Classical Music: Harvard Summer Chorus & Orchestras

By Caldwell Titcomb

By Caldwell Titcomb

Harvard’s two main volunteer musical events of the summer took place on consecutive nights in Sanders Theatre. The Summer Chorus, buttressed by a full orchestra, held forth on Friday, July 30, and the Summer School Orchestra followed on Saturday, July 31.

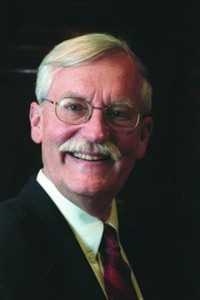

The former was of special significance since the conductor, Jameson Marvin (pictured at left), is retiring this summer after 32 years as Director of Choral Activities and Senior Lecturer on Music at Harvard. For his valedictory Marvin chose to present a program entirely devoted to works by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), the greatest British composer between Handel and Benjamin Britten.

The concert began with “A Choral Flourish” (1956), with the Latin text from Psalm 32, which featured a pair of trumpets and led without break into the grand “O Clap Your Hands” (1920), with English text drawn from Psalm 47, accompanied by a 43-person orchestra. The 97 singers poured forth a properly robust sound.

There followed the gorgeous “Serenade to Music” (1938), which is set to a lengthy stretch of text from the last scene of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. This is a relatively restrained work, with some prominence given the harp, solo violin, and even the triangle. There are occasional brass fanfares, but these are subdued. The excellent vocal soloists were baritone Michael Barrett (an alumnus of Harvard University and Indiana University) and soprano Teresa Wakim (an alumna of Oberlin College and Boston University), who spun a lovely high A.

Concluding the concert were the “Five Mystical Songs” (1911), set to poems by George Herbert (1593-1633). Barrett once again joined the chorus. He did not, however, sing in the final “Antiphon,” in which the full-throated chorus urged “Let all the world in every corner sing.” Certainly every corner of Sanders rang with welcome sound.

The orchestra concert on Saturday was conducted by Judith E. Zuckerman, who has led the group annually for a quarter of a century. The band was 70 strong and ranged from gray-haired adults to a tiny violinist of Asian heritage, who told me he was 12 and had been playing for five years.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), the greatest British composer between Handel and Benjamin Britten.

Zuckerman drew her program from four composers, starting with Jeffrey Brody, who contributed an 11-minute curtain-raiser entitled “Study in Seven” (2009). The title arises from the fact that the piece is consistently written in 7/8 meter. It begins and ends in C-major, though it wanders tonally afield, and culminates in a fugue that stops abruptly. His year of birth was not listed in the program, but when he took a bow he appeared to be in his fifties.

Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) wrote his “Quatre Chansons de Ronsard” in 1941 for the celebrated coloratura soprano Lily Pons. This was the second time he had set poems by Ronsard (1524-85). On this occasion the soprano soloist was Karen Pendleton, an alumna of Wellesley College and the University of Maine. The music called for her to soar to high C, D, and E. In addition, the third number was a real tongue-twister. The fourth was pleasingly jaunty.

Georges Bizet (1838-75) wrote incidental music for Daudet’s play L’Arlésienne in 1872. From this he drew a suite, which proved so popular that after his death his friend and composer Ernest Guiraud fashioned a second suite that remains a part of the regular repertory and was played here. It contains some material drawn from Provençal folksong. The Minuetto has not only a solo for flute but also one for the unusual alto saxophone.

The concert ended with a symphony by Antonin Dvořák. Orchestras frequently program the Seventh, the Eighth, and the Ninth (“New World”). So it was a welcome departure to hear the Sixth in D-Major, Op. 50 (1880). A horn bobble or two were evident, but the players provided an admirable reading and really captured the syncopations in the Scherzo. Zuckerman will doubtless be back on the podium next summer.

Tagged: Caldwell-Titcomb, Classical Music, Jameson Marvin, Ralph Vaughan Williams, The Harvard Summer School Chorus