Arts Remembrance: Peter Matthiessen – The Last Frontiersman

The late writer Peter Matthiessen was one of the last great frontiersmen, one of the last great travelers taking voyages of discovery.

The late Peter Matthiessen — he was preternaturally adept at spotting the many tangled boundaries that ensnare us and endanger the world in which we live.

By Jackson Braider

The French semiologist Roland Barthes, not long before he was run down by a laundry truck on a Paris street in 1980, had been searching for what he called le grain de la voix — “the grain of the voice,” the telltale, often minute inflections that distinguish expression among writers. Barthes may have been speaking metaphorically of the particularities of a writer’s style, but I mention it here because two weeks ago, I woke up to a radio story on NPR’s Weekend Edition Saturday about Peter Matthiessen and his latest book, In Paradise, and the writer was talking.

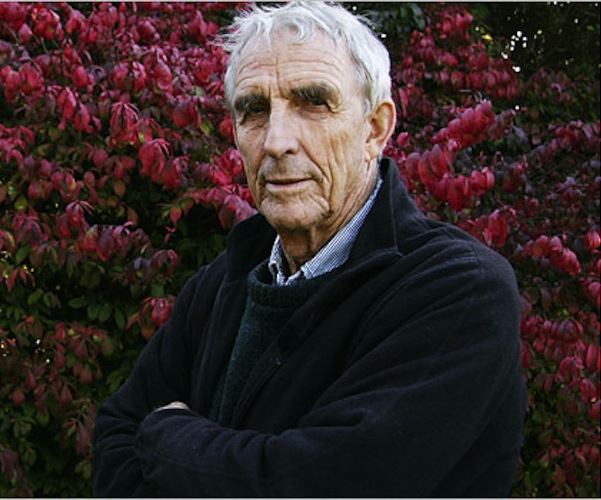

I confess it took me a while to recognize Peter’s voice, though it had been etched in my hearing brain since early childhood. He had, of course, aged in the thirty-some-odd years since I last saw him, but his voice — incisive, always fluid — had remained constant. This past Saturday morning, though, Peter sounded raspy. The reporter noted that Matthiessen had been suffering from cancer recently and was preparing for a new round of chemotherapy. Okay, I thought, that explains the weakness. No doubt he was on the mend.

Which, of course, he wasn’t, as I discovered on The New York Times home page later in the day, after hearing Tom Vitale’s NPR story and then reading the Times magazine interview, all part of the launch for his new novel. Given how much Peter had suddenly occupied my mediascape earlier in the day, I found myself not so much blind-sided or sand-bagged as gobsmacked to read that he’d died.

No doubt there is some literary theory out there that examines how we experience the familiarity of the familiar — Proust and the smell of his madeleines immediately come to mind. Simply hearing Peter that morning on the radio set off a subtle depth charge of recollection and memory, rooted in my family’s past among a community of mid-century artists and writers out on the South Fork of Long Island. Matthiessens and Braiders had been close early on. Luke, Peter’s first son, had been a toddler pal with my brother, Chris; Peter’s first daughter, Sara Carey, was born just days before me; and Peter became my sister Susan’s godfather. We moved away from East Hampton in 1957 and did not see so much of the Matthiessens after that. Still, fifteen years later, Peter could walk into my mother’s kitchen and burst out laughing. “Carol, I would recognize your sink anywhere.” What to say? My mother was never the queen of clean.

The occasion of the visit: Peter had been talking at my school that day, after another one of his adventures — this one involving Great White Sharks off Australia. He had shown us a fairly massive tooth a Great White had lost while attacking the aluminum cage in which Peter and the other divers had sought refuge near the Great Barrier Reef. Murmurs of appreciation rippled among the students.

Peter then reached into his pocket and pulled out another shark’s tooth, this one easily three or four times as large the first. “This came from a Great White Shark perhaps 100 feet long.” Stunned silence. “There is no reason to believe that sharks of such size no longer exist.”

#

What Peter was saying here was a lesson he’d first gleaned from the pages of the great travel, adventure, and nature writers of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, like H.M. Stanley, John Muir, T.E. Lawrence, Laurens van der Post, Richard Francis Burton, and Joseph Conrad. There are worlds not too far from us that defy the so-called brilliant reason of our civilization. No matter how encyclopedic our data and knowledge, how advanced our technology and how painless our modes of travel, we can nonetheless fall off civilization’s edge in but an instant.

In that sense, Peter was one of the last great frontiersmen, one of the last great travelers on the voyages of discovery. His books about his journeys to New Guinea, down the Amazon, across the Himalayas, and into Africa were all reminders that just because we could find these places on maps didn’t mean we had a clue about what was actually there, in them. We learned to appreciate the differences between our world and those thanks largely to Peter’s skills as an observer and writer. Reading volumes such as Under the Mountain Wall and The Cloud Forest would never give us the wherewithal to wander in such places on our own, but, like so much of Peter’s nature writings, these narratives allowed us to glimpse the wondrous, awesome, and sometimes terrifying otherness of these wild places.

And that, I would like to suggest, was just the starting place for the legacy Peter leaves us. As a frontiersman, he had been preternaturally adept at spotting the many tangled boundaries that ensnare us and endanger the world in which we live. As far back as 1959, he was foreseeing the effects of the urban wilderness interface in Wildlife in America. In later books, such as Sal Si Puedes and In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, Peter would trace how Anglo culture, in its growing dissociation from the earth, threatened those peoples who depended upon the soil for their wellbeing and livelihood.

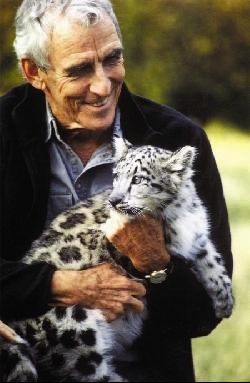

With The Snow Leopard, Peter showed how his expedition into the wider world in search of a near-extinct species of Himalayan mountain cat proved to be a metaphor for the spiritual quest he had begun under the influence of his second wife, Deborah Love. It was the start of a journey from which there would be no egress. It seemed that the farther he ventured away from Deborah during those travels, suffering as she was at the time from terminal cancer, Peter was never getting anywhere close to anything we might characterize as closure.

In the end, closure was probably the last thing Peter was looking for — be it in his journalism, his novels, or even, perhaps, his personal life. A longtime Zenista, he not only confronted contradictions and dichotomies, ambitions and humiliations, pride and foibles, he thrived on them. One of those tag lines that constantly resound in the meditation hall goes something like this: “If I knew of all the karma I would provoke in the world, I would never get up from my cushion.” It’s why the world is filled with hermits and mendicants and crazy people armed to the teeth locked inside bunkers somewhere deep in the Rockies. They all know the damage they could do; that’s why they hide away.

Unlike them, Matthiessen in his life and work chose to get up off the cushion and face the contradictions head on, constantly in pursuit of the unachievable. He wrought much in his 86 years — books and novels, articles, and no doubt poems and prayers as well. Where Christendom soft-talks “eternity” and “the life eternal,” the vocabulary of the Buddhist is, one might say, hell-bent on quantifying existence. There, the talk is of “endless blind passion,” “Dharma gates without number” and a universe of “infinite space” rich in “infinite possibilities.”

So, yeah, Buddhists also appreciate the concept of the eternal; they just devote more effort trying to sum it up. By Peter’s example, while the urge is to resolve conflict and contradiction, we might just try to engage them totally. The title of his last novel says it all: In Paradise. It’s the story of a group of Zen practitioners who decide to hold a retreat in the shadow of a WWII concentration camp. The inspiration for the title comes from a fable about the Buddha, in which the prince, recently escaped from the palace, finds himself in the dankest, dirtiest, plague-ridden ghetto on the planet. Everyone is sick; everyone is miserable; they are all hopeless, they stink to high heaven, and they are all going to die.

Then, suddenly, the Buddha is struck with an insight. “Paradise is here!” he exclaims. “This is Paradise!” And the Buddha bursts out laughing.

Which reminds me of a joke:

The optimist says, “This is the best of all possible worlds.”

The pessimist replies, “I’m afraid you’re right.”

Peter Matthiessen: May 22, 1927 — April 5, 2014

Jackson Braider is an independent radio producer and writer based in Boston. A longtime music journalist, Braider earned his masters in folklore and mythology at UCLA and participated in the New York singer/songwriter scene in the 1980s. He had two songs published in Fast Folk: “The Four Seasons” in 1984 and “Paris by Night” in 1988. Both are available digitally at Smithsonian Folkways.