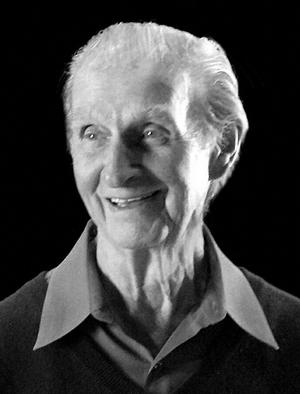

Fuse Dance News: Frederic Franklin — A Legend Passes

Frederic Franklin was the repository of much of the tradition of 20th century ballet, and he carried on these values by personifying the essence of the genre.

By Iris Fanger.

The ballet world lost one of its most beloved legends this week, with the passing of Frederic Franklin at age 98. The British-born dancer graced American stages the country over on his innumerable tours with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo during the ‘30s and ‘40s of the past century. Unlike performers who retreat backstage after their physical prowess has waned, Freddie (as he was universally called), took his bows until nearly the end. He appeared regularly with American Ballet Theatre (ABT) at the company’s spring seasons at Lincoln Center until three years ago in roles as varied as the Friar in Romeo and Juliet, Madge, the witch, in La Sylphide, and the Prince’s tutor in Swan Lake, always an elegant and charismatic figure to watch.

My last glimpse of him was several years ago when I was a guest at an upscale benefit dinner for ABT at the Pierre Hotel in New York. There he was, impeccably dressed in his tuxedo and waltzing around the dance floor with ever-changing partners, each more beautiful than the last. He had earlier made the rounds, table-hopping to greet everyone in his charming, loquacious manner. I was longing for him to ask me to dance, but I had major competition from the company members preening in their party finery.

Born in Liverpool in 1914, Franklin studied ballet at a time when Britain had no ballet companies of its own. He studied tap as well, making his debut in a tap act and later backed up the fabulous, American cabaret star Josephine Baker at the Casino de Paris in Paris in 1931. His skill as a tap dancer was exploited some years after he had joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, under the direction of Leonide Massine. When the company came to New York in 1942, to rehearse its newest work, Rodeo, by the then unknown Agnes de Mille, Franklin was cast as The Champion Roper. He performed a tap dance interlude opposite de Mille, who appeared as The Cowgirl on opening night at the Metropolitan Opera House. Tap dance in a ballet was an innovation at the time.

Ballet Russe was an itinerant troupe that appeared on stages throughout Europe, North and South America, until World War II forced a retreat to performing only in the Americas. The route sheets for the company show the remarkable resilience of the dancers, moving from small town to town, often on one-night stands in an era when traveling was done by train. The dancers would arrive in a community, go to the theater to inspect the often inadequate stage floor and dressing rooms, set up and perform, and hope that a restaurant was open after the show to grab a meal. They would check into a hotel for a few hours of sleep—often four to a room—and be required to wake up early to be at the station to make the train for the next booking. (And that’s not to mention the problems with war-time trains that were requisitioned last minute to carry the troops).

Longer engagements in large cities were a luxury but Ballet Russe, along with the ’20s tours by Anna Pavlova and her company, introduced Americans to the best of ballet and primed audiences for the establishment of the American companies that came later. Franklin also toured with his own company, the Slavenska-Franklin Ballet. One of the works they presented was Valerie Bettis’s Streetcar Named Desire, adapted from the Tennessee Williams play. Franklin, a blond, blue-eyed Brit, cast himself as Stanley Kowalski.

In his later years, Franklin founded the National Ballet of Washington and served as advisor to many other companies. When he staged Giselle for the Dance Theatre of Harlem, he set the work in rural Louisiana, one of the most inspired updates of time and place given a classic I can remember. Franklin also figured prominently in the loving film about aging ballet stars, Ballets Russes, released in 2005.

More than most art forms, ballet depends on the transmission from one generation to the next of material, content, and style. Franklin was the repository of much of the tradition of twentieth-century ballet, and he carried on these values by personifying the essence of the genre. We were lucky to have had him with us for so long.