Fuse News: Elizabethan Genius Gets Its Due — An Edition of Ben Jonson For the Ages

The “Cambridge Jonson” volumes are available online, and the site is a bibliographical joy to behold, Ben Jonson’s plays, poems, masques, and prose arranged in chronological order and in a searchable format.

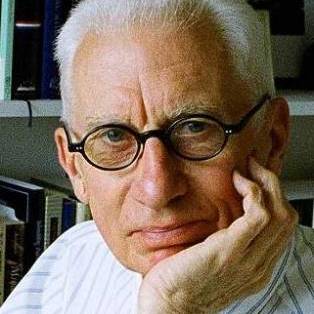

By Bill Marx

In the January 24th issue of the Times Literary Supplement the lead review is of The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson (Seven volumes. Cambridge University Press, $1,050.), David Bevington, Martin Butler, and Ian Donaldson, general editors. In the lengthy piece, critic Brian Vickers concludes that it should be “welcomed as the outstanding edition of any English dramatist in our time.” For those, like myself, who revere Jonson the dramatist (Volpone, The Alchemist, Epicoene, or The Silent Woman) and are convinced that he is a brilliant contemporary of William Shakespeare whose plays has been given short shrift, this herculean, meticulous labor of love, “a masterpiece of logistics and scholarly co-operation,” will invite a long overdue re-consideration among the nonbelievers. Let’s hope that not only scholars and students, but theater directors, drama teachers, actors, and producers wonder what the fuss is all about and take a look at this terrific resource.

You don’t need $1,050 in cash or a library with deep pockets to check out the researched-to-a-T Jonson (the print edition runs to over 5,000 pages). I don’t have a hefty book budget, but I have have been poking, with enormous pleasure, through the Cambridge Jonson volumes. The edition is available online, and it is a joy to behold, Jonson’s copious writings (plays, poems, masques, and prose) arranged in chronological order and in a searchable format. There are detailed considerations of the texts as well as “a series of satellite archives and databases” that will be periodically updated, including “a textual archive with digital images of many of the manuscripts and all of the early printed books from which the edited text is derived, with transcripts of the old-spelling texts and textual essays on each of the works included.” If nothing else, the Cambridge Jonson is a model for “bibliographical standards.”

Of course, the website also sets the scene for a long overdue resurgence of Jonson. Part of the impetus behind Ian Donaldson’s wonderful 2011 biography was to complicate and expand our understanding of the poet and playwright, undercutting stereotypical images of his personality and writings. The tired characterization of Jonson as the hyperventilating scold, obsequious praiser of the upper crust, highbrow brute of a moralist, has obfuscated proper recognition of his remarkable artistry. As Donaldson told me in my interview with him about Ben Jonson: A Life: “Jonson himself is really the big surprise that I hope both the Life and the new Edition will deliver to readers and theatergoers alike. He’s one of the great unknown geniuses of the English theater and of western literature. He deserves to be better known.”

But why should he be better known? I won’t go into detail here, but will offer one reason. In his TLS review, Vickers talks about Jonson’s judgmental vision, indicating that he cultivated a “self-appointed role as judge of human behavior,” taking up a “battle station” in which he declared “I am at feud/ With sin and vice.” I would like to examine that approach, at least when it comes to evaluating Jonson’s achievement as a playwright, because appreciating his exhilarating depiction of ‘sin and vice” on stage suggests why he is particularly relevant today. If he depicted a battle, he gave the enemy plenty of invigoratingly linguistic (and amoral) vim and vigor.

Vickers quotes from Tom Cain’s Cambridge edition introduction to Jonson’s tragedy Sejanus His Fall (a fabulous play that I saw staged by the Royal Shakespeare Company in 2005). Cain argues that the script is “one of the most radical of all early modern plays, an austere dystopian tragedy which displayed the corruption of a successful tyranny without concession to social optimism or religious consolation.” Vickers concludes from this that Jonson is at most successful when he focused on dramatizing vice rather than virtue. And that is where at least some of Jonson’s genius can be found — he disapproved of sin, but in the theater he infused the skullduggery practiced by con men (and women) with a wicked, robustly sung life that attracts as well as repels. His is a satiric view of a proto-capitalist world close to our own, where gargantuan desires blow humane values off the map. His vain and powerful characters, animated by the mechanics of scheming and subterfuge, manipulate others for the sake of accumulating power and prestige, sex and joy toys.

In Jonson’s best plays, big bullies wrestle with little bullies (in Sejanus, big tyrants roughhouse with little tyrants) for the satisfactions of sadistic advantage. Sir Epicure Mammon in The Alchemist prays for a more fantastical imagination because he is impatient with prosaic limits, internal as well as external — he dreams of dreaming of more to desire. The spiritual/moral counterforce to this metaphysical yen for possession and control is suggested rather than concretely present.

Vickers underestimates the merits of Jonson’s early plays, such as the delightful Every Man in His Humor, overlooking their poetic zest because he sees their machinations as rooted in petty villainy, their comically covetous figures wheeling-and-dealing over bling and things. Jonson specialized in depicting — with lyrical/roustabout relish — the dynamism of deceivers self-decieved, the exuberance of fraudulence. Fifty years ago Jan Kott (who would be 100 this year) changed the course of Shakespeare studies when he published Shakespeare Our Contemporary, which connected the Bard with the Absurd. In a burgeoning global shark tank filled with mega-scammers, Madoffs, and billionaire swindlers, the Cambridge Jonson will no doubt help us see that, given our current explosion of unreal estate, Jonson, who erected the first and greatest House of Lies, is our contemporary now.

Note: This year marks the 400th anniversary of the premiere of Jonson’s magnificent comedy Bartholomew Fair, which pits carny folk against puritans. Is anyone out there staging this masterpiece?

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse and a long-time Jonsonian. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.