity is fundamental.

Chorost gets his implant, and proceeds to write a cyber-memoir about life with it. It’s a book that can go rapidly and delightfully from a snippet of the C code used by the device (and the discussion the programmers likely had about it), to a quote from Beethoven about the anguish of being deaf: “For me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversation, no exchange of ideas.”

At its core, this is a book about what we make of the contingency and variability of perception. For example, Chorost has to choose between the software programs available for his implant. Each, he finds, prompts the brain to generate markedly different sound tracks. To his mind, there’s a political lesson in this: There’s no one way of looking at — or listening to — the world. As any real cyborg can tell you, no “unidimensional view of Truth,” can be true.

Listen to a conversation with author Michael Chorost about his book on NPR’s Weekend Edition.

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse, and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.